Design Museum, Shad Thames, London

29 March-10 June 2007

For example, the exhibition opens with some of his very early work, like the very simple metal lampshades, wooden furniture and ceramics designed and made in the 1950s. But nothing is said about how some of this was made at the suggestion of Irvine Richards, who persuaded Sottsass that Italian crafts would sell well in the US (they didn't), nor that the very simple geometrical patterns used on the plates reflected Sottsass's graphics at the time. Indeed, they featured on posters Sottsass did for the 11th Milan Triennale of 1957, for which Sottsass also designed an over-structured stand made of wood covered in silver paper for Italian glassware. The stand had open and closed areas like a magical wood and made up for the fact that there was very little glasswork to show.

In fact, it was this stand that led Adriano Olivetti to invite Sottsass to become the industrial designer for the company's new electronic division led by Olivetti's son, Roberto. In this section, the exhibition becomes misleading because a small, wooden model of Olivetti's first computer, the 'Elea 3003', is shown beneath a photograph of its successor, the 'Elea 3003 Type B'. Their differences are significant. The 'Elea 3003' was a valve computer that sat on the floor with its elements linked by internal cables (and not by cables beneath the floor, as was done by IBM). The 'Elea 3003 Type B', on the other hand, was powered by transistors and its housings (as the photograph shows) were raised off the floor to reduce the computer's apparent bulk. And the modular design of its housing was inspired by the Japanese tatami mat. Few but the Japanese recognised this. It was an early example of the brilliance of Sottsass's lateral thinking.

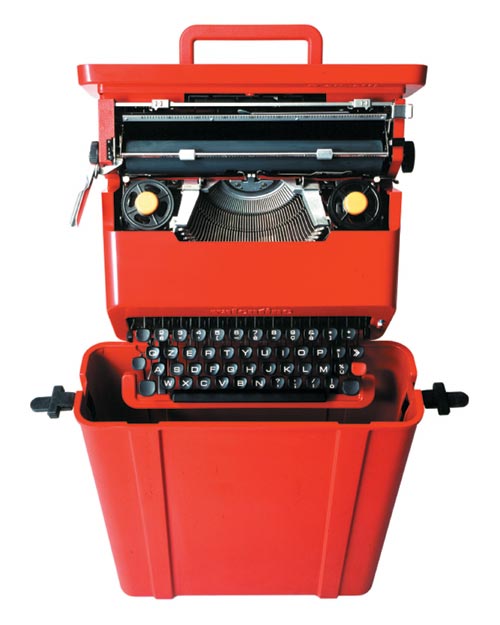

Also in the section devoted to Olivetti are Sottsass's typewriters, including the playful electric 'Praxis 48' in which Sottsass managed to get the carriage within the overall rectangle of the housing, and the manual red 'Valentine', designed with Perry A King and launched in 1979.

What the exhibition does not tell the visitor is that, originally, Sottsass had wanted the 'Valentine' to be an upper case only machine costing £10, so as revolutionary in typewriters as the biro was to the fountain pen. But the price of oil (and of plastics) rose fourfold in the early 1970s and, in the end, the most revolutionary aspect of the £30 'Valentine' was its colour.

Nor is the significance of the 'Systema 45' office furniture properly explained because it arose out of Sottsass's design of a teleprinter (the 'Te300'; 1968) whose versatility led to the idea of a system of office furniture that could be combined with all of Olivetti's electronic office equipment and would have removable panels in a range of colours that could be changed overnight - hence completely reinvigorating the office environment. This last was another revolutionary idea that was abandoned.

The exhibition then moves on to Sottsass's 'Superboxes' (1966), big wardrobes made in plastic laminates with strong, geometrical decorations that were inspired by Sottsass's meetings with members of the American Beat generation earlier in the decade. The 'Superboxes' were intended to replace furniture that tells you how to live: wardrobes have to be put against a wall and are, in a sense, two-dimensional, cocktail cabinets have to be filled with drink and deep freezers with frozen foods that are often forgotten and never eaten. The Beat generation was looking for a simpler life and the 'Superboxes' were intended to meet this need.

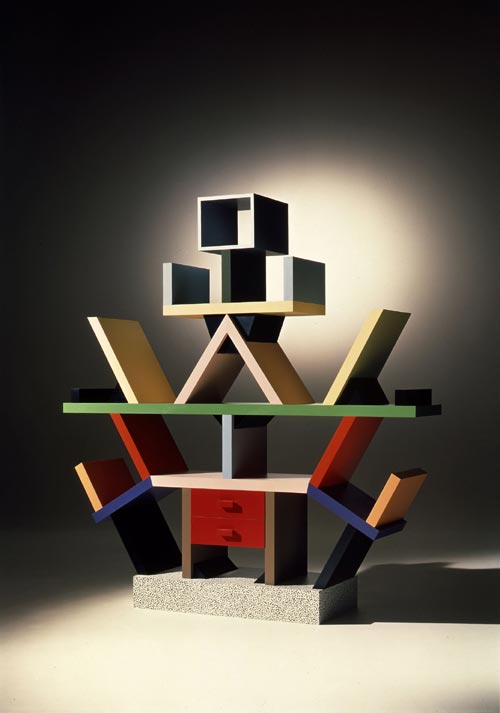

In 1979, after the break-up of his marriage and his affair with a young Spaniard called Eulalia Grau (see Sottsass's photographic record of this period, Design Metaphors), Sottsass briefly joined the Milan design group, Alchimia, before becoming a founder of Memphis, represented in the exhibition by furniture such as the Carlton sideboard and by some beautiful pieces of glass, including 'Aristea' and 'Arianna' (1986). The Memphis furniture, with its fractured, geometrical shapes, bold colours and mixing of plastic laminates with much more expensive materials, is clearly a forerunner of furniture like the 'Mobile giallo' from the Bharata Collection which was made in India in 1988 and the chest of drawers 'No 9' (1996). The latter, along with other pieces shown in the exhibition including 'Lemon Sherbet' (1986), appear to be made for specific collectors such as the Gallery Mourmans in Belgium, which is curious because Sottsass left Alchimia because it was treating furniture as works of art. But then, Sottsass has not always been consistent. In 1970, he told me that he hesitated to use new materials before they had acquired their own history, while he was using fibreglass for the 'Grey' furniture, which is also in the exhibition.

The fractured nature of Sottsass's more recent furniture is reflected in the photographs of the interiors Sottsass Associati designed for the clothes retailer, Esprit, in Germany and Switzerland from 1985-1986, while the monumentality Sottsass sought to achieve in some of his early designs derived from his experiences fighting in Montenegro during the Second World War, re-appears in the table seen in one of the room sets at the end of the exhibition. Here, too, are designs that ordinary mortals can afford: the Totem juicer, kettle and egg boiler designed by Sottsass and Mario Susani for Bodum in 1988, the Trono plastic chair designed with Christopher Redfern last year and the cutlery designed for Serafino in 2006-2007. The last mentioned looks ergonomically very suspect (as is some of the cutlery Sottsass has designed for Alessi) and could usefully be compared to cutlery by Achille Castiglioni, which is also on show in the Design Museum’s adjoining exhibition, 'Celebrating 25 Years of Design'.

Today, Sottsass has returned to his role as an architect, which he abandoned in Italy in the 1950s because the builder - not the architect - controlled how a design was implemented, and some of the houses Sottsass has designed, often with Johanna Grawunder, in Italy, America, Belgium and elsewhere reflect the geometrical simplicity and use of strong colours seen in his unbuilt Seaside Villa of 1961. And, while his 'collectors' pieces' now seem to betray the egalitarian nature of much of his early furniture (while remaining true to his belief in the sensorial nature of design), the very sensitive approach to design that is at the core of his being can be experienced by travelling through Malpensa Airport near Milan, whose interior was designed by Sottsass Associati from 1994-8. Sottsass's aim was to 'design a large, opaque interior space' that avoided shiny materials like steel, chrome, plate glass or marble to reduce glare and reflection and make the interior as gentle on the eyes as possible.

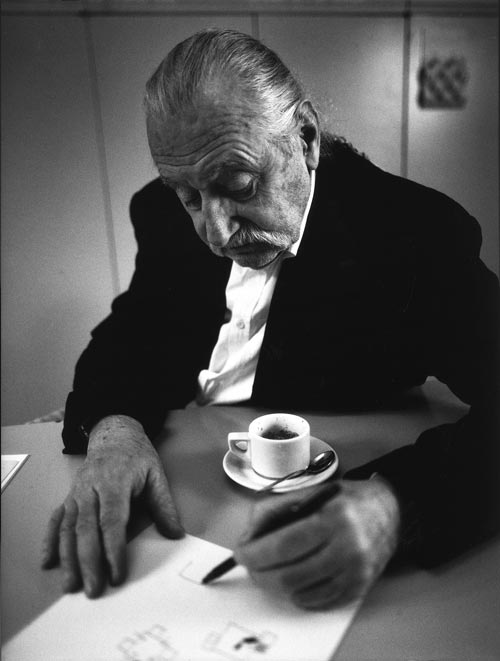

Next September, Sottsass will be 90, an amazing age considering that, in 1961, returning from a trip to India, Nepal and Burma, he became so ill that Olivetti put him into a hospital where he was expected to die. And he is still designing. But, as he said to me in 1999, 'I am a designer and I want to design things. What else can I do - go fishing?'

The exhibition continues until 10 June.

Richard Carr