Marlborough, New York

24 January – 11 March 2023

by LILLY WEI

Abstract and representational art converse together amiably, eloquently in this wide-ranging exhibition, the fierce partisanship that once divided them the battles of another generation, as noted by its curator, the New York-based artist Gerard Mossé. Mossé organised the (refreshingly) personal venture in collaboration with Sebastian Sarmiento, Marlborough’s gallery director, one that is a full-throated paean to painting. The curator, as might be deduced, is himself a painter, and the cast of In Search of the Miraculous mirrors his passions. All the works are on canvas, linen, paper, or panel, except for Gisela Colón’s sculpture, which includes an opalescent futuristic urethane column that suggests a totem, made from a (miraculous) list of “cosmic” materials that includes “stardust” and “intergalactic matter.”

[image2]

Its sweep spans the years from c1900 to the present, and offers us an engrossing tour through a momentous, groundbreaking century. As the title tells us, the thread that stitches the show together is an inclination toward the spiritual, but not in espousal of any specific religion. With the death of God proclaimed by Nietzsche in 1882 and the further waning of the formerly pervasive power of the church, one of the main pillars of western European civilisation collapsed. The search for new systems of belief was on. Art, for many, became a locus for spiritual aspirations, offering a less structured, more individual path toward a meaningful existence. The exhibition’s challenging title is taken from PD Ouspensky’s influential 1949 book, and it is a gathering that could include many times the number of artists selected. But Mossé never intended it to be historically comprehensive, and the slightly more than two dozen artists (from several countries in addition to the US) and three dozen works on view seemed to be in the Goldilocks zone: just right.

One of the pleasures of the show is the representation of familiar artists by less familiar works, the surprises adding a stimulating jolt (although that does not mean there is an absence of signature paintings). One less usual work by a usual suspect is also the earliest in the show. It is Piet Mondrian’s roughly textured, autumnally hued trio of chrysanthemums from around 1900, paired with a delicate, slightly later pencil drawing of the extravagantly petalled flower in a more often seen format but still a far cry from the geometric grids that made Mondrian a modernist saint.

[image5]

At the far end of the gallery is a triumvirate of heavy hitters: Ad Reinhardt, Dorothea Rockburne and Agnes Martin. Rockburne’s immaculately folded linen piece, Egyptian Painting: Scribe (1979), is a knockout, suggesting another kind of totem, and forms the centrepiece of what might be viewed as a modern altarpiece. Not far away is a vivacious Infinity-Nets EPB (2011) by Yayoi Kusama, its bright constellated yellow unmistakable, and another linchpin of the exhibition, as is a handsome Adolph Gottlieb, Scale (1946).

[image3]

Richard Pousette-Dart’s colourful, thickly painted Window, Cathedral (c1941-1942) is also notable, an impressionistic surface structured into a kind of bas-relief, its material facticity alternating with its optical complexities. Near it is a striking Olafur Eliasson painting based on the spectrum, another variation on the phenomenology of light and colour.

Not all the works are abstract, as mentioned. There is a Charles Burchfield landscape, a watercolour from 1946, its flora scintillating with mystical vibrations; a jazzy, boldly coloured, New York City street scene alive with the spirit of place by Beauford Delaney, channelling American modernists such as Stuart Davis and Arthur Dove, who is also in the show; and a captivating Giorgio Morandi painting that is less serene than it appears at first, its brushwork subtly roiled, overriding the stasis of his not-so-still life.

[image6]

Another great pleasure of the show are the works by the less canonical artists. Mossé is represented by a richly hued painting – colour and light, both physically and metaphysically, his longtime subjects – and a tonal black-and-white drawing of similar imagery. The figures in each are tautly opposed, haloed totems that radiate their own inner luminosity, as if plugged directly into a source of cosmic energy. Other works include a painting by James Biederman, a reverberant, eye-catching landscape/mindscape and a series of Roland Flexner’s signature automatic drawings of liquid graphite that resolve into, say, galactic worlds and other fantastic realms.

[image4]

Nancy Haynes’ two exquisitely nuanced abstractions are titled Sixth Arrondissement (2015) and This Painting (2015), her projects often spurred by – and inextricably linked to – literary references. Here, they summon up Jean-Paul Sartre’s Paris and the nature of being and non-being, as she, uncannily, transubstantiates material into metaphor. Yulia Pinkusevich, the youngest artist in the show, conjures the Sakha Air Spirit (2021). A haunting, ethereal pink and grey pastel and charcoal drawing, it is slightly over 6ft (1.8 metres) tall and pierced by a brilliant star blazing near the top, one of a series that explores the Siberian shamanistic rituals of her maternal family.

[image7]

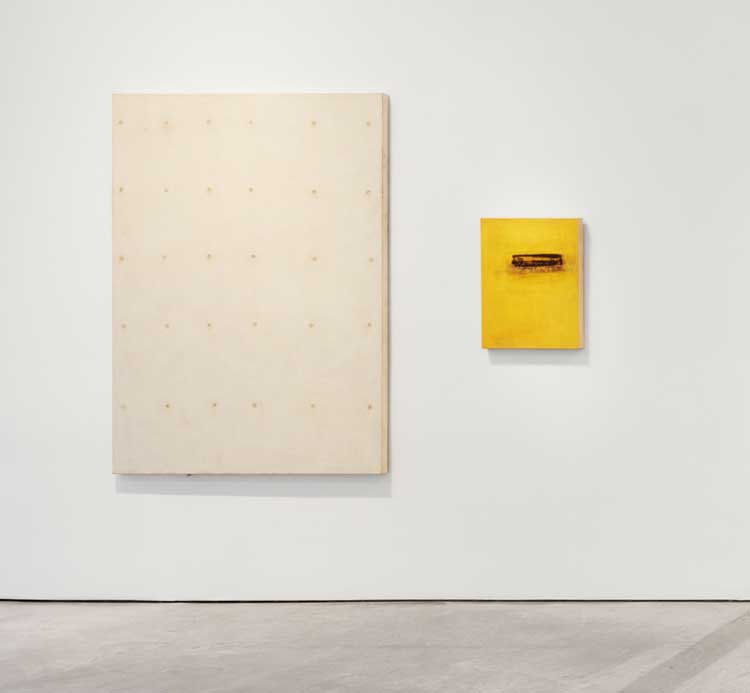

At the entrance to the exhibition there are two paintings by Denzil Hurley, a Seattle-based artist who died in 2021. The small work is a glowing yellow while the large one is deep cream. Both might be called minimalist, their narratives formal, but personalised by the sensitivity of his touch. The tiny brownish circles in the larger canvas, for instance, march across it in rows of six across, five down, orderly, but slightly irregularly, as evidence of his hand, his presence.

The search, here, is for miracles on many levels, from those of painting to art itself. It is an homage to the most venerable and protean of mediums and to artists who paint. Painting’s allure has endured across millennia and has translated the world for us from our beginnings, both the world outside of ourselves and the ones we hold in our heads and hearts. Mossé reminds us that art is essential to our humanity, and that painting is one transcendent, incomparable expression of it.

![Left to right: Olafur Eliasson, Colour experiment no. 29 (light spectrum), 2010, oil on canvas, 78 5/8 × 79 × 2 3/4 in (199.7 × 200.7 × 7 cm); Yayoi Kusama, Infinity-Nets [EBP], 2011, acrylic on canvas, 63 3/4 × 63 1/2 in (161.9 × 161.3 cm); Gerard Mossé, From My Head Down To My Shoes, 2019-21, oil on linen, 56 × 42 in (142.2 × 106.7 cm); Untitled, 2020-21, charcoal, graphite, and pastel on paper, 17 × 7 7/8 in (43.2 × 20 cm). Installation view, Marlborough Gallery, New York. Photo: Olympia Shannon.](/images/articles/i/081-In-Search-of-the-Miraculous-2023/In-Search-of-the-Miraculous,-2023,-View-7_Olympia-Shannon.jpg)