Blain Southern, 4 Hanover Square, London

30 November 2012–26 January 2013

by Dr JANET McKENZIE

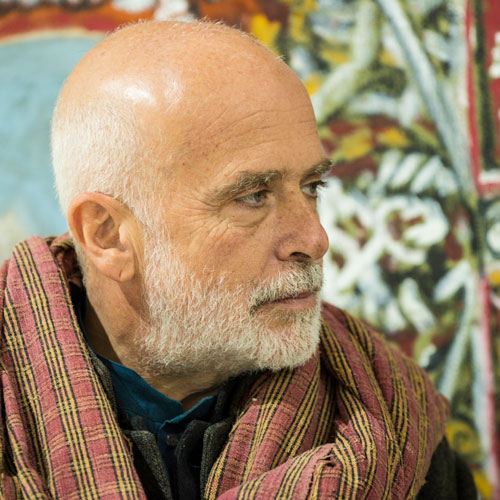

His work is the product of a libertine, a freethinker in spiritual matters: it celebrates the unknowable in life. A combination of self-scrutiny and an insatiable appetite for culture and ideas, Clemente’s diverse imagery is at once solemn, inspiring and hopeful. Recurrent themes elicited from meditation and dream sequences, quotidian experience and literature, have enabled the creation of a lexicon of images that might appear fragmented but in fact provide a transcendent path to a cohesive concept of self.

Clemente produces works of great elegance and originality; he also imbues them with tenderness and humour, referencing abiding images from literature, poetry and art history. Raymond Foye observes the nature of Clemente’s oeuvre: “It is a visual synthesis of diverse and complex elements that form an hermetic system, impervious to theory or logic, yet open to multiple definitions. And by its indivisibility the image posses a oneness that in centuries past was the province of divinity”1

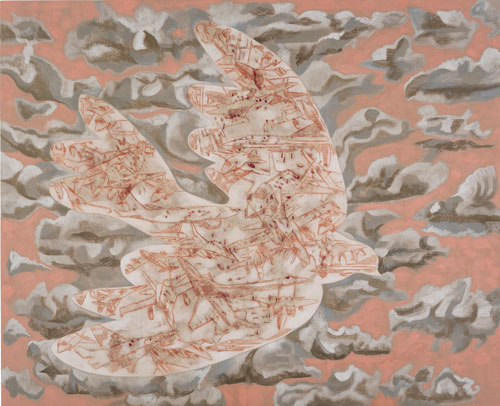

Mandala for Crusoe, the current exhibition at Blain Southern’s new gallery in Hanover Square in London, is a unique body of work, for its esoteric and enigmatic use of symbol and visual narrative. They allude to everything from Thomas Carlyle’s Victorian culture to American movies. In Indigo’s Child, a black stallion is standing against the night sky, ejaculating gold and spewing it from its mouth, over a Reclining Venus. Titian’s Dänae, in which Zeus impregnates the imprisoned woman, is the obvious reference but Clemente’s classical myths are never literal, combining mythical narrative with dream images. If Zeus becomes the horse then the birth of a fully- grown male, from the horse’s body is not entirely unexpected in this, the artist’s misè-en-scene. Birds for all their manifold symbolism proliferate in Clemente’s work, as they did for Picasso, Braque, Ernst and Magritte. Clemente adds aeroplanes, zooming into the symbolic equation, in The Dove of War, generically technical in the manner of his fellow countryman, Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005) whose family settled in Scotland from Italy in the early years after World War I. As scores of backpackers march quietly over a cliff in the highly amusing work: The Backpacker, the artist’s playfulness, derides mass tourism and the paucity of global culture. The artist’s despair is vented here at the mindless, devalued consumerist approach to world culture. “Clemente exhorts us to take our experiences from everywhere. But as a Westerner he especially wishes us to absorb as much as we can from Eastern wisdom”.2

Francesco Clemente was born in Naples in 1952, and was part of the Neo-Expressionist painters of the late 1970s: La Transavanguardia: with Sandro Chia, Enzo Cucchi, and Mimmo Paladino. He had first studied architecture at the University of Rome, exhibiting drawings, photographs and conceptual works from an early age. In 1973 he made his first trip to India, and has travelled there regularly since. In 1981 he moved to New York. At a time when conceptually-based art dominated, Clemente’s art was skillful and painterly; where Arte Povera had asserted process over finished product, using a range of non-traditional art materials, he used watercolour, pastel, with consummate skill. Frescoes pay homage to medieval and Renaissance Italian art, and its pivotal position in Western art history and civilization.

In 1993, Francesco Clemente: Three Worlds, the exhibition of works on paper from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (October-December 1990) was shown at the Royal Academy, London. Organized by Ann Percy, Curator of Drawings, the show was meticulously curated with a scholarly catalogue. Known for its research in contemporary drawing and its collection, the Philadelphia Museum also in 1993 produced in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art, New York: Thinking Is Form: The Drawings of Joseph Beuys. These remarkable exhibitions show the role played by drawing in the practice of Francesco Clemente and Joseph Beuys, so to be examined and subsequent works to be better understood.

In Three Worlds, the works on paper done in Italy, India and New York can be seen to have provided Clemente with method, conceptual framework and imagery to sustain a lifetime. Drawing here is broadly defined, and inclusive of a range of materials. Mark-making of a subconscious nature, perceptual drawing such as portraiture of friends, and the colour drawing, which can be compared in terms of liberating practice to that of Helen Frankenthaler in the 1960s in New York, all play a part in the orchestration of ideas, feelings and spiritual states. An elusive lightness of touch, which runs through his oeuvre, can only be achieved with the skill acquired over decades of experimentation and practice. The notion too, of ‘lightness’, delicacy or luminosity: physically and as a metaphor enables the sacred and profane to inhabit the same picture plane. Lightness is Clemente’s “main strategy for getting out from under the weight of tradition, formalism, ideology – all of the accepted and received suppositions with which we are burdened”.3 A love of materials drives experimentation with and the harnessing of the intrinsic qualities of each, pastel being of his finest.

Although traditionally a relegated medium in terms of the hierarchy of the arts, pastel has been used by many artists historically and in a contemporary context as a testing medium, for the exceptional qualities of combining pure pigment with the drawn line. In fact, many artists, historically and in contemporary art practice, use it in periods of transition and experimentation, to convey ideas with immediacy and directness, to express the permutations of light and tone. The French historian, Geneviève Monnier in: Pastels from the 16th to the 20th Century (Skira, 1984) describes pastel as:

Powdered colour with an infinite range of shades and gradations, of unfading freshness and intensity, spanning more than 1650 nuances of the colour spectrum, and peculiarly fitted for ease and rapidity of handling, immediate transcription of an emotion or idea, easy effaced, easily reworked and blended. The pigments can be rubbed in, made luminous and velvety, or given a soft and silky mattness of grain. Pastel is line and colour at once. It can also be built up into rich skeins of blended lines, into rapid jottings of all colours creating a dense and brilliant texture.4

When Clemente returned to Rome after his first trip to India, he was challenged to inform his work with the cultural multiformity of India, in contrast to the cultural hegemony of the West. He stated: “My overall strategy or view as an artist is to accept fragmentation, and to see what comes of it – if anything… Technically, this means I do not arrange the mediums and images I work with in any hierarchy of value. One is as good as another for me. All the images have the same expressive weight, and I have no preferred medium…. I believe in the dignity of each of the different levels and parts of the self. I don’t want to lose any of them. To me they each exist simultaneously, not hierarchically…. To lose one is to lose all”.5

Drawing, or mark-making, as the most direct form of expression, is an appropriate means of traversing the critical storms and culs-de-sac that have created barriers for the comprehension and enjoyment of much contemporary art. Drawing has been described by the poet Seamus Heaney as an art form that occupies a, ‘placeless heaven,’ freed from the literal.

Drawing is closer to the pure moment of perception. The blanknesses, which the line travels through in a drawing, are not evidence of any incapacity on the artist’s part to fill them in. They attest rather to an absolute and all-absorbing need within the line itself to keep on the move. And it is exactly that self-propulsion and airy career of drawing, that mood of buoyancy, that sense of self-sufficiency in the discovery of a direction rather than any sense of anxiety about the need for a destination, it is this kind of certitude and nonchalance which distinguishes the best of Kavanagh’s later work also.6

(Seamus Heaney, excerpt from his essay ‘The Placeless Heaven’ on the poet Patrick Kavanagh in Finders Keepers: Selected Prose, 1971-2001). Heaney’s own career as a writer is constantly informed by the questions that artists also address in their work, “How should artists or writers live and create? What is the relationship between art practice, and art objects; between the creative act and the artist or writer whose voice informs it; one’s literary heritage and the contemporary world? Likewise Thinking Is Form, expressed Beuys’s conception of the processes of drawing and making sculpture as profoundly akin to thought, connecting subjective experience and conceptual thought in single act.

Drawing is the first visible form in my works… the first visible thing of the form of the thought, the changing point from the invisible powers to the visible thing…It’s really a special kind of thought, brought down onto a surface, be it flat or be it rounded, be it a solid support like a blackboard or be it a flexible thing like paper or leather or parchment, or whatever kind of surface…It is not only a description of the thought… You have also incorporated the senses… the sense of balance, the sense of vision, the sense of audition, the sense of touch. And everything now comes together: the thought becomes modified by other creative strata, within the anthropological entity, the human being… And then the last, not least, the most important thing is that some transfer from the invisible to the visible ends with a sound, since the most important production of human beings is language… So this wide understanding, this wider understanding of drawing is very important for me.7

Clemente met Joseph Beuys in Naples in 1974, where Beuys had held his first Italian exhibition in 1971; in 1980 Beuys returned to the city after the devastating earthquake took place to take part in relief work. In Naples, he made the remarkable work Tomb (1985), a shamanistic work one year before he died. Beuys was, of course, essentially political and Clemente is not. What Clemente responded to in Beuys’s art was according to Ann Percy, “an artistic intent that seeks to retrieve and revive lost and forgotten elements of common human experience or consciousness in order to move people away from their material, rational selves and back to their more mystical or spiritual ones. This intent legitimizes for Clemente the reasons for becoming an artist. Both Clemente and Beuys have made use of the medium of drawing as a way of thinking that connects earlier to later works and links all aspects of their oeuvres, and both have produced great quantities of drawings, using them as part of a regenerative process and as a reservoir of basic source material”.8

Clemente’s Three Worlds: Italy, India and New York have all contributed to the range of imagery (Classical literature and philosophy, meditation and Buddhism, Beat poetry albeit read in Italian translation before moving to the US – respectively) that is at times disconcerting. Locale determines the work too in terms of materials and methods. What is constant is the human form, pitched against both new and comfortably familiar environments to define and redefine the human condition through individual identity and dialogue.

Clemente’s drawing underpins his diverse practice from the small ink on paper notations in the 1970s, to thousands of gouaches, charcoal, pastels, watercolours, etchings and lithographs, over three decades. Over time his drawings also became larger, joining sheets of paper together. He collaborated with Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat; with the poets Allen Ginsberg, René Ricard, Robert Creeley, and John Wieners. He particularly admired Jack Kerouac and Beat poets: “They were guides for any artist whose innermost fears and joys were the prime area of artistic exploration.”9 The Beat poets also embraced Eastern thought. Kerouac was raised Roman Catholic but went to India and immersed himself in philosophy and religion there. The true artist in this context did not impose formal boundaries or systems but allowed thoughts, emotions and perceptions for inspiration. In the process reason and societal values could be rejected. Further, Eastern philosophy allowed everyday experience equal of validity or importance as the sacred.

Ezra Pound’s The Canto (1917-69) shares Clemente’s yearning for unity in all aspects of life. His affinity for a peripatetic life enables him to straddle Eastern and Western traditions, yet he works within the Italian painterly fresco tradition, albeit on large canvases. By electing to exile himself- from the overblown commercialism of western society, Clemente can identify with Daniel Defoe’s fictional character, Robinson Crusoe (1719) shipwrecked in isolation, thus precipitating a reliance on self and in turn personal revelation. For Clemente the castaway is not a hero but an Everyman whose disobedience (like the Biblical story of Jonah) is punished at sea, which is in turn a metaphor in literature for the spiritual journey of life. Crusoe does not find God through organized religion but through Nature and solitude.

Mandala for Crusoe, the new series of 14 paintings is inspired by the symbolism of the originally Buddhist and Hindu Mandala. Mandala is the Sanscrit word for circle; in Buddhist and Hindu traditions, sacred art often uses the mandala form of a circle within a square. In common usage it refers to metaphysical observation of the human condition. The mandala is central to anuttarayoga meditation. It can be seen as a designated spiritual entity, a place out with quotidian concerns, the psychological chaos of technological and media overload. Yet the centre of Newspaper Mandala contains the not the Buddha or a void, but the outline of a man reading a newspaper. In Sound Bites Mandala, he gazes at a mobile phone, perhaps making reference to the intense difficulty of the spirit to be adequately nourished in the present. “Is this the new path to Nirvana?” Norman Rosenthal asks in his essay ‘Crusoe Meets Clemente’.10

As sage or mediator Clemente here asserts opposites such as the sublime and the ridiculous as a plea to break down artistic and religious hierarchies. In contrast to the muted palette of the 14 large paintings in the Blain Southern exhibition, the colours in the mandala paintings are both richer and deeper, and have the quality of Oriental carpets, or magical gardens. The symbolic configuration of the mandala, in meditation (or viewer in the case of the art works), enables access to deeper levels of consciousness. Clemente’s work leads the viewer to a plane of greater meaning, enabling a mystical oneness with creation. Unlike Biblical narrative, which informs the strict liturgy of Roman Catholicism, the mandala enables the cosmos to be contemplated in its manifold forms. In psychoanalysis, Carl Jung viewed the mandala as, a representation of the unconscious self. He believed that paintings of the mandala enabled the identification of mental disorders; in Jungian terms the mandala is the symbol of the perpetual effort to reunify the self.

Rosenthal observes: “The effect of losing the self is surely the goal of all artistic endeavor; the product too of listening to music, reading literature and contemplating painting. [Clemente’s paintings] are emblematic in the best sense, enabling us to be enveloped in a subjective world of the imagination in which we are absorbed by the artist’s endlessly stimulating narratives.”11 In the context of Mandala for Crusoe, Clemente offers a structure for himself, and his audience, to come to terms with the cultural and spiritual chaos of modern life. Isolated within heavily populated cities with the world apparently bent on environmental disaster, the artist as sage offers the teaching aspects of the mandala as a path out of the complex map of the contemporary world. His imagination, like that of William Blake provides the necessary means for us to be nourished to that end.

References

1. Raymond Foye, “New York”, Francesco Clemente: Three Worlds, by Ann Percy and Raymond Foye, with essays by Stella Kramrisch and Ettore Sottsass, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1990, p.125.

2. Norman Rosenthal, “Crusoe Meets Clemente”, in Francesco Clemente: Mandala for Crusoe, Blain Southern, London, 2012, p.13.

4. Geneviève Monnier, Pastels from the 16th to the 20th Century, Skira, Milan,1984, in English MacMillan, London, 1984, p.6.

5. Quoted by Foye, “Madras”, op.cit., p.51.

6. Seamus Heaney, “The Placeless Heaven”, Finders Keepers: Selected Prose, 1971-2001, Faber and Faber, London, 2002.

7. Joseph Beuys, quoted by Bernice Rose, “Joseph Beuys and the Language of Drawing” in Ann Temkin and Bernice Rose, Thinking Is Form: The Drawings of Joseph Beuys, Thames and Hudson with Museum of Modern Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art, New York, 1993, p.73.

8. Ann Percy, “Italy”, op.cit., p.21.

9. Foye, “New York”, op.cit., p. 118.