Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London

22 January-13 April 2003

According to classical legend, Ariadne, daughter of Pasiphae and the Cretan king Minos, fell in love with Theseus, the Athenian hero. By giving him a length of silk thread she helped him to escape the labyrinth in which the man-eating Minotaur lived. Theseus promised to marry Ariadne during their journey to Athens but instead he betrayed her, abandoning her on the deserted island of Naxos. She was later rescued by the god Dionysus.

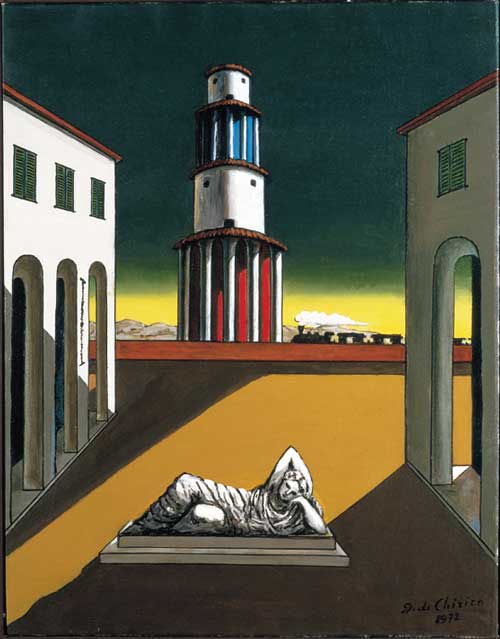

The melancholic story appealed to classical artists who typically portrayed her slumbering upon empty shores. For Greek born, Italian de Chirico, the abandoned princess took on a rich metaphorical meaning. She represented the classical past of his homeland and was also singled out by Friedrich Nietzsche, with whom de Chirico had an artistic affinity, as being a symbolic figure with contemporary relevance. For Nietzsche the labyrinth from the Greek myth could be equated, in contemporary terms with the complexity of life's enigmas. The thread, according to Nietzsche, was a necessity in life, enabling a path through the confusion of certain crises in life. Ariadne is portrayed as a statue in de Chirico's paintings, based on the famous marble masterpiece in the Vatican.

Painted first during de Chirico's early years in Paris, when he was intensely lonely, Ariadne became a symbol of exile and loss. The works resonate with the loneliness of the dispossessed; they were influential on Salvador Dali, Max Ernst and René Magritte. In the wider context of Surrealism they were very important works.

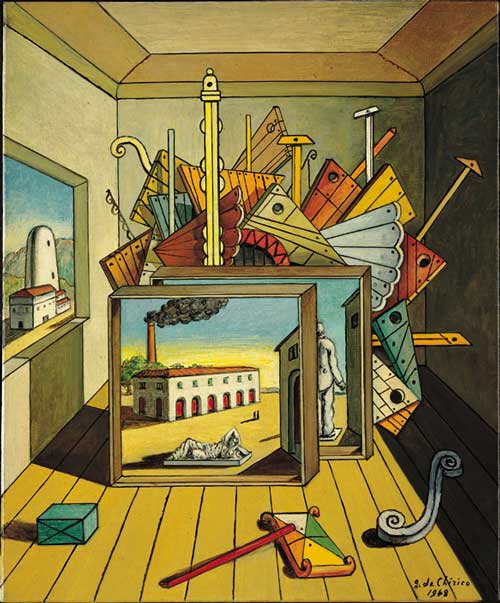

Giorgio de Chirico and the Myth of Ariadne, brings together key works (18 paintings) from the Ariadne series from private and public collections around the world, as well as related drawings and sculptures. This is the only European venue for this important exhibition organised by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The exhibition confronts the contentious issue in de Chirico's career, where, having painted the myth of Ariadne in 1912-13 he then returned to it later in his life and produced what were virtually copies of the earlier works. Referring to the intense creative insight experienced on an early trip to Versailles, de Chirico wrote:

I saw that every angle of the palace, every column, every window had a soul that was an enigma. I looked about me at the stone heroes, motionless under the bright sky, under the cold rays of the winter sun shining without love like a profound song…I experienced all the mystery that drives men to create certain things.

The curator of this exhibition, Michael Taylor, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at Philadelphia Museum of Art states:

When one re-examines the Ariadne theme through the entirety of de Chirico's career there emerges a continuity between these early paintings, initiated at a time of intense loneliness during his first years in Paris before World War I, and the later works created when he abandoned modern art in favour of the Old Masters, thus alienating him from the very painters he influenced. By the time he returned to the Ariadne theme in the 1930s he equated her with painting itself, her golden thread becoming a metaphor for the artist's quest for knowledge and perfection in painting.

Press reactions to the show in London belong to the ongoing debate as to the value and authenticity of response of de Chirico's late Piazza d'Italia paintings, whether or not they were a form of self-plagiarism. In The Man Who Faked Himself, Rachel Campbell- Johnston (The Times, 22 January 2003) wrote:

The spectator is confronted by a roomful of all but identical Piazza d'Italia paintings that look suspiciously like some cultural version of a spot-the-difference game. Had he simply run out of ideas? That was the question asked of him during the last three decades of his life. De Chirico himself argued that he was not copying but making 'extremely exact variations'.

Laura Cumming (Observer Review, 26 January 2003) wrote:

This is either the longest enigma variation in the history of art or the worst case of compulsive repetition..

Of the late work she continues,

A forger or a pop artist, 40 years in advance?

The arcade isn't so dark; in fact, the whole picture is visibly brighter and now comes in selected colours. Pink Ariadne, gold Ariadne, and turquoise Ariadne. You can see why Warhol thought he spied a precursor and even silk-screened his own four-panel version. But de Chirico was no sort of pop artist, despite enjoying the homage. Nor is he quite the postmodernist the curators want to make of him.

Martin Gayford (The Sunday Telegraph, 26 January 2003) concludes that where the early work was poetically inspired the work produced between 1950 and his death in 1978 (some dated decades earlier than they were painted), "look like student copies, and give the impression that the poetic obsessive of 1912 had metamorphosed into a cantankerous, talentless old nutter". Charles Darwent (Independent on Sunday, 26 January, 2003) is a little kinder than Gayford,

Before post-modern appropriation made copying your own work kosher, stepping backwards in this way was frowned upon. De Chirico's reconversion to de Chirico is an embarrassment his apologists have kept discreetly locked away. Now, this excellent show has brought it out into the open, and done the artist a huge favour in the process.