Michael Werner Gallery, London

23 February – 11 May 2024

by JOE LLOYD

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) is the patron saint of stylistic disunity. He trained in Paris’s École des Arts Décoratifs, then devoted himself to meticulous historical paintings, but had his first breakthrough as an Alfred Sisley-inspired impressionist. He rose to prominence with scintillating works of orphic cubism, with shapes dancing around the canvas, then spent much of the first world war painting anthropomorphic machines. He joined dada, then renounced it. He befriended Breton, then repudiated him. In 1925, he returned to figurative painting; by the end of his life, he had returned to abstraction.

The mutability of Picabia’s output saw him relatively neglected following his death; his first full North American retrospective was held at the Museum of Modern Art in 2016. Picabia himself did believe there were some central consistencies to his approach. He claimed in his Manifesto of Good Taste (1923) to “aim for a painting which I hope will never be understood as an -ism, but which will simply be a Francis Picabia painting”. It is uncertain whether he achieved this aim. There is one body of work that remains constant throughout the contortions of his long career: drawings of women. Almost fifty of these works now adorn the walls of Michael Werner, drawn from almost 50 years of Picabia’s artistic practice.

[image2]

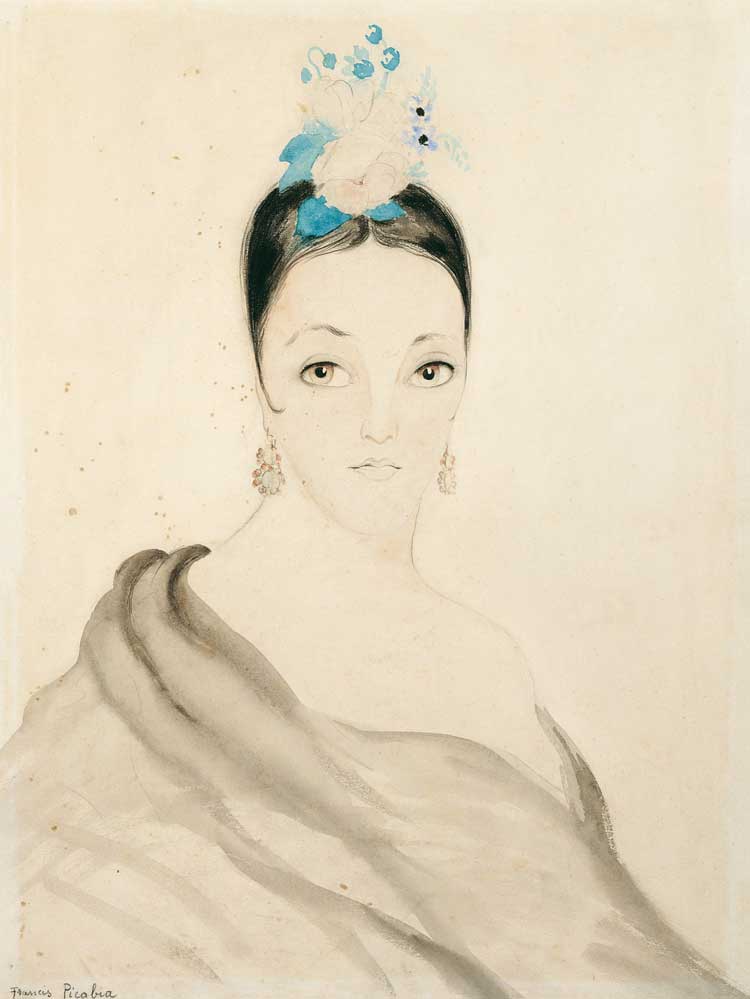

The earliest is a watercolour and ink drawing of a woman’s head from c1902. Picabia captures the softness of her skin in white and faint pink, managing to achieve a depth with the most minute materials. Her black hair similarly attains texture using the sparest of means. The feature that stands out, however, is her eyes, which appear to loll in different directions. Uneasy eyes are a recurring feature of Picabia’s drawings. In the Portrait de Méraud Guinness (c1928), a jocular expression is counterbalanced with eyes that seem half-guarded, uncertain of the man sketching them. An Untitled (Portrait de femme) (c1932-38) shows a woman awkwardly lean on an invisible armchair. Although her eyes are rendered using pencil and negative space alone, they emanate an amused confidence.

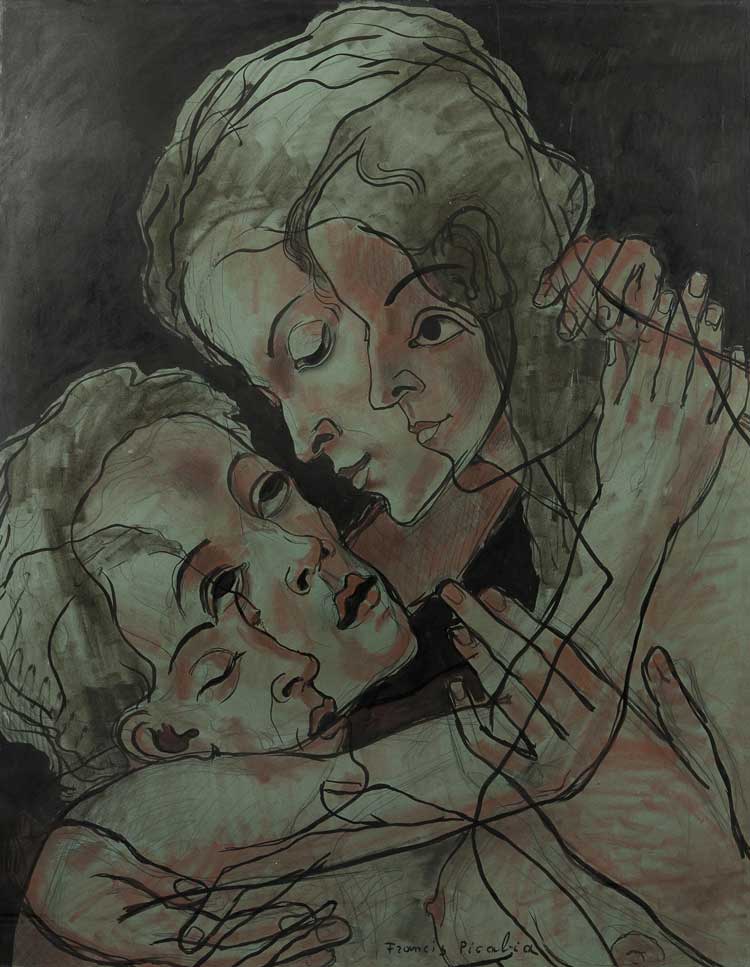

The straightforwardness of these drawings often contrasts with the strangeness of Picabia’s concurrent paintings. But there are some close connections. Quadrilogie amoureuse (c1932) is a drawing in the mould of Picabia’s Transparencies paintings (1927-32). These gnomic works appear to superimpose multiple images atop each other, including figures from old master art, flora and apparently abstract lines. Quadrilogie amoureuse is a comparatively simple application of this process, with two pairs of lovers overlapping as they reach to embrace. It is sensual and a little comic at once, as the amorous couples intermingle to create a blur of flesh.

[image3]

An entrancing set of four mid-1920s watercolours of women in Spanish lace mantillas also connects to the transparencies, some of which (such as Espagnole et agneau de l’apocalypse, c1927-28) centre on similar characters. Picabia had a Hispanic-Cuban father and spent part of the war in Barcelona. These pictures appear to draw on his memories and the early 20th century vogue for Spanish exoticism, as epitomised by Maurice Ravel’s music and Ernest Hemingway’s novels. Picabia’s Espagnoles are women and characters in a fictitious melodrama. They are a world apart from the dadaist avant garde he had belonged to just a few years before.

[image5]

Picabia could rapidly flit from high art to popular culture. As the curator Sara Cochran writes in the exhibition’s catalogue: “Picabia had always produced work that looked avant garde at the same time [as] he made work that was considered anachronistic and even tawdry.” In the late 1930s, he started painting and drawing images borrowed from and inspired by French glamour magazines. The bulk of the pieces in Michael Werner’s ground floor gallery date from this era. Some depict Hollywood stars, some friends, and some are anonymous. A pencil and gouache portrait of Carole Lombard (c1941-42) features similar subtle contouring to the 1902 head, recreating the actor through the sparest of means.

[image4]

Other works evoke parallels between the facial expressions of magazine models and those in Renaissance paintings. Picabia’s women often seem bathed in holy light. As in the earlier works, it is frequently the eyes that pull attention. Here they are often mediated through layers of makeup, lashes and painted brows. A c1933-34 pencil portrait of Greta Garbo sees her gaze out blearily through a gauze of smudged eyeshadow, inert as a statue. A c1940-42 return to Garbo, by contrast, catches her piercing and wide-eyed. Picabia studies an actor’s ability to transform their face.

There are questions to be asked about the artist’s gaze over these women. Picabia was an inveterate playboy. According to his second wife, Olga Mohler, he had owned seven yachts and 127 cars. Stories circulated in which he eloped with critics’ wives and stole brides on their wedding days, a real-life Don Juan. An uncomfortable series of later works show the artist as a dirty old man. There is an untitled (c1949) ink sketch of a nude from behind. Her buttocks are decorated with two eyes and a full set of male genitals. A set of four thicker-lined ink drawings (c1949-50), deft and simple, show another nude woman, in one instance without a head, spread her legs.

[image8]

The public image of Picabia as a “dangerous and disruptive” figure soon became a parallel to his art. Writing a preface for a 1946 exhibition, René Magritte recounted amorous anecdotes from Picabia’s youth to explain that his life and work aimed to restore pleasure to a war-torn world. Yet by focusing on the posed stars of magazines, he may also be calling attention to the artifice of such staged images, created as fantasies to ameliorate the present brutality. As so often with Picabia, the answer remains elusive. But the pictures themselves have a startling directness.