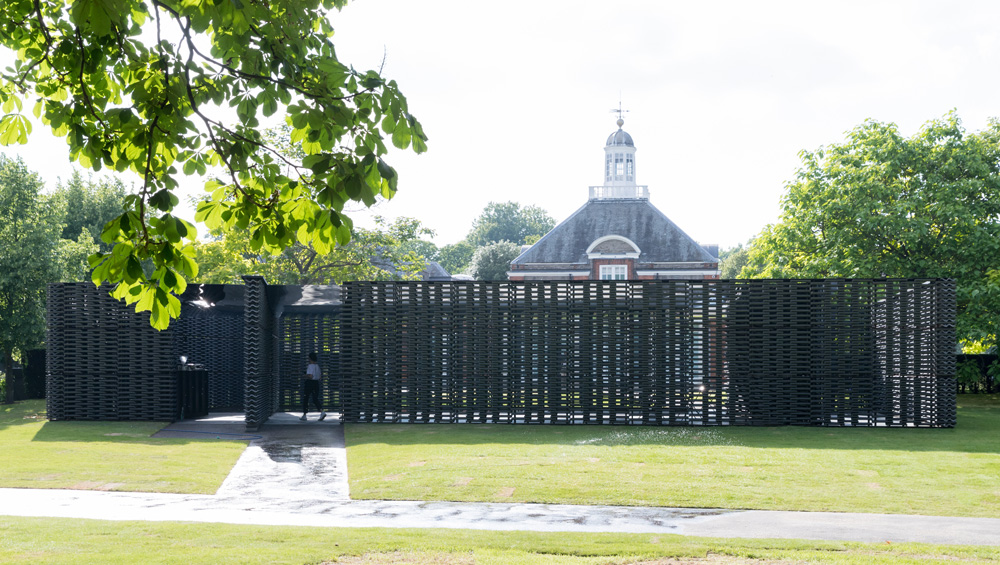

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine Pavilion 2018. Photograph: Iwan Baan.

Serpentine Gallery, Hyde Park, London

15 June – 7 October 2018

by VERONICA SIMPSON

What’s the point of the Serpentine Pavilion? It launched as a showcase for contemporary architecture in a country that seemed to be collectively allergic to the idea back in 2000, when former Serpentine director Julia Peyton-Jones dreamed it up (launching it with Zaha Hadid’s angular, white Marquee, just a few years after the city of Cardiff rejected her competition-winning Cardiff Bay Opera House proposal). Now that fear of the modern and edgy has been reversed (in London, at least): there are towers by Frank Gehry and Bjarke Ingels Group sprouting in Battersea, schools and swimming pools by Hadid, a 65-metre-tall, £750m glass and plastic “crystalline cube” of a US embassy by Kieran Timberlake in Vauxhall, and a City shopping mall by Jean Nouvel abutted by skyscrapers from Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, Norman Foster and Rafael Viñoly.

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine Pavilion 2018 sits quietly in its surroundings. Photograph: Veronica Simpson.

But as resistance to the tenets and aesthetics of modernism recede, there are other, subtler qualities of contemporary architectural practice that still have need of a platform. In fact, the more crammed with status skyscrapers London gets, the more we need pavilions in the vein of last year’s simple, light-touch, tree-like structure by the Burkina Faso and Berlin-based architect Francis Kéré and this year’s gentle sequence of perforated screens by Mexican born and based architect Frida Escobedo (b1979).

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine Pavilion 2018, interior view. Photograph: Iwan Baan.

Escobedo has gone for the cheapest of materials – concrete roof tiles, easily sourced and replicated. British made, these pleasingly rough-edged, dark grey, crenellated forms are stacked on thin steel bars, creating something very like the traditional like the traditional, lattice-like, patterned blocks you find everywhere in Mexico called Celosías.

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine Pavilion 2018. Exterior detail with Serpentine Gallery in the background. Photograph: Veronica Simpson.

The rippling lines, fractal repetitions and abrasive edges sit sympathetically in Kensington Gardens’ green landscape, communing easily with the rough texture of nearby tree trunks, as well as the perforations and light through surrounding tree canopies. Viewed from outside, it has a quiet, calm, reflective presence, with an interior that replicates these qualities, but adds a sense of drama and delight. Inside, the glimmering of light through the latticework walls on to the dark, concrete floor is distorted and reflected in mirrored panels that line the curving underside of its roof, as well as a shallow, 5mm-deep triangular pool where the canopy falls short of the perimeter wall.

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine Pavilion 2018, interior view showing the reflective ceiling of the canopy. Photograph: Veronica Simpson.

The simplicity of it – providing shelter, shade and a sequence of courtyards – replicates the sequential layering of Mexican architecture, which accommodates and adapts to whatever social demands might be made of it. Arranged with its outer walls aligned to the gallery’s eastern facade, the north to south axis connects it – deliberately – to the Prime Meridian, established in 1854 at Greenwich; a discovery that Escobedo has said “defines how time is measured globally”. This gesture thus pins the pavilion in both time and place, in relation to the city and its setting, as well as its era.

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine Pavilion 2018, interior view. Photograph: Iwan Baan.

Time is something that fascinates Escobedo, “not as a historical calibration but rather as a social operation”, she has stated. She is a fan of the French philosopher Henri Bergson and his notions of “social time” – time as social units through which we understand our environments; Bergson also believed that mental and spiritual elements of human experience were being overridden by the 20th century’s overwhelming focus on science and the material realm. Escobedo has responded with a structure that provides it all: material delight as well as spiritual, physical and mental solace.

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine Pavilion 2018, detail. Photograph: Iwan Baan.

Escobedo is only the second solo woman to receive a Serpentine commission; she was chosen by the Serpentine Gallery’s chief executive, Yana Peel, and its artistic director, Hans Ulrich Obrist, on the advice of the architects David Adjaye and Richard Rogers. It’s the same team that chose Kéré last year, and indicates a new spirit, moving away from the big names towards more fluid and experimental figures. Escobedo, however, is no novice – having founded her practice in 2003, her designs have appeared at two Venice Architecture Biennales (2012 and 2014) and pavilions constructed in Lisbon (Architecture Triennale, 2013), Chicago and Stanford. Her biggest scheme to date was the conversion of Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros’ workshop into a museum, La Tallers Siqueiros, in Cuernavaca (2012). And although her studio is small, she is working on a social housing project in Mexico and the transformation of a late-19th-century building into a hotel for the Mexican group Habita, for whom she had previously reinvented the 1950s Hotel Boca Chica in Acapulco into a Technicolor party hub.

Frida Escobedo’s Serpentine Pavilion 2018 disappearing into the landscape. Photograph: Veronica Simpson.

The Pavilion commission has certainly brought attention and favour to those it has invited to this fragrant spot: many whom had never worked in the UK before are now mainstream names, although some have yet to receive a UK project (SANAA). On the strength of Escobedo’s offering, we must hope that the openness, simplicity, artistry and respite offered by her pavilion become qualities that percolate into the wider architectural and urban landscape of UK cities.