Musée National Marc Chagall, Nice

16 November 2019 – 27 April 2020

by ANNA McNAY

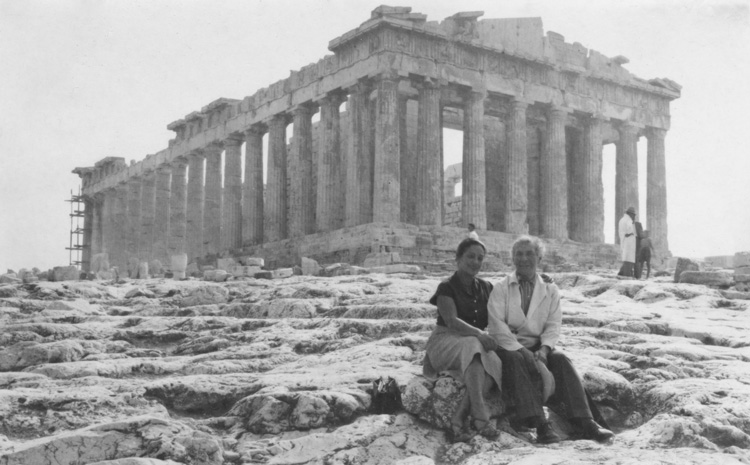

In the early 1950s, Marc Chagall (born 1887, Belarus) accepted the suggestion of his Greek publisher friend Tériade (real name Stratis Eleftheriadis) to illustrate a new edition of the second-century AD pastoral prose romance Daphnis and Chloe, attributed to Longus, and set on the Greek island of Lesbos, where the young shepherd and shepherdess fall in love. To get a feel for the country and its history and mythology, Chagall made two trips there, in 1952 and 1954. He also visited a wider range of tourist destinations, including Athens and Olympia. The Jewish artist was bowled over by what he described as “the land of the gods” – a country where every monument transports the visitor back several thousand years, yet with affinities to the ambience of the French Riviera, where he had made his home in Saint-Paul de Vence. What followed were series of illustrations, not only for Daphnis and Chloe, but also Homer’s Odyssey and Sappho’s poetry, and paintings, gouaches, ceramics and large-scale mosaics (for the faculty of law in Nice), and set and costume designs for the Paris Opera. Hellenic culture became mixed in with Chagall’s Jewish motifs and Old Testament illustrations and remained a prominent influence on his work until his death in 1985.

This delightful temporary exhibition takes over a little more than half of the Musée National Marc Chagall, settled on Cimiez Hill, just above the city of Nice. The purpose-built museum was designed with the artist’s help to house his 17 key biblical paintings, illustrating the books of Genesis, Exodus and the Song of Songs, as well as its later acquisitions of further examples of his religious and spiritual works. While the central rooms with this permanent display of paintings cannot help but outshine the curated Greek explorations, the latter nevertheless manages to shine a light on the artist’s career development and personal interests, which might enable one to then re-view the centrally displayed paintings with further intelligence and deeper understanding and empathy.

[image3]

The first room of the temporary exhibition contains three vitrines, each encasing a vase: Matt White Vase (1952), Black Vase (1956) and The Dream (1952). Chagall’s experimentation with ceramics began around the same time as his travels to Greece, and, rather like his paintings, they comprise a beautiful mishmash of iconography, bringing together figures and motifs from different periods, as well as a majority from his own standard lexicon. The fish on The Dream, for example, is symbolic in part of his hometown of Vitebsk, but also, and here perhaps more specifically, of pleasure, as it escapes the confines of the seas, soaring high into the sky.

The verses of Sappho and other great poets perfectly correlated with the themes already omnipresent in the works of Chagall and, in 1967, he produced a set of 12 lithographs to illustrate his own selection of preferred ancient poetry, capturing a lively vision of the hedonistic and Bacchanalian realm. The following verse from Sappho, for example, is accompanied by an image comprising Chagall’s iconic naked, embracing lovers, lying beneath a (doubtless lascivious) goat, half a crescent moon, a field of grazing sheep and an upside-down bird:

“Blessed husband you have the hymen

that you wanted, and you have the desired virgin.”1

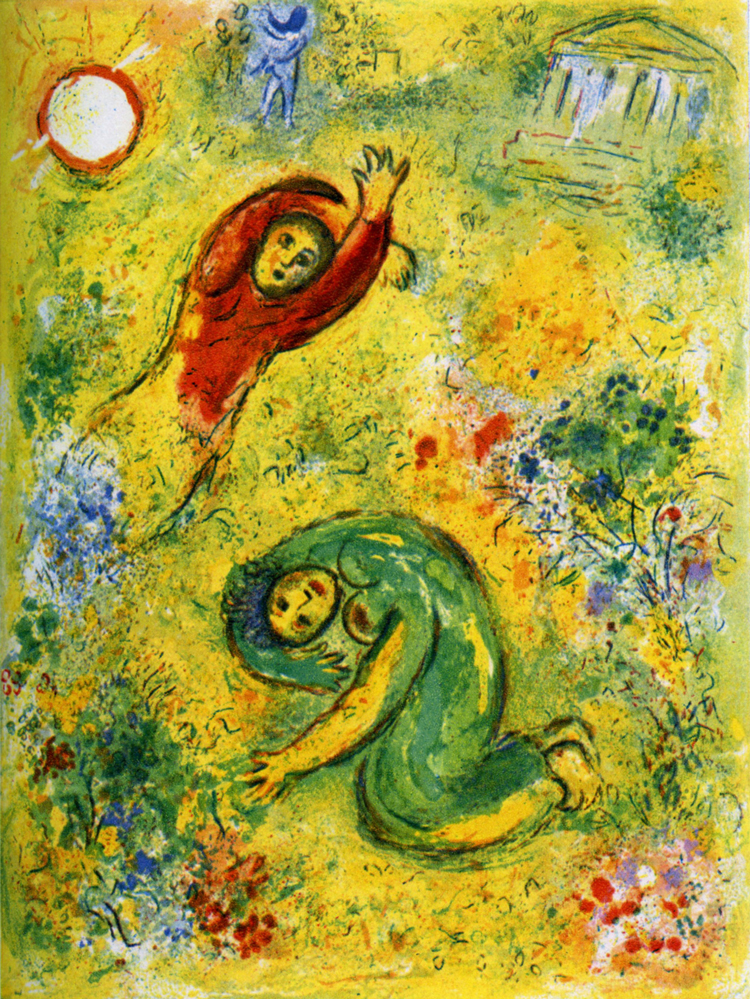

[image2]

Much in Chagall’s work is upturned – fish fly in the sky, cities grow downwards into the earth, animals of all sorts cavort across the page. No wonder the circus was another source of much material for the artist. Since his works were already full of Jewish folklore and fairytale, they were easily adapted, or able to amalgamate, both biblical and, here, Greek mythological and poetical references and symbols. Many of the lithographs illustrating Daphnis and Chloe, for example, could be anywhere in the world – of reality or of dream – were it not for the incorporation of an undeniably Grecian temple facade. As the artist said in an interview in 1952: “Greece is both still Europe but also already the Orient.”2

In the same interview, Chagall also said: “Down there, everything is light.”3 Certainly his emblematic use of primary colours captures the heat and southern Mediterranean luminosity, with the lithographs for Daphnis and Chloe appearing brighter than bright. The complete set of 42 works took the artist four years to finish. Produced in collaboration with the lithographer Charles Sorlier, each plate comprised between 20 and 26 colours, which marked a first in the history of the printmaking technique.

[image4]

While Chagall was working on these lithographs, he was approached by the Paris Opera with a request to simultaneously design the sets and costumes for a new version of the Daphnis and Chloe ballet. The original had been conceived in 1912 by Sergei Diaghilev, to music by Maurice Ravel, with sets and costumes by Léon Bakst, who had tutored Chagall in painting back in St Petersburg. Chagall relished this opportunity to expand the scale of the imagery in his lithographs, ramping up the colour, and bringing his composite of personal dreams and classical mythology to life on the stage. The exhibition has a looped film with entrancing black-and-white footage from backstage at a performance in 1958 and more recent colour footage from the stage itself in 2004, where the splendour of the bright yellow sun over the red valley; or the red moon over the city, inverted on the back of a blue fish; or the yellow lovers and a recalcitrant goat, shine out from the backdrops, before the dancers even enter the stage.

Such is the joy of Chagall’s work – it is vivid and vivacious; full of life, yet full of impossible, enchanted make-believe. As this charming exhibition shows, the “land of the gods”, or of Greek mythology, provided a perfect additional source for him to add to his magical mixing pot of colour and symbolism.

References

1. “Bienheureux époux tu as l’hymen / que tu désirais, et tu possedes la vierge désirée” [trans Anna McNay].

2. “La Grèce c’est encore l’Europe et c’est déjà l’orient.” [trans AMc]. Interview with Jean Dragon in Nice-Matin, 30 October 1952.

3. “Là-bas, tout est lumière” [trans AMc] ibid.