by ALLIE BISWAS

Born in 1966 in Mezaligon, in what was then known as Burma and was renamed Myanmar in 1989, Htein Lin is a painter, installation and performance artist who has also worked as a comedian and actor. From 1962 to 2011, the country was ruled by a military junta and Lin was jailed from 1998 to 2004 for challenging the dictatorship. During his time as a political prisoner, he used what he could get hold of – such as bars of soap, cigarette lighters and prison uniforms – to make paintings and sculptures. Following his imprisonment, he left to live in London in 2006, finally returning to Myanmar in 2012.

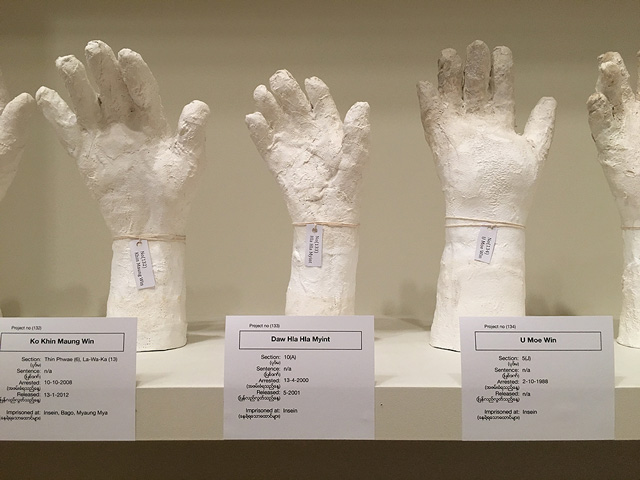

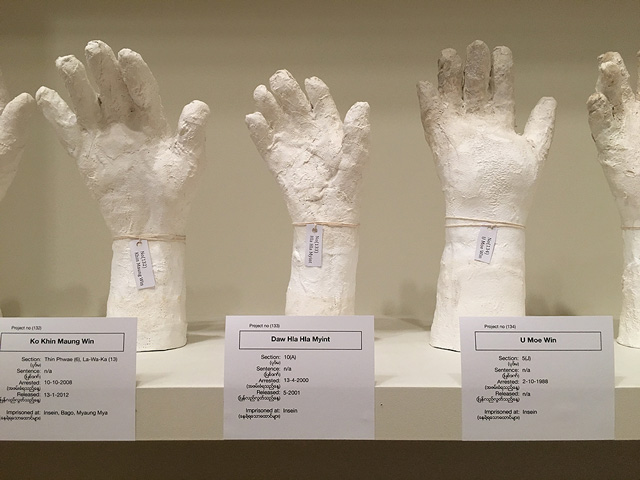

After a bike accident in London that resulted in a broken arm, Lin was inspired to think about the qualities of plaster and, in 2013, began work on his large-scale installation A Show of Hands. Connecting the material to his experiences of imprisonment for his pro-democracy activism, Lin began plastering the arms of former political prisoners, honouring their stories through these sculptural replicas. A Show of Hands premiered at Lin’s 2015 exhibition The Storyteller, at the Goethe Villa in Yangon, which also included some of his prison paintings, detailing personal narratives of being in jail. The installation has now been brought to the US, opening this month at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Bufflao, New York. The work includes hundreds of plaster sculptures cast from the hands of former Burmese political prisoners, each accompanied by a card bearing information about the circumstances of the individual’s imprisonment. As part of this iteration at Albright-Knox, Lin will also cast the hands of former Burmese political prisoners who live in the local area around the museum.

[image3]

Allie Biswas: Can you tell me about the start of your interest in art?

Htein Lin: From the age of about 12, I began drawing for my schoolfriends – pictures of village life and illustrations for their schoolbooks.

AB: I understand that the theatre became a turning point for you later on.

HL: My father would let me see the movies that came to the village and I would help my friend change the film reels. Then, when I went to Rangoon University [now the University of Yangon] to study law, I became involved in a student comedy group. We performed a-nyeint, which is a traditional form of Myanmar performance and consists of four young men doing slapstick comedy and satire, and a female dancer. Our troupe was coached by Zargana, who was a few years older than us and had become a famous comedian who told political jokes against the military dictatorship.

AB: What impact did your experience of being imprisoned have on your art?

HL: My university education was interrupted by the 1988 pro-democracy demonstrations, of which I was a leader in my village. I then had to flee to a refugee camp on the Indian border, and subsequently to one on the Chinese border, where I and a group of my friends were imprisoned by other student rebels. We were tortured and some of the group were executed. In India, I was taught by the famous Mandalay artist Sitt Nyein Aye how to draw on the rationed paper we received, and I drew, too, on newspaper and in the mud. While trekking through the jungle, I also drew in mud, and when imprisoned in the student camp for seven months in 1991-92, I would draw, sometimes under duress. I would also sing and tell jokes for my fellow student prisoners. So, even before I went to prison in 1998, I was used to making art and performing in whatever situations and with whatever implements were available.

AB: Can you tell me about your experience of making art within this very specific context – prison? Was it a collaborative experience, involving other prisoners, or something more private?

HL: I was imprisoned from 1998 to 2004. I made art for myself, but also for my fellow prisoners. Mostly, I did paintings on cotton prison uniforms using found objects such as lids from toothpaste tubes and fishing nets that the guards would bring me, along with paint I would persuade them to smuggle in. Sometimes, I would do drawings on paper. We would also collaborate and put on performances occasionally. We had to hide all our materials and find guards who were sympathetic and would smuggle them out. We would also produce our own samizdat – single-issue books of poetry and essays – passing them around to contribute to and read, and I would illustrate these. I started painting because I was hearing news from my fellow artists outside jail that they were still working and had their own exhibitions. I wanted to show them that I could also continue to create.

[image4]

AB: From 2006 to 2012, you were in exile in London. What impact did life in London have on your work? The installation at Albright Knox, A Show of Hands, was initiated after you returned home to Myanmar in 2013. What was the starting point for this project? And was your homecoming a big motivation in terms of the work's inception?

HL: I wasn’t really in exile – I left Myanmar in 2006 to join my wife in London. But I might not have been safe if I had gone back to Myanmar after that, because there were lots of political events going on in which I would have participated, such as the Saffron revolution in 2007. Lots of political prisoner friends of mine who were released with me in 2004 were taken back inside during the Saffron revolution.

In London, I had access to more materials, and more inspiration as well as art education, as I was able to visit art galleries such as Tate Modern – my favourite. I used my art, both painting and performance, to draw attention to events in Myanmar such as the Saffron revolution, Cyclone Nargis [in 2008, the cyclone caused the worst natural disaster in Burma’s history], the 2008 referendum, the 2010 general election, and the 2011 Myitsone dam issue.

AB: And your interest in plaster arose from a specific incident?

HL: While I was in London, I had a bicycle accident and broke my arm, which was put in plaster. That inspired me to learn more about plaster of paris and experiment with it on my Burmese friends. It was through that that I began the project A Show of Hands, plastering the arms of former political prisoners outside Myanmar and collecting their stories, and then continuing once I returned on my first visit back in 2012, and again when I finally moved back in 2013.

AB: The work has sculptural and performative qualities.

HL: Yes, A Show of Hands is a sculpture and a public performance project. It is a public act, as the prisoners often use it as an opportunity to reminisce. Also, when I make the plaster hands in a public place, it interests the younger generation who do not know exactly how much the older generation sacrificed. I also learn a lot from talking to the prisoners, including the challenges faced in the women’s jails which previously I wasn’t aware of.

AB: Part of your exhibition involves casting new hands – those of former Burmese political prisoners in the region around the museum. What has been the process of finding these participants, and what do you think these new additions – these new casts – bring to the installation?

HL: Unfortunately, A Show of Hands is a project that never ends. There are so many former political prisoners, but, even now, our supposedly democratic government is creating new ones. I would like everyone’s story and their sacrifice to be recorded. That is why, whether I travel in Myanmar or outside to places where there is a large Myanmar community, I put the word out through social media and personal networks that I would like to meet and plaster the right arms of any former political prisoners who are interested. I want to ensure that their stories are remembered.

AB: What gesture are you hoping to make by including these local people?

HL: It is important that no one’s sacrifice should be forgotten and that the next generation should know what their parents experienced.

AB: How has your art developed since making Myanmar your home again, over the past few years?

Since I moved back in 2013, in addition to continuing A Show of Hands, I have embarked on some new painting and installation series, many of which are inspired by the changes taking place in Myanmar, not all of them positive, and also by some traditional beliefs that are still in place. One of these changes is the switch from bullock-drawn carts to mechanised transport. I have collected old bullock-cart wheels and transformed them into useful objects, such as beds and chairs, and thoughtful objects that recall the symbol of the wheel in Buddhism. In my series Signs of the Times, I have also collected the offcuts of vinyl signboards, which leave a random collection of cut-out letters, and created new images and messages that show the nature of change in Myanmar. With my Recycled series, which I began shortly after my release in 2005, when I could not afford paper or canvas, only locally recycled card, I am now capturing Myanmar words and events, such as the assassination in 2017 of Muslim lawyer Ko Ni, and the controversial word Rohingya, and the revival of the dispute around the Myitsone dam. Since Myanmar has its own alphabet, these paintings are effectively coded, so that an international audience will not understand unless the word is explained to them. I have also commented on the destruction and burning of villages in ethnic areas in my installation Recently Departed, which was shown in Yangon in January this year.

My current major series is called Skirting the Issue. It invites Myanmar women to comment on the traditional belief that a man’s “hpone” or masculinity will be weakened through contact with women’s clothing. I invite women to bring me their old longyis (skirts) and I paint their portrait on the longyi and they comment on their views on this belief and whether they support it or not. Many still do, but some do not, and believe it underpins some of the ongoing discrimination against women in Myanmar.

AB: Are your memories of the country as it previously was, and your experience of imprisonment, very much still within your vision?

HL: I have always been able to adapt to any situation, whether it be a jungle, a refugee camp, a prison or somewhere abroad. I am not haunted by my prison time – it was very much an inspiration for me, and also saved my life. When I was released after six and a half years, I found that many of my artist and actor friends had become ill. I was healthy and able to meditate.

AB: Finally, what is the arts culture within Myanmar developing today? Are you part of a community of artists?

HL: There is a strong arts scene, much of which is supported by foreign galleries and cultural institutions such as the Goethe Institute, the Japan Foundation and Alliance Française, as well as some private-sector sponsorship, including support from large Myanmar companies. The Myanmar government does not give any real financial support to contemporary or conceptual art, and very little moral support either. It is difficult to get the National Museum interested in anything modern.

However, I am lucky that I shared a cell for three years with Phyo Min Thein, who is now the chief minister of Yangon, and he is supportive of the projects I have been involved in. These include the My Yangon, My Home festival, which we held in 2015 and 2017. This was a multisite, multimedia exhibition throughout Yangon, including a wire sculpture on a commuter bus, a sound installation in a teashop and a photo exhibition on an overpass from the docks. I am always keen to bring art out into the public space, something I saw while in Europe, but which is not yet well established in Myanmar. The chief minister shares this ambition.

In addition to the support of the Goethe Institute, which has organised many artistic events, I have also collaborated a lot with the Pyinsa Rasa art group, which was able to put on a number of art events in the old secretariat building, a historic space and former colonial ministerial office building in which Aung San, Burma’s independence hero, was assassinated in 1947. In July 2018, I curated a group show called Seven Decades, in which Myanmar artists of different ages developed new pieces that identified with one of the decades of post-independence Myanmar.

• Htein Lin: A Show of Hands is at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, until 28 April 2019.