Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London

4 March – 17 May 2020 (Following careful consideration in response to the COVID-19 situation, the Serpentine Galleries will temporarily close to the public from 17 March until further notice.)

by VERONICA SIMPSON

The smell is overwhelming: a full-on, feral scent of forest floor, it floods the nostrils, activating memories of tree sap, fresh-cut wood, sawdust; nature both in full bloom and felled. This conflicted mix of associations does much to frame, in fragrance, the provocations in this show, by the Italian design duo Andrea Trimarchi (b1983) and Simone Farresin (b1980), who run their Amsterdam-based design consultancy as Formafantasma.

[image5]

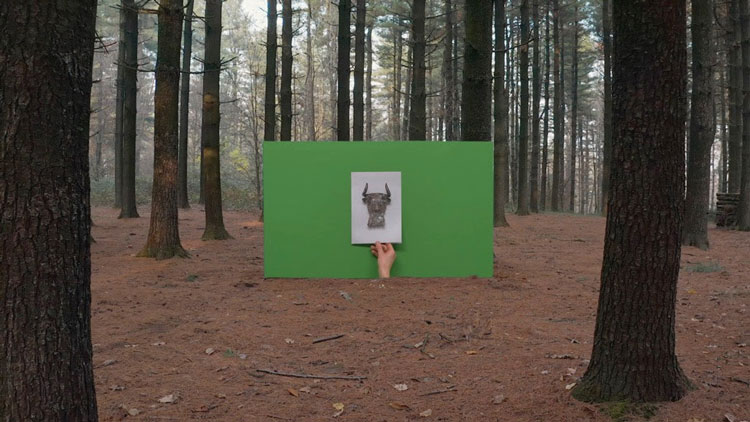

Titled Cambio, from the medieval Latin “cambium”, meaning change or exchange, the exhibition is an uncompromising and stimulating examination of trees, looking at our relationship to them through the ages, but especially in the last 250 years, since the Industrial Revolution. We are invited to admire the tree’s resilience, diversity and magnificence, while, at the same time, our noses are fully – and fragrantly - rubbed in our complicity in destroying this precious planetary resource. Scheduled as part of the Serpentine’s 50th anniversary celebrations, this kicks off the galleries so-called “year of ecological thinking” with a collaborative interrogation of design’s political and environmental responsibilities, via a mixture of film, installation, speculative proposals, sculpture and treasured tree specimens.

As designers, Formafantasma are complicit in the environmental depredation caused by the thriving consumer goods sector. But while conjuring objects of beauty and value for some of the world’s most admired brands – Fendi, Max Mara, Flos, Droog and Lexus, among them - over the last five years or more, Trimarchi and Farresin have begun to research the impacts of this frenzy to fuel and feed consumer desires with the latest products. They took the opportunity of a commission for the 2015 Triennial of the National Gallery of Victoria to research the extraordinarily wasteful and environmentally depleting methodologies by which mobile phone components are sourced and then disposed of, once their short life is over. Ore Streams, as their collaborative investigation was called, continued, with further meditations and responses exhibited last year at the Milan Triennale, in the Broken Nature exhibition.

The subject of this Serpentine show, wood, an everyday material that we all take for granted, brings our depletion of natural resources a lot closer to home. That overwhelming perfume – created for the show by the Norwegian artist Sissel Tolaas – brings the message even nearer, enveloping us, as it percolates every room in the gallery (a very appropriate setting, given that this is a Grade II-listed, 19th-century gunpowder storeroom, a picturesque brick-walled, timber-raftered relic of Britain’s industrial and colonial heyday).

[image3]

It is one thing to inhale that forest scent while looking at two sections of oak tree carcass that sit inside the entrance to the gallery, all sliced, propped and strapped up, ready for shipment in front of a two-screen projection of timber felling, sawing and treatment, but it is quite another thing to be immersed in that scent while watching the films in either of the internal two galleries – the south and north “powder rooms”. In each of these, rustic-chic, chapel-like spaces, their ancient roof timbers beautifully spotlit, highlighting the supporting walls of tactile, exposed brickwork, Formafantasma’s films take us deep into the mystery and magic of the forest. In the South Powder Room, Cambio (2020) is a visual essay on how the timber industry has evolved. The main image on the screen is of a large, antique forest, while, inset, a sequence of images reveals the impacts of exploitation, colonialism and consumerism, in synch with the gentle voice of the female narrator. I sat, riveted and moved, throughout its 23 minutes 21 seconds, on the generous, wooden bench designed by Formafantasma and supplied by the duo’s gallery, Galleria Giustini/Stagetti, Rome.

[image12]

Two presentations inhabit the North Powder Room. On one side is a video, Seeing the Wood for the Trees (2020), which looks at the timber industry’s governance and regulation, highlighting the worst and best practices of tree husbandry and stewardship. The other side of the room is occupied by four reading posts or “lecterns” with screens and headphones, offering direct access to filmed interviews with specialists, as well as information, images and archive material that the artists have gathered over the last 18 months while researching this issue.

[image10]

Arranged along the west gallery that runs perpendicular to the screening rooms, there are collections of maps, some hand drawn by members of indigenous Amazon communities, and digital printouts of various laudable policies and proposals, whose strictures are, it seems, open to interpretation. Displayed in the North Gallery is an impressive range of archived woods, from Kew Gardens’ Economic Botany Collection, some of them relics from the Great Exhibition of 1851, the purpose of which was to incite desire and inspire new products to be made from their often rare and – probably now - endangered tree species. An adjacent video reveals how easily designers can use modern digital tools, such as KeyShot, to specify rare and endangered woods at the click of a mouse from their extensive materials libraries, without a thought for the consequences.

[image8]

The impact of unthinking design transforms into unthinking consumption in the final, East gallery, with a tool shed-style lineup of everyday items, from musical instruments to makeup brushes, arranged along one wall, sourced from a variety of retailers. Below them, a clipboard reveals the origins of the wood used in their manufacture: a small red cube by the clipboard and item flags up if that wood is taken from an endangered species. There are a lot of red cubes; apparently, illegally sourced wood products account for between 15 and 30% of all traded timber items, according to Interpol.

On a nearby table, disposable paper and cardboard products, from reinforced envelopes to paper towels and takeaway containers, are gathered in separate piles, in a display titled 5 Years (2020). The title refers to the number of years it will take for a single pine tree to reabsorb the amount of carbon dioxide that the generation of each pile released.

[image2]

This gallery culminates in a totem pole of stools, inspired by the £20 Ikea Bekväm stool, which Formafantasma has remade in seven different kinds of wood, including chestnut, oak and cherry. The relative proportions of each type of stool indicate how long the tree grew before it was logged, as well as how much carbon dioxide it stored during that growth period.

In an interview I conducted with the designers for Blueprint magazine, in 2018, they said: “We have the power, as designers, to address serious issues if we think bigger, and more collaboratively.” They have certainly expanded their remit with this investigation, bringing in climatologists, wood evolutionists, philosophers and anthropologists. Speaking at the opening, Farresin told me: “We cannot design in a vacuum: design is such a weird thing because it sits at the middle of everything that is about visual culture, but it’s also about social change, also about social justice and injustice and how we produce things. In a way we wanted the exhibition to pull people in all different directions.”

A series of workshops and talks during this show is planned that will hopefully broaden and deepen these debates. It would be easy to be cynical about the fact that Formafantasma’s commercial work continues to fuel this cycle of desire for things we don’t need (not to mention that all the furniture they made for this show will be sold by their gallery), but the fact that they devote so much time and energy to investigating and revealing the scale of the problem – as well as considering how they and their clients could improve the system – is to be applauded.

Is it my imagination or has the scent, as I leave, transformed into something far more like sandalwood, Frankincense, or myrrh – that unmistakable fragrance of Catholic and Orthodox church services? It is the scent of something sacred, also derived from trees. That is a nice, lingering note on which to exit the building.