Serpentine Gallery, London

25 November 2006-28 January 2007

A range of symbols spring to mind when thinking about death: the hooded figure wielding a sickle, the faceless boatman ferrying the souls of the dead across the River Styx, the watery existence ascribed to the souls in Hades' underworld and Purgatory - the quintessential departure lounge where Christian souls gather waiting to pass into eternal bliss.

However, death needn't be imagined as the process by which the self is stripped of its fleshy envelope, thereafter existing as an ethereal being. It need not be thought of as exclusively the property of humanity. A change or movement from one state to another, or the destruction of an object in order that its raw material be used for another, quite different object, can also be viewed as a death.

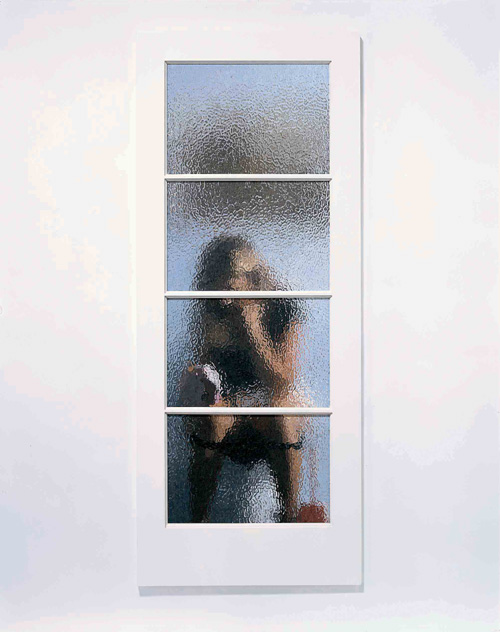

In its many guises, death can be seen as the central feature running through Damien Hirst's murderme collection, which has been recently showing at the Serpentine Gallery. In this show there are works in which the imagery reflects the mythical aspects of death; in others, it reflects the brutal aspect of death, as in the case of Andy Warhol's silkscreen canvases depicting an electric chair and a car crash. The inhumanness of humanity is portrayed by the delicately rendered 'Mechanic' (2006), a work by Tim Lewis, whose images of naked figures, flickering in motion, are seen to be running, one after another, on a treadmill. Some works are downright beautiful, such as Sarah Lucas's piece 'New Religion (blue)' (1999), which consists of lines of blue neon light in the shape of a coffin. Even Jeff Koons's work, 'New Hoover Deluxe Shampoo Polisher' (1980) and 'New Hoover Celebrity IV and Quik Broom' (1980), which are vacuum cleaners attached to light boxes, seem to suggest - by their very inactivity - an absence of life.

It would be wrong to think of this exhibition as being saturnine or serious; it is not. A good many works reveal a humour, however subtle, and it is this that gives the whole show its playfulness. In Nicholas Lumb's piece, 'Skipper' (2006), a pair of battered trainers lying ownerless on the floor is made to appear, by an invisible mechanism, as though they're snouting the ground like hogs.

For me, one of the most evocative pieces is Michael Joo's 'God II' (2003). This is a sculpture of a man, perhaps an Arctic explorer, reclining on his back on a bed of ice. He is frozen. It's this aspect that seems reminiscent of those reports you sometimes read, in which a body is described as being yielded up immaculately preserved by a glacier some 40 or 50 years after that person's disappearance. In the words of WG Sebald, 'And so they are ever returning to us, the dead'.

The exhibition is, indeed, intriguing, not only in terms of the work shown, but also because it reveals much about the collector himself. Hirst's preoccupation with death through the processes of petrifaction, decay, physical transformation and preservation is self-evident to anyone familiar with his work. These interests form the theme throughout this collection. However, there are other qualities that arise: that in death there are aspects of sublimation, delicateness and humour intermingled. It is these aspects, once the cacophony of grotesqueness, the misery of loss and the stench of decay have dissipated, that continue to resonate.

Damien Hirst, with the help of English Heritage, is restoring the Grade I listed building, Toddington Manor, Cheltenham, with the view to housing his own work, along with the murderme collection.

Sophie Arkette