MK Gallery, Milton Keynes

12 October 2019 – 26 January 2020

by JOE LLOYD

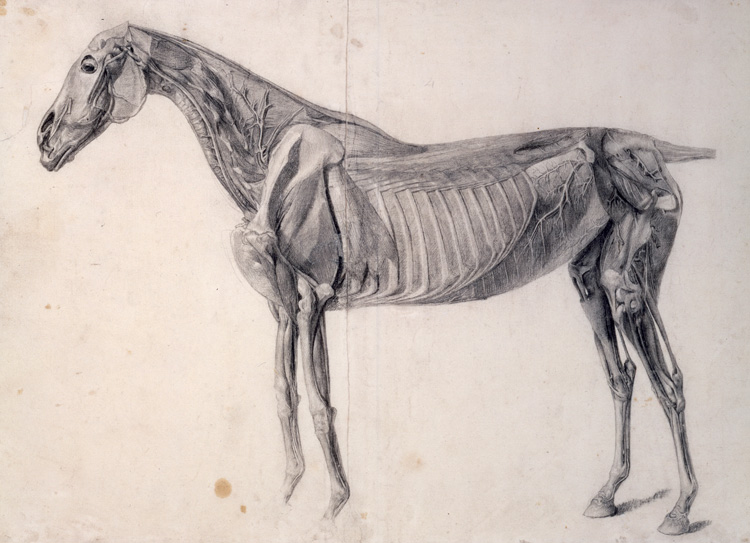

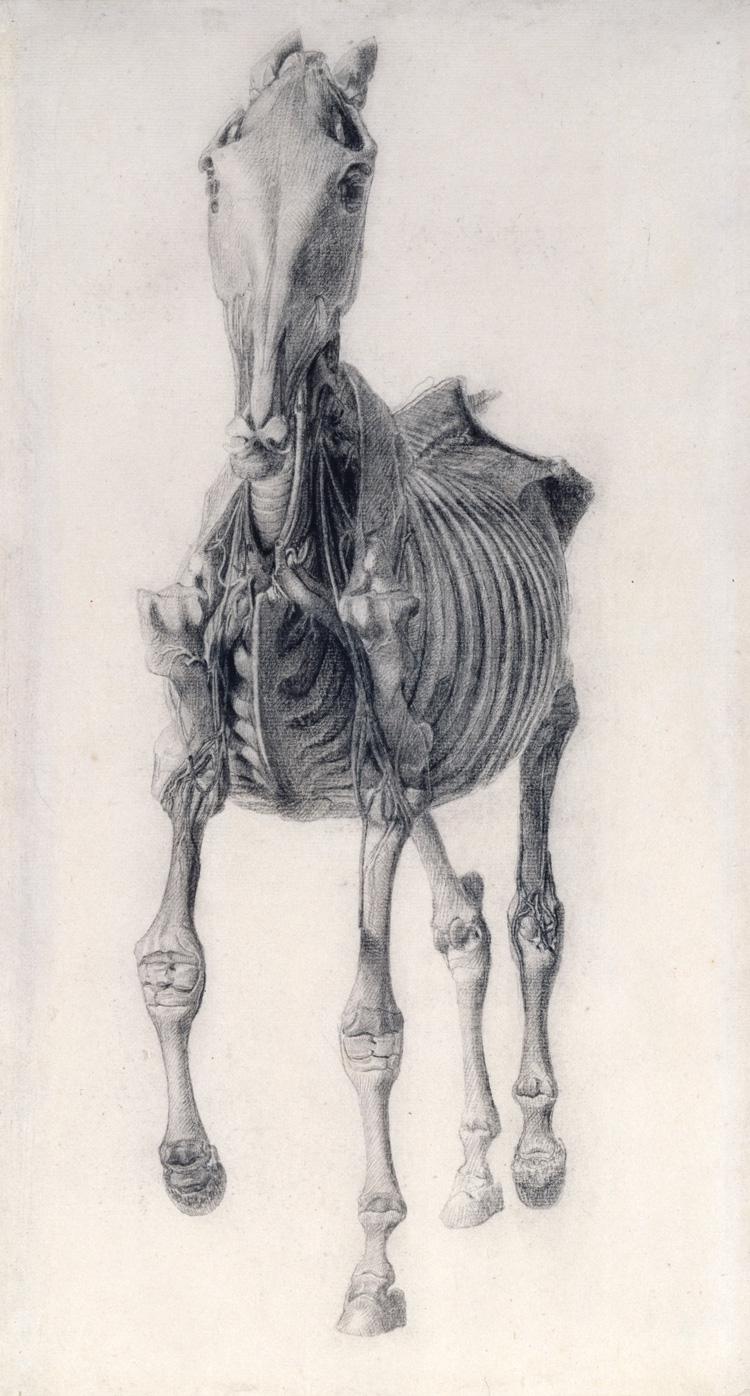

You might not guess it from his depictions of horses before placid parklands and prim Georgian mansions, but the art of George Stubbs (1724-1806) was born in blood and guts. As a young artist in 1756, he retreated to rural Lincolnshire and, for 18 months, set about dissecting equine corpses. He killed a succession of 12 horses, before filling their blood vessels with wax and suspending them by hooks. Thus prepared, he would gradually strip off their skin, at each stage drawing what he beheld. The resultant book of engravings was not published until 1766, but the drawings presaged a raft of commissions and established his reputation as the most anatomically accurate painter of horses.

[image3]

Stubbs is now the subject of All Done from Nature, an expansive survey at MK Gallery, which compiles about 80 works to form the most substantial exhibition of the artist since 1976. It is odd that it has been so long in coming. The past century has seen Stubbs, who soon after his death was regarded as a mere horse-painter, elevated to the highest ranks of British art. “Horse-painter,” wrote the poet and critic Geoffrey Grigson, in a 1940 essay that set the tone for much scholarship to follow, “is not the right description for him at all. He was a painter who painted horses.”

[image8]

In 1957, a major exhibition of Stubbs’s work took place at the Whitechapel Gallery, a year after the landmark pop show This Is Tomorrow and a year before the gallery’s groundbreaking retrospective of Jackson Pollock. His reputation has not diminished since. Contemporary artists as diverse as Hans Haacke, Jeff Wall and Mark Wallinger have referenced his work, and the practices of Damien Hirst and Berlinde de Bruyckere feel indebted to it.

What informs Stubbs’s particular appeal to modernity, while equine-inclined successors such as Edwin Landseer and Alfred Munnings languish? For one, there is his empirical accuracy, which stands at the threshold of modern scientific exactitude. His horses are real flesh-and-blood creatures, transposed from life down to their specific markings and musculature. His late, unfinished masterwork of drawing – The Comparative Anatomical Exposition of the Structure of the Human Body, with that of a Tiger and Common Fowl (1795-1806) – would extend this rigour to people, birds and cats, an enterprise that seems to pre-empt Charles Darwin’s concept of common descent.

[image2]

Stubbs’s precision was bolstered by minute attention to structure. His larger paintings can resemble friezes, with tight, almost rhythmic arrangements whose ingenuity is often concealed by their elegance. He nearly always painted from life, with the exception of his series depicting a lion attacking a horse. At MK Gallery, an example from 1763 has the horse rear up in desperate terror as the lion tears a chunk out of its back. It is difficult not to empathise with the horse.

This emotive side to Stubbs is the final key to his genius. If not quite anthropomorphic, his subjects show comprehensible, unmistakable personalities. In the prancing Whistlejacket (c1762), a horse becomes a majestic symbol of liberty, eyeing its beholder with complicity. The quieter Two Horses Communing in a Landscape, painted sometime before 1777, has a pair of mature horses standing calmly together as if conversing. In Mares and Foals With an Unfigured Background (1762), painted on the same non-representational honey-gold field as Whistlejacket, two foals suckle their mothers in a tender gesture. This expressiveness marks Stubbs as a something of a Romantic, several decades before that movement’s pomp. His combination of minute observation and emotional personalities make his animals vividly alive, like few before or since.

[image4]

The MK Gallery begins before Stubbs’s heyday. His background and early works show just how unusual he was. His father was a Liverpudlian leather-worker, and Stubbs had none of the formal education expected of his contemporaries. Instead, at the age of 20, he moved to York where he made a living as a portraitist while studying human anatomy at the county hospital. His was an art learned from the inside out. One of his earliest surviving sets of work are the illustrations for Dr John Burton’s Essay Towards a Complete New System of Midwifery (1751), for which he drew harrowing pictures showing foetuses in the wombs of women who had died during pregnancy. To see them, it is likely that he had engaged the services of a grave-robber. A contemporary noted Stubbs’s “vile renown in York”.

Given this informal training, it might be surprising that Stubbs never mastered painting people. It is not that he could not, when the occasion demanded. An early double portrait of his patrons Sir Henry Nelthorpe and his Second Wife, Elizabeth (c1746) is competently observed, in a lush, late-baroque style. Later on, with his mature undemonstrative neo-classical manner, he painted Soldiers of the 10th Light Dragoons (1793) as three comically blank toy soldiers, humourless handmaidens to the exercise of military power; perhaps he could have been a wry newssheet satirist.

[image5]

It seems that Stubbs simply did not find people so interesting to paint. With some exceptions, people are almost always secondary in his work, as reflected in his process: he would paint the horses first, adding people and landscapes afterwards. A group portrait of the ceramicist Josiah Wedgwood’s family (1780) includes four characterful, individualised, differently posed horses. The ceramicist’s children are like lifeless dolls. Wedgwood would justifiably complain to friends about Stubbs’s gremlin-like renditions of his youngest pair.

[image7]

Stubbs’s humans come most alive in their relationships with animals. Consequently, his best are often grooms, servants and jockeys, those liable to have the best understanding of their animals. The central hall of MK Gallery provides an inventory of these connections. One from 1761 shows the Duke of Ancaster’s stallion Blank – named such for his undistinguished racing record – held just barely at bay, his lively character brought to heel by a groom. A Turkmen horse belonging to the same duke instead appears placid and calm in the hands of his handler, dressed in Turkish costume to match his charge (c1763-4).

Although the horse would remain his métier, in the 1770s Stubbs began accepting commissions for portraits of prized dogs, which he elevated to a grandiosity usually reserved for their owners. An unnamed water spaniel (1784) looks thoughtful, while the pointer Phillis (1772) is cautious and alert, in a stance that indicates the presence of a game bird. While many of Stubbs’s animals were used in hunting or racing, he almost never painted them in action, but rather in the moments before, charging his work with a sense of expectancy. The dramatic A Cheetah and a Stag With Two Human Attendants (1765), which contains two of Stubbs’s finest human figures, sees the stag consider, with grave alarm, the cheetah about to be released (in the end, the stag flipped over the cheetah with its horns and left unscathed).

[image6]

Stubbs lived in an era where non-European animals were routinely brought to Britain from colonial expeditions, and he captures the wonderment these “exotic” beasts would have inspired. His Rhinoceros (1790-1), which supplanted Albrecht Dürer’s armour-plated monster, has a soft face and blushing pink folds. More extraordinary still is Tygers at Play (c1776) , which shows two leopards lolling about, looking at their viewer as if to announce the startling fact of their existence. Stubbs’s evident delight in, and respect for, animals seems especially pertinent in our era of extinction. It is hard to imagine a time when Stubbs’s combination of flesh and feeling loses its power to startle.