by JANET McKENZIE

British artist Hilarie Mais (b1952) grew up in Leeds and trained at the Winchester School of Art and the Slade where she was taught by Malcolm Hughes, Tess Jaray and Sir Lawrence Gowing. She visited New York on travelling scholarships from 1973 and was offered her first solo exhibition at Cunningham Ward Gallery, New York, in 1977, while still a student, before taking up a fellowship at the New York Studio School where she stayed for five years. By the time she arrived in Sydney in 1981 with her husband, William Wright, the director of the 1982 Sydney Biennale, she brought with her a wealth of experience absorbed from the New York art scene.

Mais makes abstract constructions that can be positioned somewhere between sculpture and painting. She merges the formal structure of the grid – her starting point – with organic forms from nature. D’Arcy Thompson’s On Growth and Form, which had a revival of interest in the early 1970s, was one of many influences on her work. Although conceived within a geometric space and informed by minimalism, Mais’s working methods and the final pieces are informed by personal narrative and are emotionally charged and enigmatic.

[image4]

Anthony Bond, in his essay to accompany the 2017 solo exhibition Hilarie Mais, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, observes the importance of the relationship between the investment an artist makes in the object, the material and the process – and the investment that comes from a very personal space, quoting Mais: “My work frequently contains the element of the autobiographical. It is often the emotional starting point of the work and through the working and engagement and dialogue, the work becomes autonomous, it becomes itself.”

At Winchester School of Art, Mais says, the emphasis on drawing from life, “nine to five, five days a week”, set in place the capacity to think visually and, as a sculptor, she continues to draw with wooden pieces on to the ground. She has said: “Drawing is such a fundamental basis of visual articulation and I cannot imagine the thought processes involved without the ability to relate perceptually; to analyse, to form, measure, create and revise both relative scale and position, to conceive and develop one’s conception by means of drawing.”1 The New York Studio School was founded with the rigorous teaching of drawing as the core and it attracted international artists of stature. Mais has exhibited widely in Australia and internationally.

Janet McKenzie: New York in the 1970s must have been a momentous experience, with the works of Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt, and the ideology of feminism?

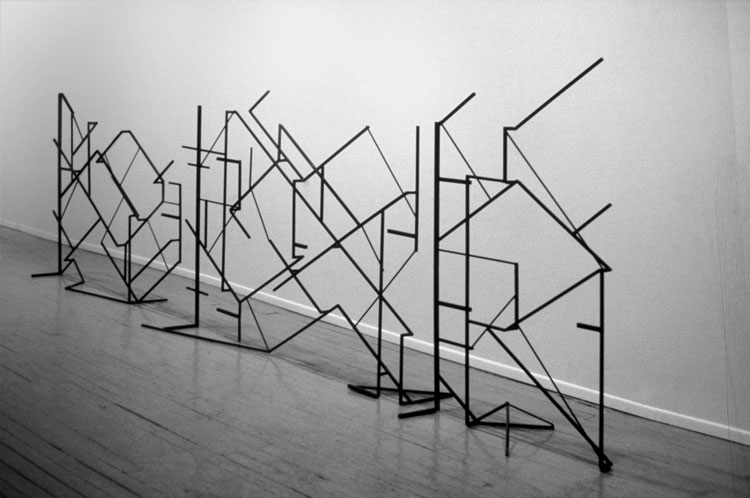

Hilarie Mais: The early 70s was a time of huge social upheaval. I was living in London during the recession, the three-day week, blackouts, unemployment and punk music and, in the midst of this, was the burgeoning presence of feminism. I had been travelling back and forth between London and New York since 1973, and I continue do so from Sydney. Both art worlds were vibrant and potent, and finally moving to New York was like stepping into a history book, with first-hand connections with abstract expressionism, minimalism, the Parthenon of modern American art history. Feminism unleashed, liberated and activated a space for the female voice. The vocabulary that evolved was in response to social observation and critique, self-reflection and the personal as political. It identified a space from which to deal with the issues of female gender. I previously had thought of myself as almost a nongender artist using the male-dominated vocabulary of formalism. It was considered at the time that the materials you used carried a gendered presence, I was working with steel, which was considered inappropriate although. At this time, I produced my Weapon series in steel, but with a strong female content, with reference to the violence embedded within society and the domestic life of women.

[image3]

JMcK: What did your five-year fellowship at the New York Studio School teach you about being an artist?

HM: I was already an exhibiting artist when I joined the New York Studio School (NYSS). I was there on a travel scholarship from the Slade for one year and then continued to work there after being awarded a further scholarship with NYSS and a visiting artist studio at Purchase College, State University of New York. I guess I matured as an artist there. What the NYSS gave me was a community with other artists working in Manhattan: the support, the network, access to workshops and amazing tutors and lecturers. It was an intense, privileged immersion into the New York art world. I loved living there. It was in the days of huge, cheap, illegal loft living, galleries just starting to populate SoHo and Greenwich village, access to numerous museums and, of course, the vibrancy of inner-city life.

JMcK: You began to draw in steel at the New York Studio School. How important is your choice of material – wood or steel?

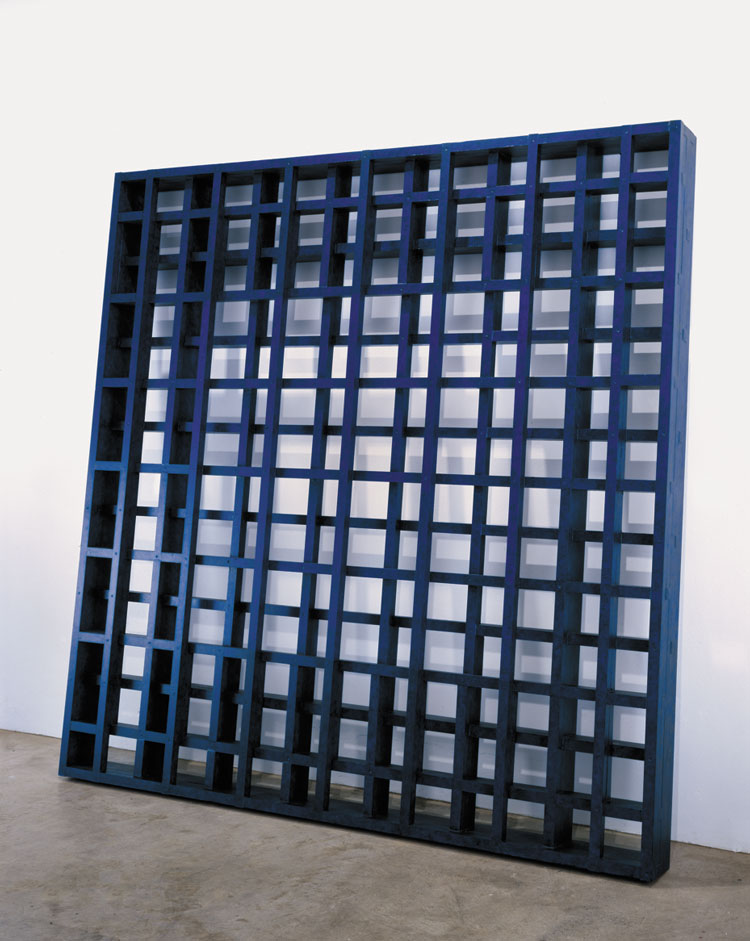

HM: Actually, I had been drawing with steel for a long while. My early practice developed around formal concerns of attempting to draw in space, articulate space with line, which then went on to involve my interest in colour as line and density. Steel is the perfect material for a direct, spontaneous way of working, the immediacy of welding, the flexibility of steel, its tensile quality to span space while working against the floor as if drawing on a wall. I now work with wood, which was a decision based around the weight and scale I was wanting to work with, my approximate body size and span being approximately six-foot square; I work alone without studio assistants, so wood became my preferred material. The works often lean against the wall, the structural presence occupying and claiming the physical space and relationship with the audience. Grid V is an example.

[image9]

The work is not fabricated; I make it myself, which is pivotal in terms of decision-making. I make no preparatory drawings; hence I am drawing with material. The intense involvement with the structural process enables decisions and responses in the evolution of a work. I continue to work with wood and, after a trip to Japan, where I encountered the cultural necessity of honouring materials, I began allowing the natural material to exist in conjunction with the applied colour, so as not to deny its material presence as support.

JMcK: Do you still use more traditional drawing methods?

HM: I maintain a visual diary, which involves notation of process and decision-making as drawing. I draw what I am working on as a way of understanding and observing the work. After the structure is complete, I begin to work on the surface, so then drawing to work out particular painted systems, often referencing growth systems in nature or applied numerical systems. These systems become quite complex, involving multiple layers or sequences. Fence 1979 was almost a transcription of a Kenneth Martin drawing; analysing his systems triggered my own interest in systems.

[image2]

JMcK: You absorbed a minimal aesthetic in New York, which has continued to inform your lifetime’s work. Spatial drawing is an appropriate term for much “sculpture” that was being made in New York in the 70s. How do you describe your practice?

HM: The minimal aesthetic of the time introduced me to a vocabulary, I guess an emancipated language, liberated from interpretation and external reference, a neutral international language. My practice has been described as a dedication to the grid and square. My early works produced in London and New York were spatial, formal drawings in steel on the floor or the wall, sometimes linking those zones together.

Since the mid-80s, the navigation of the gridded square has dominated my practice; it is a relationship I don’t want to leave. My work can appear initially to be renditions or interpretations of the modernist grid, but, for me, the grid is the vehicle or the beginning, a meditative site on which to overlay (the experiential), becoming a site of a personal narrative. My process is slow, meditative and repetitive. The works slowly evolve structurally and in the modulation of the surface. I have worked within this area of investigation for more than 30 years, yet the “grid”, this format, never fails to engage me with its potential and potency. Constraint is a freedom, restraint is focus. I recently read this quote: “A reduced research is a labyrinth of research.” I consider the square grid as a non-hierarchical place, a democratic site, a place of serenity, proportion, surface, tone, balance and harmony.

[image5]

JMcK: What does colour signify in an early work such as The Waiting: Sequel (1985)?

HM: I recognised early in my practice the emotive power of colour, the attendant problems of colour and form, the science, optics of colour being a loaded presence, with multiple cultural associations. I have used numerous blues consistently in my practice, the colour is applied in numerous transparent layers of different blues, so the colour accumulates until I am happy with its presence, density and pitch, similar to tuning an instrument. The Waiting was made after giving birth. I used the spiral in reference to a sense of continuation time bending back on itself, and blue, because it is – or I find it – a restful, reflective colour for that period of gestation in a woman’s life.

JMcK: Can you describe the impact of the feminist movement on your work?

HM: Since the 70s, my work has been in the post-minimal stance, I guess the feminisation of minimalism; the imperfect, the handmade, the gesture of the maker, incorporating the presence of the artist and the autobiographical. The movement created a space, liberated the space to articulate the personal and political. My interest in a formal articulated vocabulary became overlaid with a personal, autobiographical narrative. However, this is a starting point, an entrance to the work, but it is not necessary for the viewer to be aware of this, as I believe a work has to exist autonomously, as an object, beyond me without explanation.

[image10]

JMcK: How did you respond to Australia culturally and personally after living in New York and travelling in Europe?

HM: I have always lived in cities as an adult: London, New York and now Sydney. I moved to Australia in the early 80s and the contrast between Sydney and New York was – is – enormous. I came to Australia with my husband, Bill Wright, the director of the Fourth Sydney Biennale, 1982. We had spent the previous months travelling around the world visiting curators and artists’ studios in research and preparation, so I arrived with a wonderful overview of what was happening, artists’ concerns of that time, new painting, the transavantgarde movement, and we found an equivalent vibrancy in Australia and a strong community of female artists.

We arrived in the extreme heat and vastness that is January in Australia and I found myself in a unique country, this huge island on the other side of the world (sorry, a very northern-hemisphere perspective). The works I made during that time are diaristic. They are notes of exploration and discovery of the strangeness of being in Australia and my situation, as I was pregnant for the first time. The plant and bird life I found quite extraordinary, so exotic and erotic, the fecundity of the vegetation, the flora. These images fed into my feelings about sexuality/fertility; being a stranger, an alien in a new land, about to give birth, leading into thoughts of otherness; being the outsider, the observer. Previously, in New York, I had been working on iconic small dark steel works titled the Weapon series. The underlying emotion of these works had a violent quality, relating to the hand tools and domestic implements that litter female lives. I continued with this small iconic format in Australia, but in wood, brightly coloured, a very different content and imagery, organic, biomorphic, plant like, strange masks. The works were referencing fecundity, female sexuality and a sense of otherness in a new, yet ancient land.

[image6]

JMcK: You have made a Tempus work approximately once a year since 2006. What do these works signify?

HM: The Tempus works began in 2006, the title referring to the passing of time, the act of marking time, by the accumulation or accretion of marks, making almost one a year becoming diaristic or calendar-like. Each work begins with the same proposition of the confluence of two visual archetypes the grid/square and the spiral/circle, using a vocabulary of dots, circles and drilled holes, yet the outcome is always different in this repeated act. The Tempus works are not paintings as there is a physical intervention of puncturing the surface with holes of varying sizes, emphasising the work as an object, hence the optics are illusionary and real. The punctures either follow the grid or the circle and the painted response is either the circle or grid respectively, as in my duality works, the real and the illusionary intersect. I am also using this duality, in this case twining and opposing, within the one work. In our desire to decipher, we cannot perceive both circle and grid at the same time, creating a visual battle, an optical conundrum in our search for order, the eye/mind constantly shift between perceiving the grid or the circle.

I have produced a body of work referred to as The Duality works, Rotation 3 Effigy 2001, being one of this series. In these works I create a structure and then paint a painting of the structure as almost a mirror or reflection of the structure, in an investigation of the slippage or mistranslation between 3D and 2D, a simulacrum, one leaning and the other hanging side by side.

[image7]

JMcK: Can you describe your works and the manner in which you address grief in your work since Bill’s death in October 2014?

HM: As my work has an autobiographical undertow, the initial motivation is an emotional state so it was inevitable my husband’s death would inform the content. The work Reflection/Reach 2015 was made as a self-portrait and it was the first work I made after Bill’s death. I was reflecting on the different circumstance of my life, the enormous loss of my life partner and the state of reaching was my emotional state. There are two presences within the work that overlap and intertwine. They described my life with Bill: we were so much a part of each other that my self-portrait had to include him. The dimensions of the work refer to a bed or a doorway, both places of transition, passage, becoming and, sadly, exiting. The numerical sequence I used was 17 – the birth date we shared. The wood is still evidently raw (unprimed) and then either stained or left exposed. I had not worked with the material, wood, being visibly present for many years, but after my trip to Japan, taken after Bill’s death, I was introduced to the cultural ethos of respect and honesty for the material we use and it became an appropriate approach for the new work that honoured my husband.

I went on to make a partner work a year later, Reflection/Feather 2016. I had started working with whites – the Asian colour of grief – using a reduced, almost bleached-out palette of the primary colours. The colour is functioning like a shadow of what is left, a reflection. Reflection is what is left in life, reflection is what is remembered. The colour in these works bleed into the shadow. The surfaces are stained to different opacities, ghostly layers. Both works respect the material and do not attempt to deny its presence and support.

JMcK: Have the dreadful and unprecedented bushfires in Australia this summer impacted on your studio work?

HM: It is incredible that so soon after the experience of living through the dreadful bush fires of 2019-20 that brought with them extreme environmental destruction, huge travel disruption, the destruction of people’s lives that we are now experiencing the Covid-19 pandemic. We have been social distancing, and our lives have been reduced by being in quarantine at home. Luckily, my studio is within my home but, like many, I am feeling a sense of distraction and futility. In the studio, I am, in a sense, making the most of my social isolation and waiting to see whatever is on the other side of this truly dreadful global event.

Reference

1. Hilarie Mais in an email to Janet McKenzie, 9 July 2009.