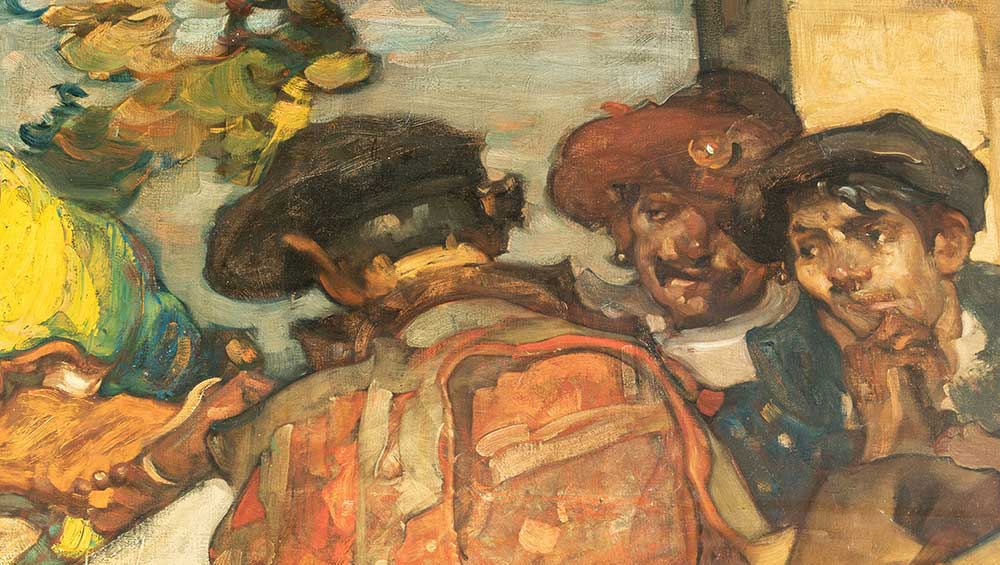

Frank Brangwyn, Founding of Tonbridge School. Oil on canvas. Banqueting Hall of the Worshipful Company of the Skinners, London. Photo: Worshipful Company of the Skinners.

Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft, East Sussex

26 May – 16 October 2022

by BETH WILLIAMSON

You might wonder why a museum in the rural village of Ditchling in East Sussex would host an exhibition of work by the Belgian-born Welsh artist Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956). Brangwyn bought a house in Ditchling – The Jointure – in 1917, although he retained his London residence. It was not until after his wife’s death, in 1924, that Brangwyn established a studio at The Jointure and began to live in Ditchling. He worked in a wide variety of media from painting and drawing to furniture and ceramics, as well as stained glass, woodcuts and book illustration. This is not surprising when you learn that he was, at one time, apprenticed to William Morris (1834-96), a key figure in the Arts and Crafts movement. Brangwyn was best known for his murals, including the British Empire Panels (1925-32), which were rejected for the House of Commons and are instead housed in Brangwyn Hall in Swansea. He was commissioned by JD Rockefeller to produce four large murals for the RCA building, the centrepiece of the Rockefeller Plaza in Manhattan, New York (1930-34). Earlier mural commissions included the panels painted for the Banqueting Hall of the Worshipful Company of Skinners in London (1902-12). It is these panels (currently displaced while Skinners’ Hall is refurbished) that feature in the exhibition at Ditchling.

Frank Brangwyn, Charity. Oil on canvas, 289.6 x 152.4 cm. Banqueting Hall of the Worshipful Company of the Skinners, London. Photo: Worshipful Company of the Skinners.

The enormous Skinners’ Hall murals, usually hanging on the upper wall above oak panelling, stand at more than 2.5 metres (8ft) high. Brangwyn was awarded the original commission in 1902 and did not complete the work until 1912, much later than expected. Two further panels, Charity and Education, were commissioned in 1912 and were finally painted from his Ditchling studio, taking him 25 years to complete. This further local connection is what lends interest here, especially when you realise that he used local villagers to pose as models. In archival film footage, on show in the exhibition, the actor Donald Sinden (1923-2014) recalls his childhood part as one of Brangwyn’s models while growing up in Ditchling.

Frank Brangwyn, Education. Oil on canvas, 289.6 x 152.4 cm. Banqueting Hall of the Worshipful Company of the Skinners, London. Photo: Worshipful Company of the Skinners.

The mural panels themselves are rather overwhelming when seen at eye level within the confines of the tiny Ditchling museum – it is not the setting they were intended for after all and they span the entire space from floor to ceiling. If I am honest, I found the preparatory drawings and sketches for the murals easier to engage with. Study for a mural – Pelts and Furs at City Mart before the Charter (c1902) is an exquisite chalk and ink sketch, much gentler on the eye than the crushing panels beside it. However, this is a rare opportunity to see the murals up close and the themes they depict relate to key moments in the history of the City of London livery company then associated with the trade in skin and fur and now supporting schools as an education charity. In relation to the panel Education (1912-37), we are told that Brangwyn’s requests for models were noted down and pinned up at the village crossroads by his housekeeper, Lizzie Peacock. It is one such request that took the young Sinden and his brother, Leon, to pose for Brangwyn and appear in this panel. I really appreciated these local details. Almost all the photographs of Brangwyn show him wearing a hat and carrying a cane. The same hat and cane are displayed in the exhibition, which could have been entirely uninteresting had the hat not displayed traces of the red chalk Brangwyn used and presumably transferred from his fingertips – another fascinating tiny detail.

Frank Brangwyn, Founding of Tonbridge School. Oil on canvas. Banqueting Hall of the Worshipful Company of the Skinners, London. Photo: Worshipful Company of the Skinners.

A small display of Brangwyn’s pots caught my attention in this exhibition. A collector of ceramics, he amassed more than 600 ceramic pots from Iran, China, Japan, Korea and elsewhere. His interest came initially from his encounters with William Morris and others, such as the ceramic designer William de Morgan. The pots often appeared in his paintings, too. On display in this exhibition are several ceramics design by Brangwyn, including an octagonal serving dish designed for Royal Doulton in 1930 and two pottery jugs designed for Ashtead Potters in about 1929.

Returning to local detail, I was delighted by the inclusion of a small display of artworks by some of Brangwyn’s neighbours in Ditchling. Charles Knight (1901-90) lived in Beacon Road, Ditchling from 1934 and was later an official war artist on the Recording Britain scheme. Ethel Rawlins (1880-1940) settled in Ditchling in the 1920s and made illustrations for The Studio Magazine. Edward Johnston (1872-1944) designed the iconic typeface for the London Underground while in Ditchling in 1913. Amy Sawyer (1863-1945) moved to Ditchling in 1897 and taught art in the village. The artist Louis Ginnett (1875-1946) moved with his family to Ditchling in 1919. There are portraits and interiors by Ginnett, watercolours and woodcuts of Ditchling by Rawlins and Sawyer. All this seems to give a sense of Ditchling as an artistic community. How much that meant to Brangwyn, apparently a recluse in later life, is difficult to say. Still, the fact that you can walk around the village and still see the outside of some of these locations, including The Jointure Studio that was once Brangwyn’s home, makes this exhibition all the more poignant.