Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York

5 November 2021 – 13 June 2022

by NATASHA KURCHANOVA

The first US retrospective of this Turner-Prize-winning British artist is a tour de force: every detail of the exhibition is thought through, resulting in a comprehensive overview of the artist and her more than 30-year career. The title itself, in its repetition of the artist’s last name as a gerund of the verb “wear” introduces the theme of the show as that of repetition with a semantic twist, a change of meaning that is not observable with the naked eye, but is based on context, on our knowledge of the artist and her subjects. The stories that Wearing’s images evoke are either implicit – hidden behind masks that have become a kind of a second skin, defensive shields that protect the vulnerable egos of their wearers; or explicit – written on sheets of paper, engraved on pedestals or unfolded through action on the screen. The viewer is invited to view or listen to these stories and empathise with their protagonists.

[image5]

The exhibition is arranged over four galleries in the building adjacent to Frank Lloyd Wright’s rotunda. It begins with sculptural, photographic and video work that reflects Wearing’s interest in observing her community and the people she encounters by chance on the streets of London. The second gallery displays photographs, videos and sculptures that feature intimate partnerships and families, including Wearing’s own; the third features her photographic portraits of herself in the guise of artists who influenced Wearing’s thinking; and the fourth houses an installation that traces one of Wearing’s principal subjects, her evolving relationship with her own image from the beginning of her career until now.

[image16]

While varying in media and the time of their making, in all the works in the first gallery Wearing presents a situation in which the viewer witnesses a social event of sorts in which individuals or groups distinguish themselves by undertaking a challenging or even heroic deed or making a public statement, however simple. I say “presents” rather than “represents” because it appears that the artist tries to erase the time lapse that marks the difference in meaning between the two concepts by turning our attention to identification as a creative act. Each work captures a moment in time that makes it possible for us to see a person as a character who has a story to tell, or something to say. Sometimes, it is written on the label. For instance, as we enter the first gallery, we are greeted by a small-scale model of Wearing’s sculpture of the prominent British suffragette Millicent Fawcett (1847-1929). The full-scale sculpture was erected in 2018 in Parliament Square in London to commemorate the centenary of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which gave the right to vote to some women in the United Kingdom. Fawcett stands upright facing the viewer and holding a banner that reads: “Courage Calls to Courage Everywhere.” The evocative power of this statement speaks to us directly, compelling us to empathise with the character of this extraordinary woman in the moment we are facing her.

[image8]

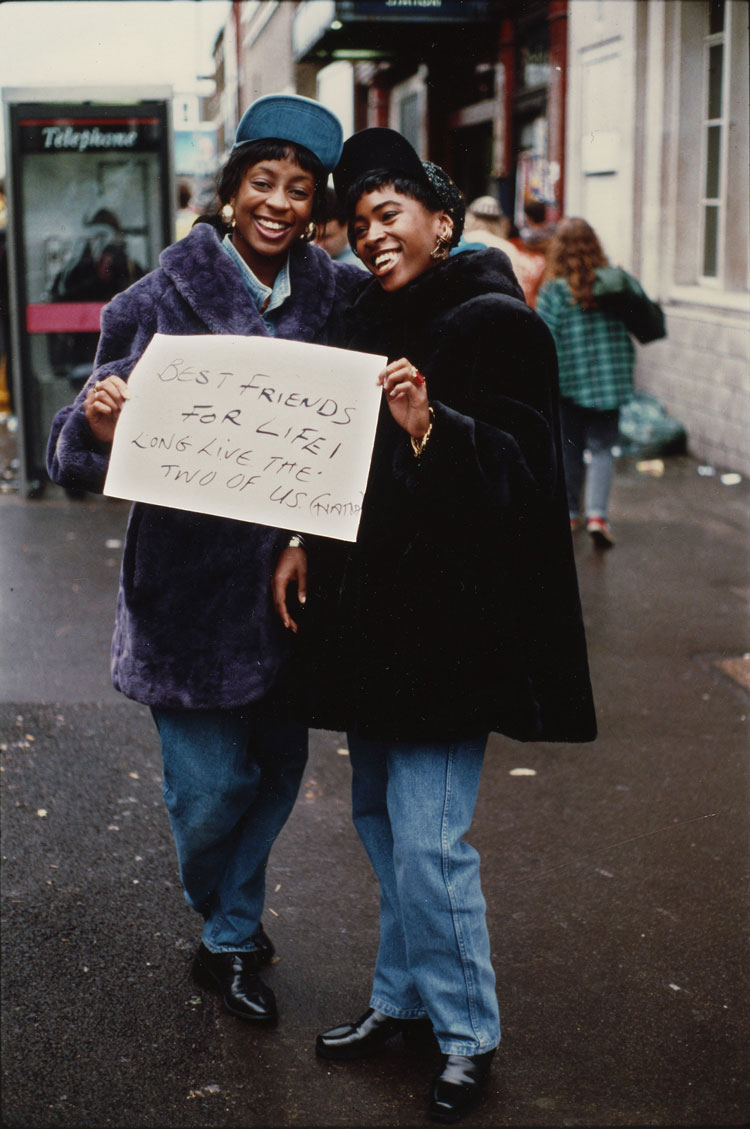

Immediately across the room from this model, we see an earlier series of photographs entitled Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say (1992-93), in which people hold handwritten signs that display incidental thoughts that were on their minds at the time the pictures were taken. As in many of her projects, Wearing chose her subjects randomly, asking strangers on London streets to each write on a sheet of paper what they were thinking about at that moment. She then photographed them holding these signs as identifiers of sorts. The evocative immediacy of these photographs recalls the tradition of social photography practised by August Sander (1876-1964) and the instant news production technology of today’s social media. Even though the people in these photographs are strangers and we know nothing about their lives, as viewers, we form our opinions about their characters according to the words they chose to write. A smiling woman holding a sign that reads “I really love Regents Park” evokes quite a different sentiment in us from that of a young man in a business suit who wrote on his sheet of paper: “I am desperate.” Our personal responses to these images would vary as well depending on our own characters and view of the world, but it is difficult to remain indifferent to this display of humanity in all its faults and glory.

[image13]

The emotional intensity of Wearing’s work reaches its peak in her videos. Every one of them has the power to draw us in by the emotional pull of the action, expressed in a personal story, usually of a traumatic nature. In the 2010 documentary Bully, for instance, we are witnessing the restaging of a bullying event that traumatised the documentary’s protagonist, a young man named James. He has a short, punky haircut and an anxious demeanour. In the course of a nearly eight-minute video, a group of nine actors trained in the method-acting technique are directed to re-enact a traumatising scene that James experienced when he was a child. The emotional intensity builds up as the characters verbally assault James and then regroup to enable him to confront them head-on, literally – by pressing his forehead against theirs and exploding in anger: “You – you think you are tough? I will show you tough when I place a fucking bullet in your forehead …” It is nearly impossible to convey in words the burning rage captured on the video. Perhaps the impossibility of conveying this rage other than by acting it out speaks for Wearing’s interest in showing unhinged emotion – unmasking the rage that has crippled James for years. This performance serves as therapy for him, allowing him to express his pent-up emotion in a cathartic and healing way.

[image6]

Another video in which Wearing shows unbridled emotive action is Dancing in Peckham (1994), in which she dances with abandon in the middle of a shopping centre, appearing completely unselfconscious and oblivious to her surroundings. Interestingly, as improvisational as this dance looks, Wearing has rehearsed it in one-minute segments to the songs of popular rock bands, such as Queen and Nirvana.1 Just as in Bully, this performance looks spontaneous, but in fact requires training or careful preparation. Dancing in Peckham may be viewed as one of the many self-portraits Wearing has made in her career and one of a relatively few that does not feature her in a mask, impersonating either herself, a family member, or a revered artist with whom she identifies. Even without a mask, she still is barely showing us her face, turning sideways or down and generally looking away from the camera. She allows us to see only her dancing figure and the environs of the shopping centre, but never a closeup of her face or her gaze.

[image14]

The video Fear and Loathing (2014) is shown in a close proximity to Bully. It is just as emotionally charged, but the emotion is repressed and subdued. In this work, we see several people who have been traumatised by horrific events looking straight at the camera. Unlike James in Bully, they wear masks that cover their faces perfectly, leaving openings only for the eyes. Unlike James, they tell their nightmarish stories dispassionately, in monotonous voices, as if the masks shield them from any display of human emotion, eliminating spontaneity and vivacity. It is as if their personal traumas have congealed their faces on to a mask, protecting them from the world and from being hurt further, but also turning them into automatons of sorts, unable to recover their joy of life and self-confidence.

[image2]

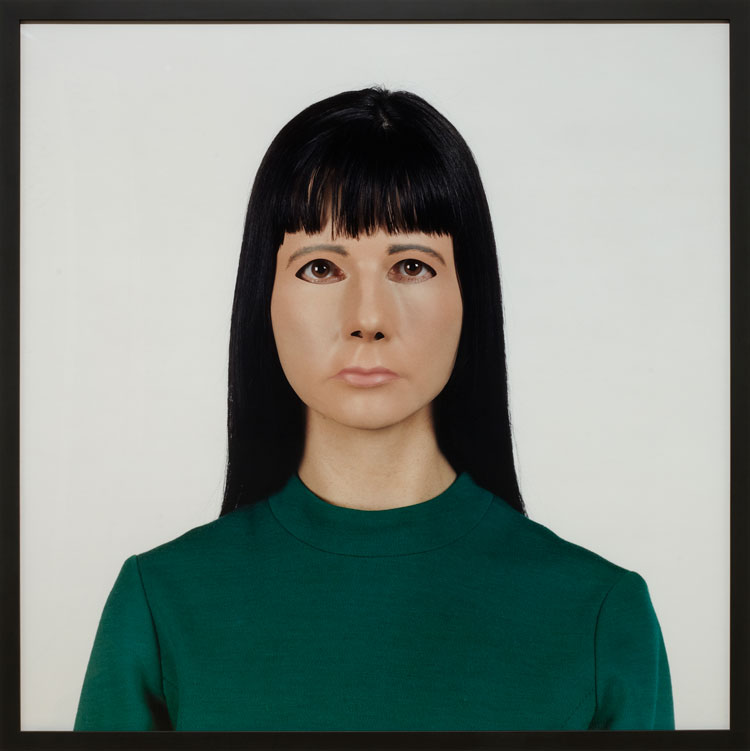

Wearing made her first masked self-portrait in 2000, at the turn of the century. In this work, her likeness is staring at us from a larger than life-sized photograph, her face contoured by a shell of a mask. The portrait faces us head-on, like those seen on Ancient Egyptian funerary images. Unlike those images, however, the artist’s face is not rendered as vibrant and alive, but is enclosed in a sarcophagus of a mask with only the eyes visible, peering out of the shell. When eyes are the only sign of life visible in the picture, the orientation of the gaze and the “look” it creates are paramount in making the subject understood. Each of us reads this “look” differently, depending on our views and personal history. For instance, the direct stare of this self-portrait may be read as Wearing declaring the mask to be her artistic trademark. Alternatively, it can be interpreted as her insistence on hiding herself, except for her direct, unapologetic stare.

[image7]

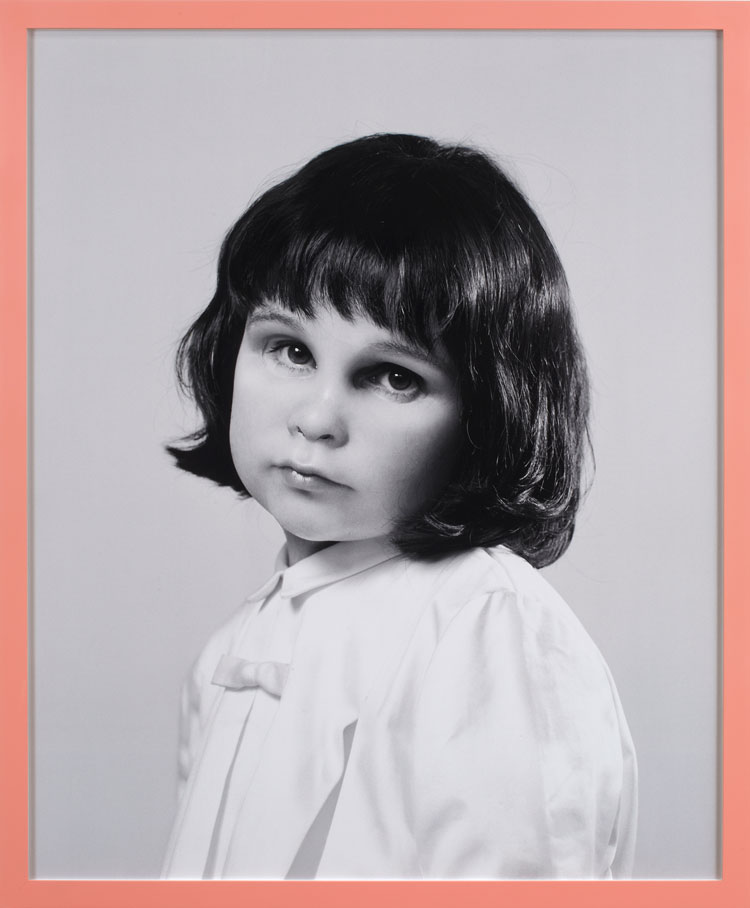

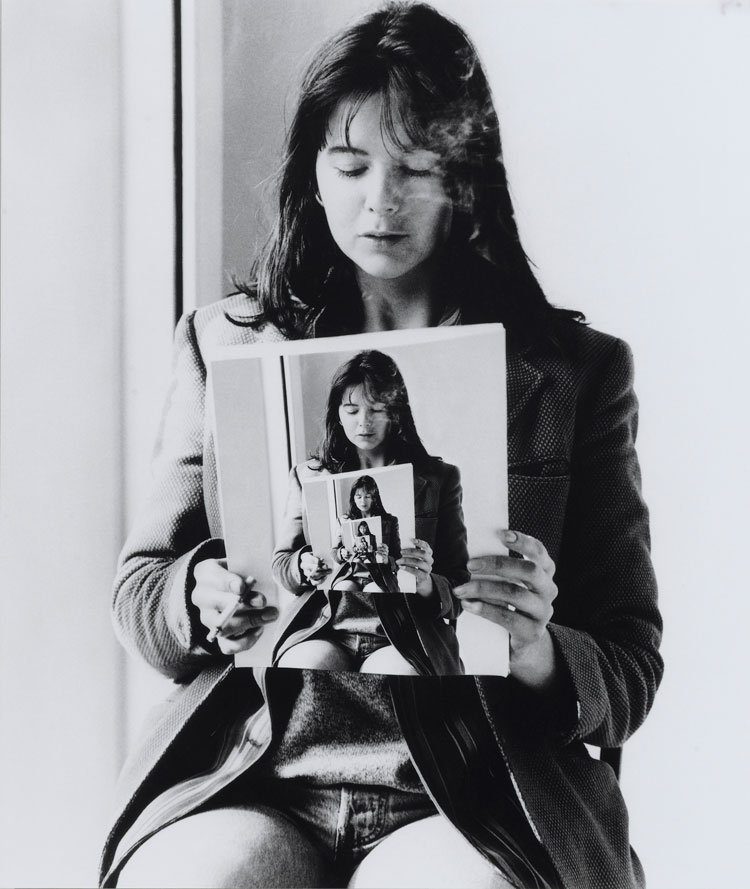

Following this portrait, Wearing made a number of images of herself in a mask. Because her entire face except for the eyes is hidden, facial expressions moulded into masks become hieroglyphs of sorts that allow us to “read” the artist at different ages. The format of her self-portraits at ages three, 17 or 27 is very similar: non-smiling, bust-size, looking at the viewer. However, her “looks” are different: as a three-year-old, her image conveys an air of vulnerability and dependence through a three-quarter turn of her head from down up. As a 17-year-old, Wearing stares us down with her head-on gaze. As a 27-year-old, we see a photo strip photobooth-style, with four nearly identical pictures of the artist.

[image9]

A close scrutiny reveals minuscule differences in a slight turn of the head and the direction of the gaze. The artist as her Ideal Self is shown as a teenage-looking girl in a short skirt and high heels striking a pose while standing on top of a box that serves as a makeshift stage. In Me As an Artist in 1984, she is sitting in front of a surrealist-looking painting and holding a nude female figurine with traces of something red on it – blood, perhaps? Her demeanour and the calm expression of her masked face contradict this disturbing figure. All Wearing’s portraits are staged in such a way that they trigger our imagination by making us wonder what the real story is. What is she hiding? What is behind the mask?

[image10]

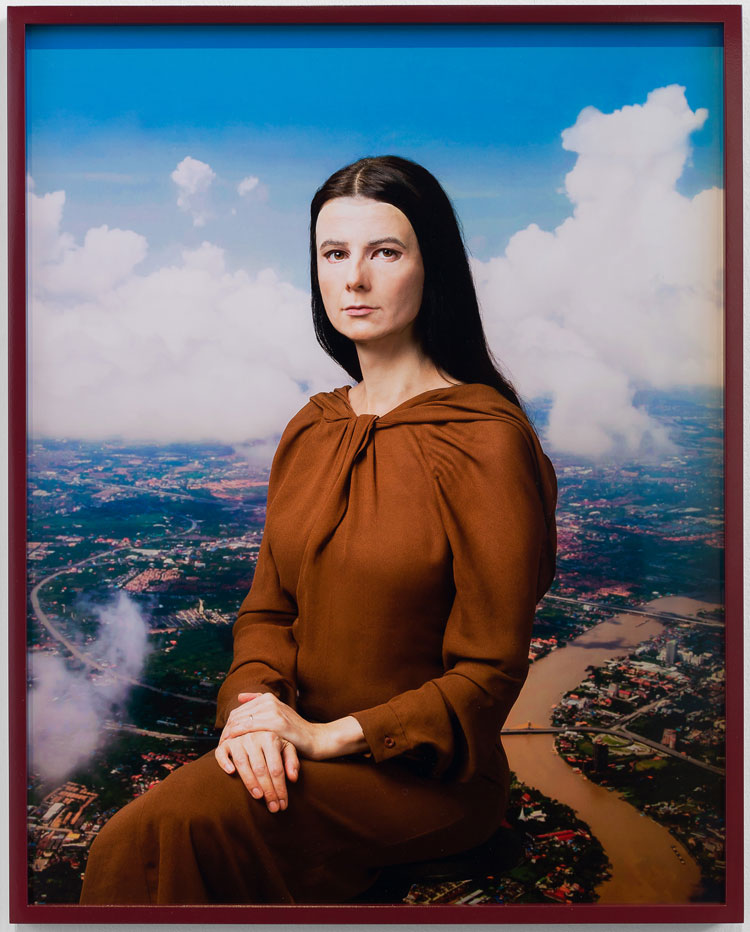

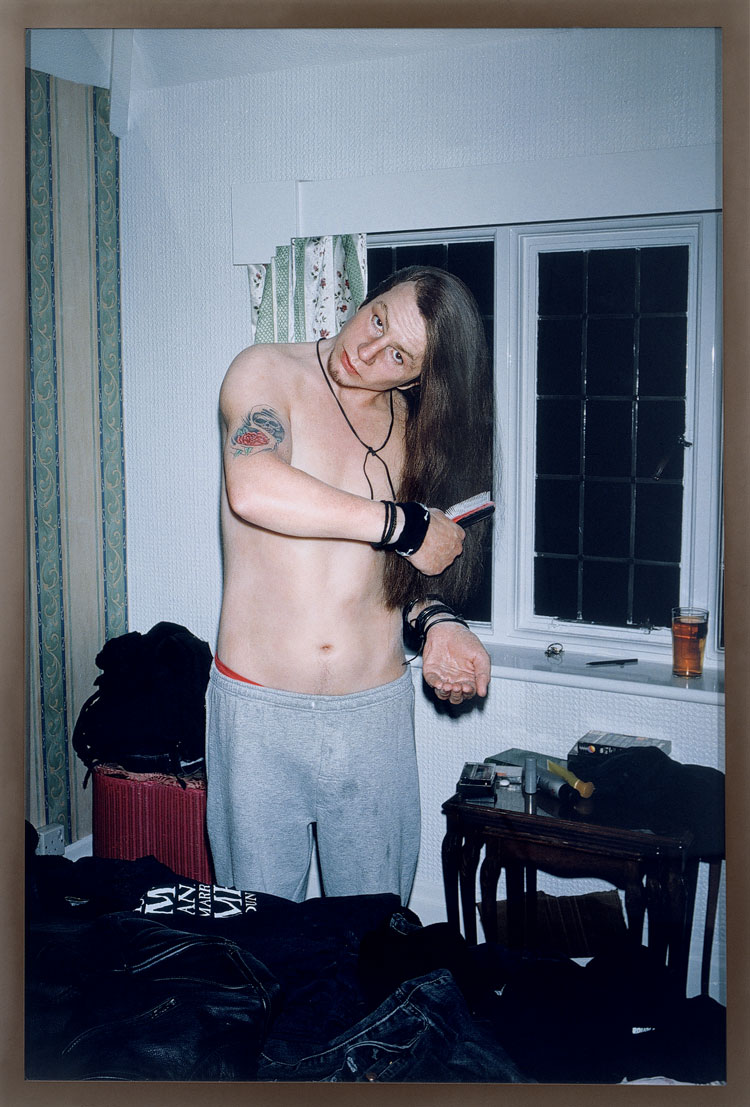

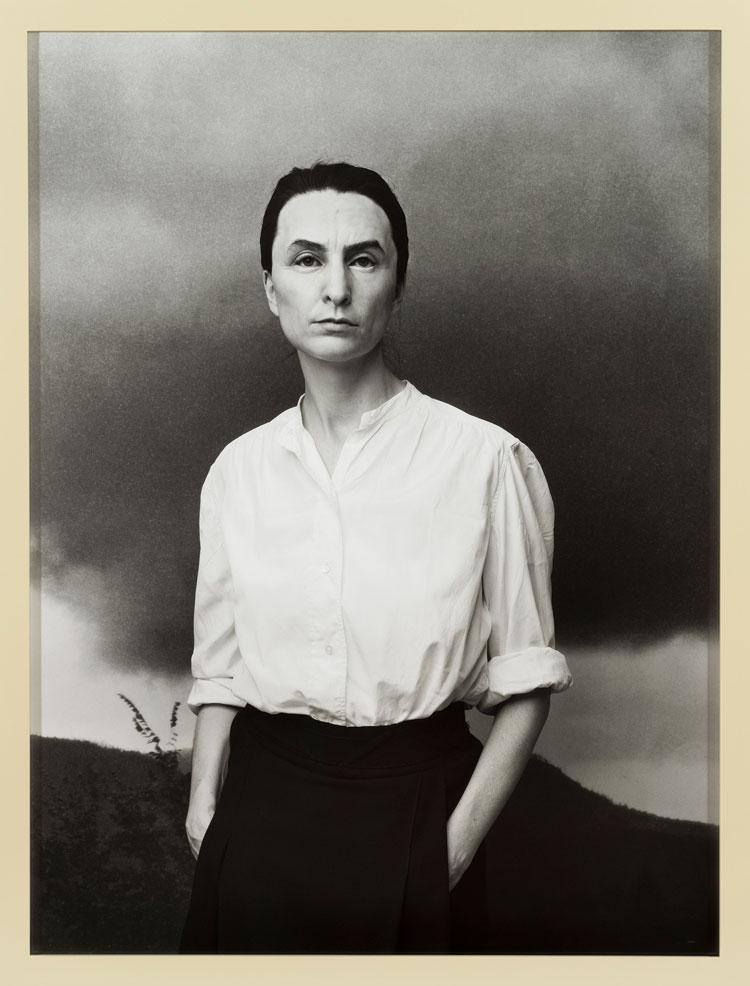

This question is only partly answered in Wearing’s portraits of herself in the guise of artists she admires: Diane Arbus (1923-71), Claude Cahun (1894-1954), Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), Andy Warhol (1928-87) … Just like her self-portraits, her likenesses of these figures are shot predominantly head-on. There are rare exceptions of photographs staged with mirrors, for instance a double-portrait of herself and Cahun, or herself as both Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) and his wife, or herself as Meret Oppenheim (1913-85), who is shown from multiple points of view in a photograph Wearing shot Man Ray-style.2 In these images, Wearing appears to enact her own fantasy of transforming into those famed artists and staging their imagined presence in front of the camera. Here, the artists she identifies with are represented by canonical signs or stories associated with them – Arbus holds a camera; Warhol appears in drag displaying a scar on his ribs; Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-89) holds a cane with a skull; O’Keeffe stands in front of a desert-like landscape.

[image4]

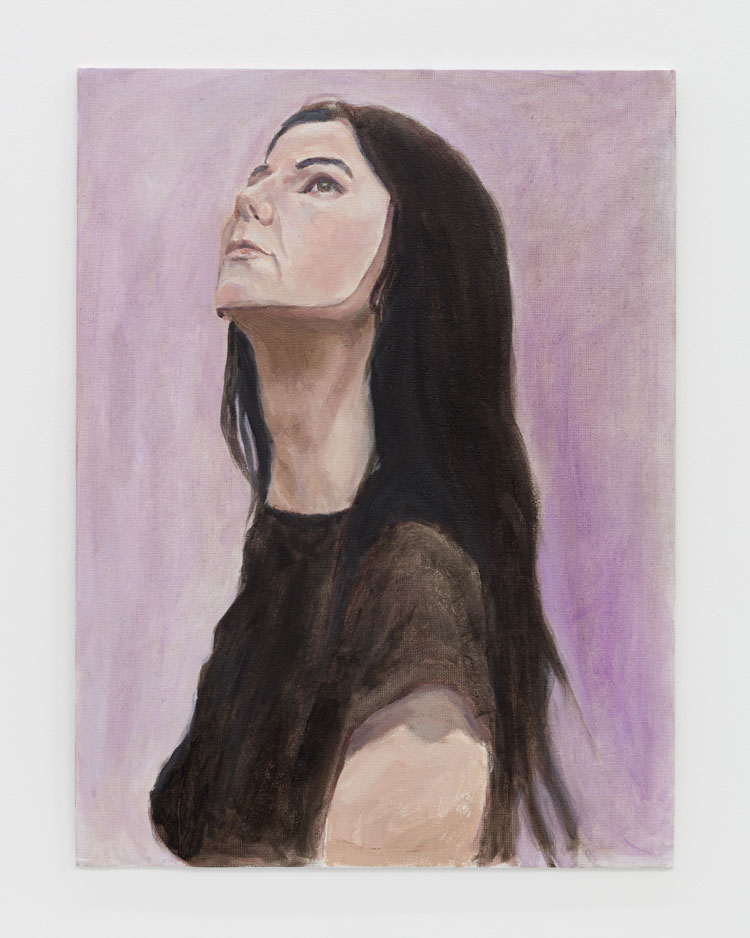

The concluding section of the retrospective is dedicated mainly to Wearing’s most recent work, including self-portraits she painted during the Covid lockdown. These and her self-portrait from 1985 are the only paintings in the show, and they strike the viewer as skilful and beautiful, with Wearing representing herself as melancholic and serene. Just as in her photographic work, the gaze defines the mood of the work: the artist explores all the angles from which she could paint herself: looking straight ahead, up, down, sideways. The expansive Rock ’n’ Roll 70 (2015), in which Wearing portrayed herself in ways she imagined she might look 20 years on, at the age of 70, occupies two adjacent walls of a gallery. The artist printed these photographs wallpaper-style, in a repeating grid of 15 rows, each with 15 different photographs of herself, sometimes smiling and more frequently not, perhaps making us wonder how we might look at this age.

The masked selfhood and outward representation that is the theme of the show makes Wearing, Gillian (2018) perhaps the most revealing work in the exhibition. This is a video installation in which the artist filmed herself and hired more than 15 performers to portray her. In this video, the artist speaks to us directly, describing herself and her work. “Hello, I am Gillian Wearing. I’m an artist. I do not like to be on this side of the camera … Watching me being me alienates me from me, and I do not recognise myself. That’s why I placed an advert online looking for people who’d want to be me in this film … One of my hopes is that the performers will be able to be a more convincing me than me … Portraits and identity are the things that interest me in my work. I believe identity is fluid and it is what you absorb from the world around you and internalise. But what you reveal of yourself to the world, that’s how other people define your identity. It’s really about putting myself on the line, and that comes with the risk of being judged and laying myself bare to people’s judgments, but such is life … We all wear masks. We’re all actors. When you leave your front door in the morning, you’re putting on a performance for the world … Do you think or believe you know what a true self is? What is a true self anyway?”3

References

1. Endnote 1 in Gillian Wearing: Wearing, Gillian by Jennifer Blessing. In: Gillian Wearing: Wearing Masks, published by Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2022, page 82.

2. Ibid, page 64.

3. Wearing, Gillian. Ibid, pages 30-41.