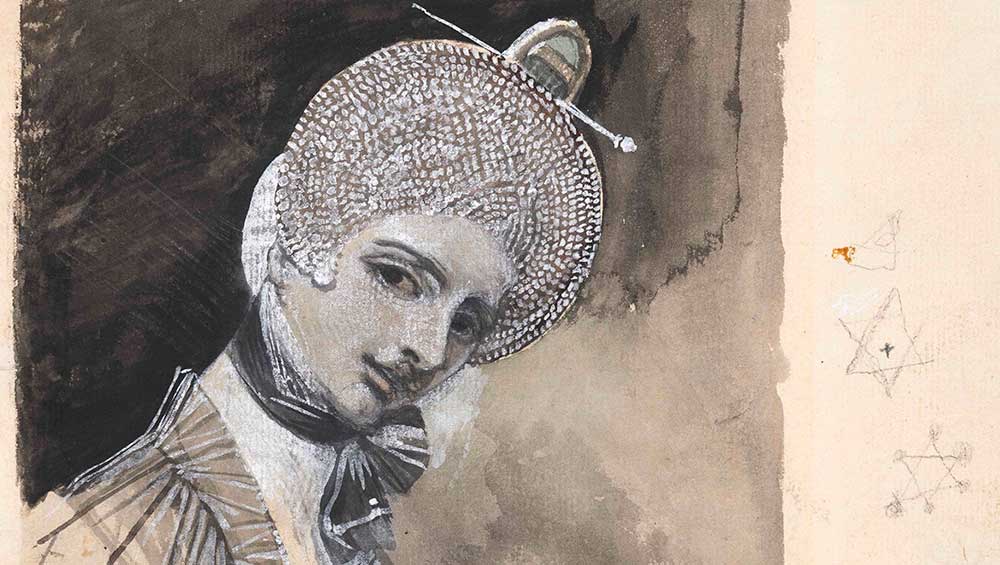

Henry Fuseli. Sophia Fuseli in an elaborate braided head-dress, c1795 (detail). Pen and black ink, brush and watercolour and opaque watercolour, 17.4 x 14.4 cm. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1965.

Courtauld Gallery, London

14 October 2022 – 8 January 2023

by JOE LLOYD

The Nightmare (1781) is one of those paintings that precedes the fame of its painter. It depicts a woman asleep, sheathed only in a diaphanous white sheet. Her prone pose resembles death. A squat incubus perches on her chest and gazes out towards the viewer, while a demonic horse’s head cackles in the background.

When The Nightmare was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in London, audiences reacted with shock at its eroticism. It soon became very popular. Multiple versions were created. Another artist translated it into a bestselling engraving, and Georgian London’s satirical cartoonists adapted it to parody politicians. It fed into the in-vogue gothic literary movement, most famously inspiring a scene in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). It remains one of the most recognisable paintings of the 18th century.

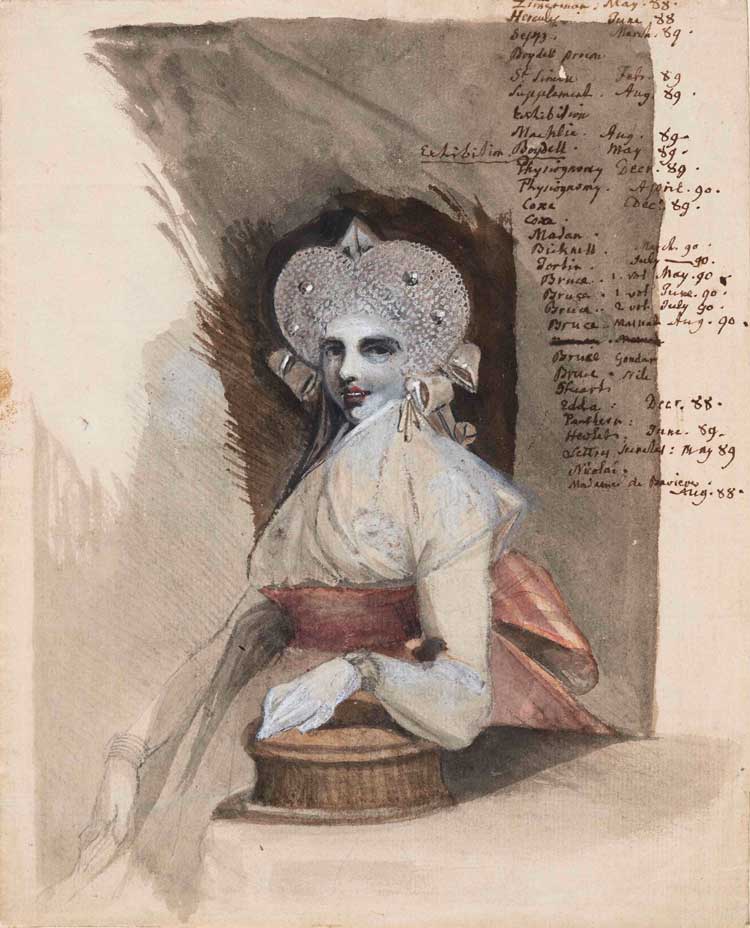

Henry Fuseli. Sophia Fuseli, seated at a table (drawn over a list of Fuseli’s articles for the Analytical Review), c1790-91. Pen and brown ink, brush and watercolour, over graphite, heightened with white opaque watercolour, 22.7 x 15.7 cm. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1965.

Its painter, Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), has fared less well. He was born Johann Henrich Füssli in Zürich and trained as a Protestant preacher, but left in 1761 after being persecuted by the family of a corrupt magistrate he had helped to expose, going first to Berlin and then to London in 1764. After a spell as a writer, he decided to devote himself to art. Working as the Enlightenment gave way to the dark shadows of Romanticism, his literary and supernatural subject matter gradually became respectable. Celebrated by fellow artists, he became a pillar of the English art establishment, serving as the Royal Academy’s Professor of Painting and Keeper. The Academy was then based in Somerset House, where Fuseli lived for the last two decades of his life and where the Courtauld is now.

Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism brings Fuseli back to his old home. It collects about 50 of his drawings from various international collections and comes accompanied by new research into his life and work. It reveals a figure who is equal parts fascinating and troubling, whose art veers between provocative licentiousness and a reactionary terror. Behind Fuseli’s veneer of sophistication lurked a fear of revolution and social breakdown, compounded by the toppling of regimes in the United States and France.

Henry Fuseli. Woman in a Sculpture Gallery, 1798. Graphite, pen and black ink, brush and watercolour, heightened with white opaque watercolour, 41 x 24.7 cm. Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kupferstichkabinett.

This does not make Fuseli sound like a very pleasant man, and the Courtauld’s curators make clear that he wasn’t. He was famously conceited, once declaring himself the only person in England who knew how to paint properly. More alarmingly, he was exceptionally misogynistic, picking up the worst traits of both Zurich’s puritanical moralism and London’s libertinism. The present exhibition focuses on three series of works – his “fetishistic” pictures of complicated neo-classical female hairstyles, his depictions of women viewed from behind and his images of courtesans – that each present a man simultaneously compelled and repulsed by femininity.

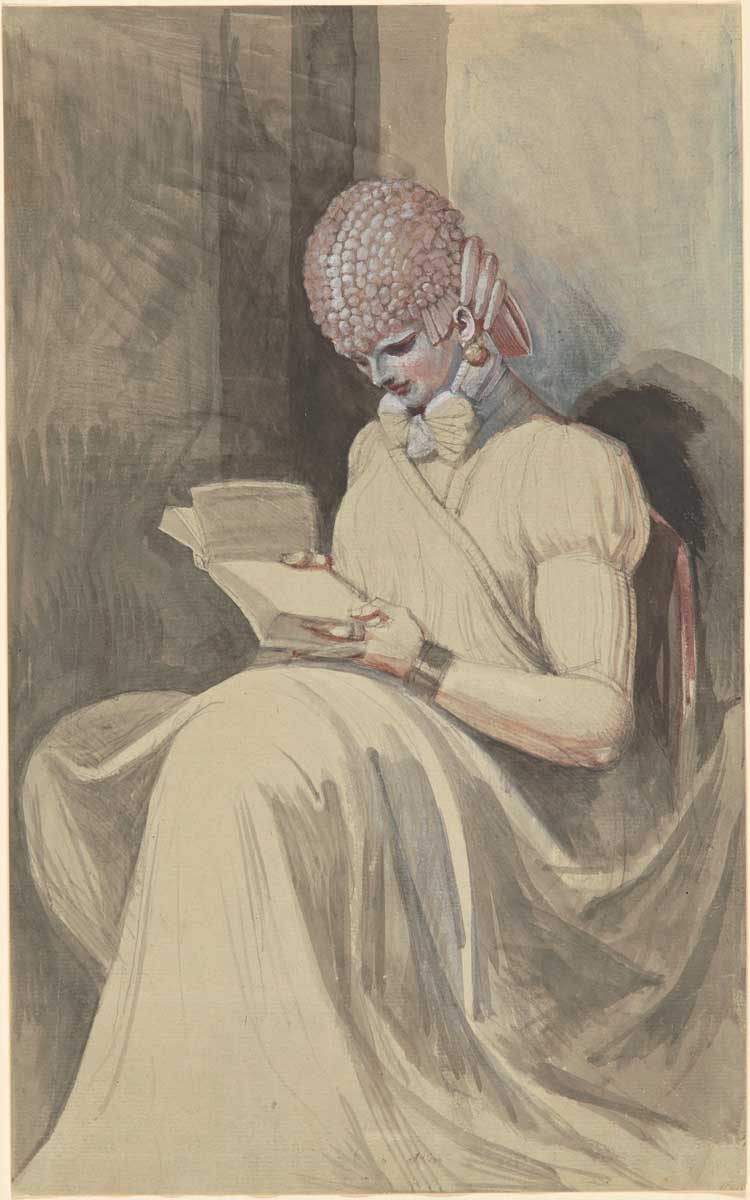

Henry Fuseli. Seated Woman (Sophia Fuseli?) in curls, reading, c1796. Brush and watercolour and opaque watercolour, over graphite, traces of red chalk, 36.5 x 22.8 cm. Zürich, Kunsthaus Zürich, Collection of Prints and Drawings, 1938.

The first of these thematic sets, and perhaps the mildest, stars his wife, Sophia Rawlins, who was more than 20 years younger than Fuseli. Before they married, she had been a professional model. Sophia appears in a bewildering array of poses. Sometimes Fuseli captures her as an earnest, wide-eyed youth, sometimes as an almost demonic presence with a pallid face and wicked grin. Sophia ran through an extraordinary run of hairdos, many of them inspired by the ancient Roman busts at the Capitoline Museums. Fuseli draws them with extreme detail, deftly translating their complex, geometric patterns. In one drawing, from 1796, which shows her reading, she has a tightly knotted dome of tiny spheres that seems to defy nature. In another (c1790-92), she appears to be caught off-guard checking herself in a mirror, her hair fanning out like a wafer.

In another, from 1798, her hair is trapped into long finger-like strips. This image is fraught with contradictions. She stands in front of a fireplace, a symbol of propriety, wearing an open cloth exposing everything from the waist down. Two fairies, perhaps household gods, busy themselves around her. Fuseli has profaned an image of domestic uprightness with naked eroticism. If this image had circulated in public, Fuseli might not have enjoyed the success he did, and Sophia’s reputation would have been damaged irrevocably. Small wonder that she is reported to have burned many of her husband’s “shockingly indelicate” drawings after his death.

Henry Fuseli. Woman with long plaits teasing a figure trapped in a well; and subsidiary study of Ezzelin and Meduna, 1817- 22. Graphite and black chalk, brush and watercolour, 32.1 x 19.4 cm. Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kupferstichkabinett.

Extravagant hair, of course, calls to mind the mythological figure of Medusa, whose head was topped by a writhing mass of snakes. Fuseli makes this connection explicit in one 1799 drawing, in which Sophia sits next to the Medusa Rondanini, an antique bust of the gorgon. Fuseli spent eight years in Rome between 1770 and 1778, and echoes of classical sculpture and mythology are everywhere. A c1790-91 picture of Sophia shows her with huge painted lips, visible nipples and bared teeth – then signs of sexual immorality – holding the lid of a basket, like a new Pandora about to unleash her box of horrors on the world. Another, from 1795, has her sewing on to a cloth the name of Nemesis, the ancient Greek goddess who punishes the hubristic. Is Fuseli in line to face her wrath?

Henry Fuseli. Two courtesans in a theatre box, with fantastic hairstyles, c1790-92. Pen and brown ink, brush and watercolour and opaque watercolour, over graphite, 17.9 x 16.2 cm. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1965.

Fuseli’s interest in depicting women from behind also has a classical lineage, going back to Praxiteles’ lost Aphrodite of Knidos. But this does not make them any less prurient. By anonymising his subjects, he could turn them into objects of male desire. One tiny drawing (c1796-1800) shows the back of a woman whose hands are laid on a table raised by two unmistakable phalluses. More often, the women are clothed, but as in The Nightmare barely: the curves of the body can be seen all-too clearly. There might be some satire here, mocking the way fashion (and fashionable hairstyles) distort the body, something that would become a hot topic in Regency England.

Henry Fuseli. Fool on the end of a prostitute’s rope, c1757-59. Pen and grey-brown ink, brush and watercolour 11.8 x 10.6 cm. Zürich, Kunsthaus Zürich, Collection of Prints and Drawings, Donated by C. Meyer, 1826.

But Fuseli’s fear of the feminine is also clear even from behind. One back view from 1795 renders its subject chunkily monolithic, with one arm appearing to end in a pinion, another shrouded in darkness. It looks as if she is concocting some shadowy business, a crime from which the artist wishes to spare us. Fuseli drew various scenes depicting women handling powerless men or children. An ink and watercolour work drawn c1757-59, when Fuseli was just a teenager, has a prostitute hook a jester with a rope. An 1817 drawing sees a courtesan doing something with a needle to an indistinct body on a slab, while one from c1790 has two witch-like courtesans prodding and cutting an obscured object. It is almost as if, like many present-day conservatives, Fuseli himself cannot comprehend what it is he fears.