Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

28 May – 15 September 2019

by JOE LLOYD

Of all the treasures in London’s National Gallery, none leavens my mood on a gloomy morning as much as the five predella panels from the first of Fra Angelico’s altarpieces for the San Domenico monastery in Fiesole (1423-4). In the central panel stands one of the most serene Christs of the Renaissance, clothed only in a simple white toga and with his right hand and two fingers raised. He stands on the gilded background, atop which grooved shafts of light emanate from his body, establishing his divine privacy and shining on the amassed choirs of angels gathered to praise him. The two panels on either side show the assembled ranks of prophets and saints, with two smaller outer panels filled with the most revered among the Dominican monks, aspirational figures for the altarpiece’s monastic audience.

[image3]

I can’t pretend to be able to identify more than a small proportion of the figures present – though it is a fun game to try – but I am transfixed by their individualisation. Although tiny, each saint has different features and distinctive attire, in an astonishingly rich array of patterns and colours. Most look towards Christ, some solemnly, others overcome with joy. A few appear to converse, or to silently catch each other’s eyes in acknowledgement of their shared roles in the dissemination of their faith. Moses gazes outwards, brandishing his tablets as if to remind his beholders of their duty. For all the sacred pageantry of the scene, which might hold the record for the number of gold halos present in a work of art, Angelico’s luminaries feel human.

This summer, these five panels have been hung in the Prado, for the most significant exhibition of Angelico since the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2005 blockbuster. Angelico is not an easy painter to survey. Many of his masterpieces are immobile, painted in tempera on the walls of the San Marco monastery in Florence in the late 1430s and early 1440s. Focusing by necessity on the works of the 1420s that saw Angelico make enormous strides in his use of colour and perspective, the Prado has nevertheless gathered 82 pieces from institutions across Europe and America, largely by Angelico, but also from contemporaries including Donatello, Masaccio and Uccello, as well as his lesser-known tutor, Lorenzo Monaco. It amounts to a precious, sensitive exploration of one of the pivotal transitions in western art history, as the gothic slid into the Renaissance.

[image6]

Angelico was at the forefront of these changes, though to cast him as a Michelangelo-esque firebrand would be to dismiss what we know of his life. He was born Guido di Pietro in the Mugello region to the north of Florence. According to Vasari, Guido’s artistic career began with illuminating books. One of his earliest attributed works in the show, the Vatican’s minute depiction of the young St Anthony meeting a hermit (c1411-14), has all the narrative clarity of that medium. The hermit’s cave is distinctly architectural, like a monastic cell, in a curious prelude of that which was soon to come.

By 1423, Guido was a Dominican friar in Fiesole, and for the remainder of his life he would be nominally based between the monastery there and San Marco in Florence. He took the name Fra Giovanni, and was known outside the community as Fra Giovanni da Fiesole; the Angelico (“angelic”) came after his death, both for his artwork and his character. “It is impossible,” wrote Vasari, “to bestow too much praise on this holy father, who was so humble and modest in all he did and said.”

[image8]

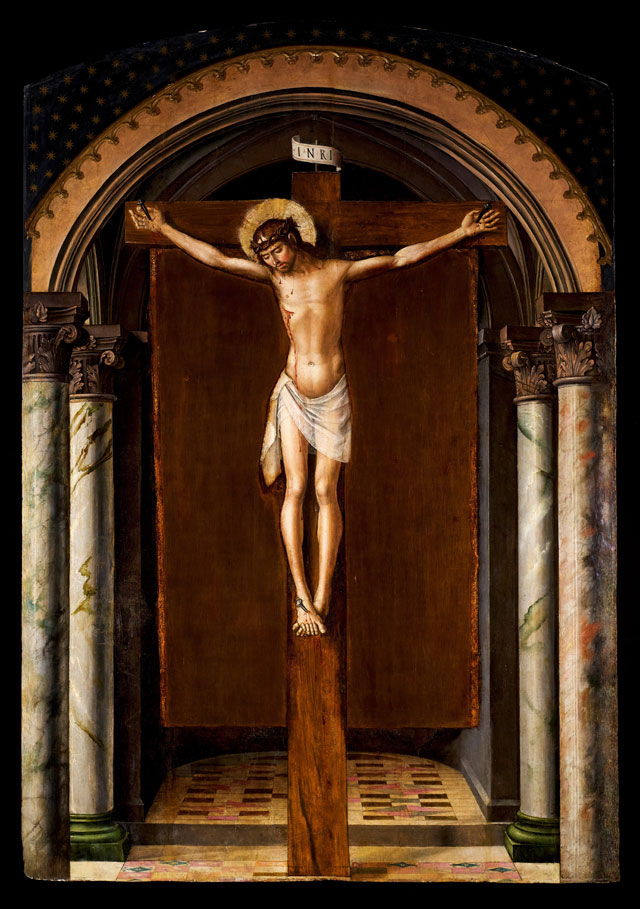

The man described in the Vita more than lives up to this claim. He refused to eat meat, even on the pope’s invitation, without his prior’s permission; he declined the title of archbishop, instead recommending another for the post. “It is averred that he never handled a brush without fervent prayer, and he wept when he painted a crucifixion,” said Vasari. In spite of Angelico’s secluded life and piety – in 1982 he became the only Renaissance artist to be beatified by the Catholic church – he was able to manage a studio and travel to accept work. He died in Rome, the most celebrated artist of his time, probably while working on a papal commission.

[image4]

At the Prado, we are almost immediately witness to the talent that would enshrine his fame. Compare his c1420 depiction of the Virgin and Child surrounded by Angels, now at the Hermitage, with Monaco’s larger, roughly contemporary rendition of the same theme. Monaco, himself a fine painter, has a blue-black robed Mary enthroned front-and-centre with six angels jostling for place behind. Angelico forsakes the chair, and his master’s gothic framing, to show an outsized Mary crouching on an elaborate carpet of red and gold, four rainbow-winged heavenly messengers turned in prayer towards her, beauteous, albeit removed from all sense of scale. Angelico’s Madonna, with her remarkably delicate features and gaze cast beatifically towards her beholder, instils an intimacy with her viewers and understands her own significance as the centre of the story.

[image11]

This ability to jointly instil emotion and drama into well-worn religious scenes only became more pronounced as Angelico’s talents were sharpened. A Crucifixion (c1418-20) from the Met, whose circular composition was probably inspired by Ghiberti’s doors for Florence’s baptistery, places Roman soldiers and the collapsed Virgin in a circle beneath the cross to potent effect, though there is still little artificiality in its two-levelled arrangement.

[image2]

The Virgin of the Pomegranate (c1424-25), acquired by the Prado in 2016, appears self-aware of her own role and the trials that will afflict her innocent son, even as two angels attire her in a golden robe that gleams rather than glitters. While many of Angelico’s contemporaries used gold solely an embellishment, here it becomes another colour, with its own array of textures and hues.

[image12]

Much of the exhibition inevitably serves as prelude to the Prado’s own, newly restored Annunciation and Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden (c1425-26). Painted for the monastery in Fiesole, it represents a great leap forward for Angelico and the Renaissance as a whole. It was the first altarpiece of the Italian Renaissance to dispense with the arched frames of gothic art, with Angelico instead solely rendering architectural space on the panel. And it took perspective, which had been developed by his short-lived contemporary Masaccio, to a fertile new plain.

We encounter Mary in a Tuscan loggia, sparse but for its blue ceiling speckled with stars. An illuminating comparison with the Netherlandish pioneer Robert Campin’s own brilliant Annunciation (1420-25) reveals the boldness of this domesticity. Campin placed his Virgin within a cavernous cathedral, appending Romanesque and Gothic elements to visualise the transition between fallen man and the new reality. Angelico instead uses his structure to ground the scene in the accoutrements of 15th-century life. A sparsely decorated room in the background contains a humble bench and a table.

Angelico’s Virgin sits, arms crossed, with prayer book on lap, as Gabriel delivers the news of her conception. Her palpably warming blue robe, faced with a soft green, falls open to reveal a slimmer lighter pink dress below. This palette is exactly inverted in a gold-winged Gabriel, establishing this moment of accord between heaven and earth. A ray of divine light, shot from the sun by two perfect hands, shimmers translucently towards the Virgin, interwoven with the terrestrial rather than erasing it. Outside, Mary’s sumptuous, verdant garden – a reference to the hortus conclusus (enclosed garden), one of her attributes – is also Eden, as a shamefaced Adam and Eve are shuffled out of frame by their own angel. Man’s fall and redemption are elided into one visual locus.

[image5]

The Prado offers myriad further reasons to marvel at Fra Angelico’s early 1420s work: the delicacy and lifelikeness of his figures, the vividness of his hues, his ability to capture a story in a single scene, all of which develop over time. An equally compelling strand sees chaotic compendiousness give way to orderly compression, and medieval flatness give way to Renaissance depth. The delightful Stories of the Desert Fathers (c1419-20), on a canvas almost three times as wide as it is tall, gathers dozens of biblical stories in a panoramic landscape. Each story is rendered immediate and equal, but they lack individual distinctness, and appear to exist outside time.

By the time of his Stories of Saint Nicholas of Bari (c1437-38), one of the mature works that serve as the exhibition’s coda, Angelico instead creates a linear path through three stories, arranged in an illusionistic architectural ensemble that guides the viewer’s passage from left to right, as if moving through the acts of a play. For all the joys of Angelico’s early paintings, his progression to his abridgement seems especially miraculous. And although it laid the groundwork for much to come – it is difficult to imagine, for example, Piero without Angelico’s example – his marriage between medieval and modern remains one of the peaks of European painting.