Serpentine Gallery, London

23 March – 19 May 2019

by MATTHEW RUDMAN

Gallery bookshop shelves are groaning with stacks of works evangelising about art’s healing powers: how it “saved my life”, how it is an aid to mindfulness, how it is “my religion”. Seeing art as a route to a more enlightened state of being is hardly original, but it is enjoying a new cultural moment. This backdrop makes the Serpentine Gallery’s exhibition of drawings by Swiss healer Emma Kunz (1892-1963) feel particularly timely. Visionary Drawings, billed as an exhibition conceived with artist Christodoulos Panayiotou, features a selection of more than 40 abstract drawings drawn from the nearly 400 works Kunz produced during her lifetime.

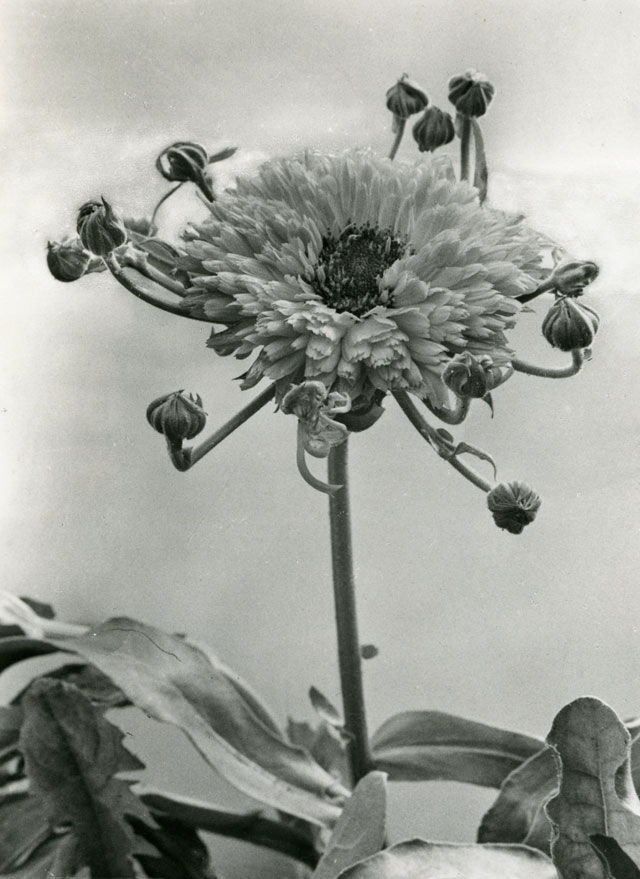

[image2]

How Kunz saw herself and how we encounter her at the Serpentine are very different indeed. Kunz described herself above all as a researcher, and was seen by her peers as a spiritual healer, able to cure diseases with the swing of a pendulum or through mysterious minerals from nearby quarries. Despite producing hundreds of drawings, Kunz’s work was never displayed publicly during her lifetime and has only recently received widespread attention.

She lived and worked in rural Switzerland, and did not train at an artistic institution. She became interested in occult healing practice in her late teens, when her father and two of her siblings died in the same year. Following this trauma, Kunz took an interest in a wide range of spiritual practices, including healing, telepathy and divination using a pendulum, known as radiesthesia. Kunz regarded her drawings as an essential part of her research-led practice, a method of understanding the universe on both micro and macro scales, and she frequently used the drawings in her healing practices with clients.

[image3]

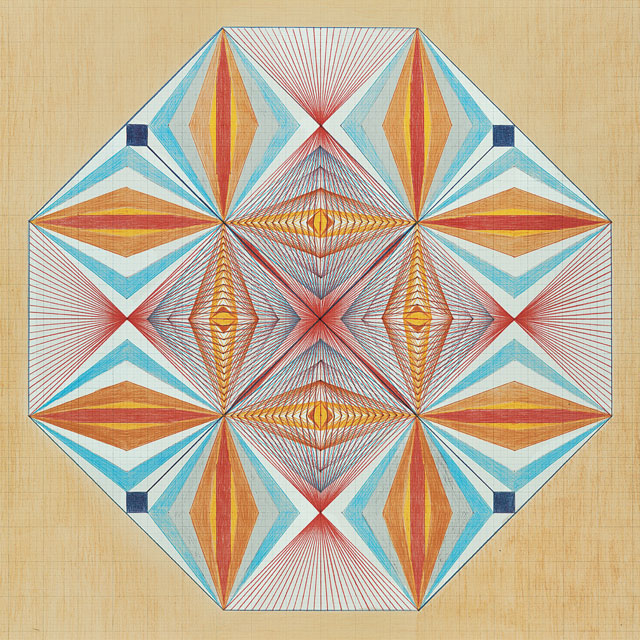

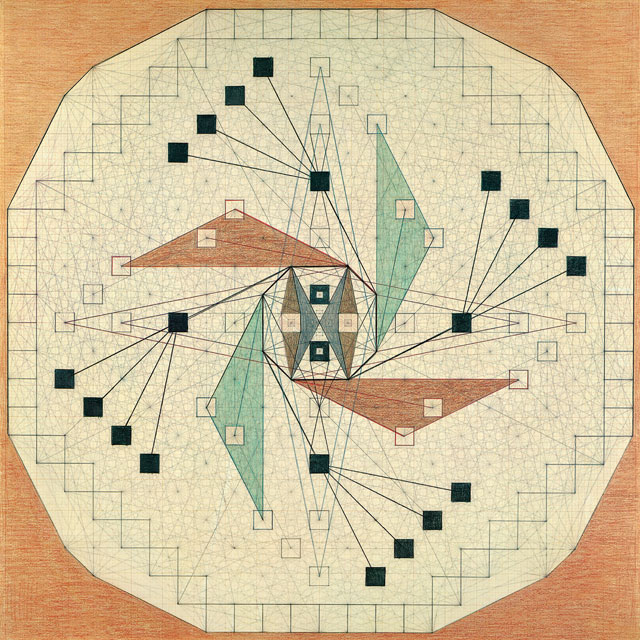

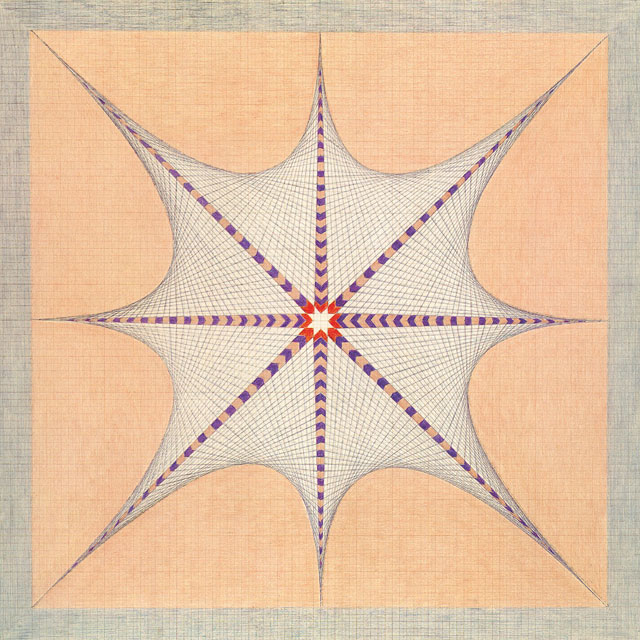

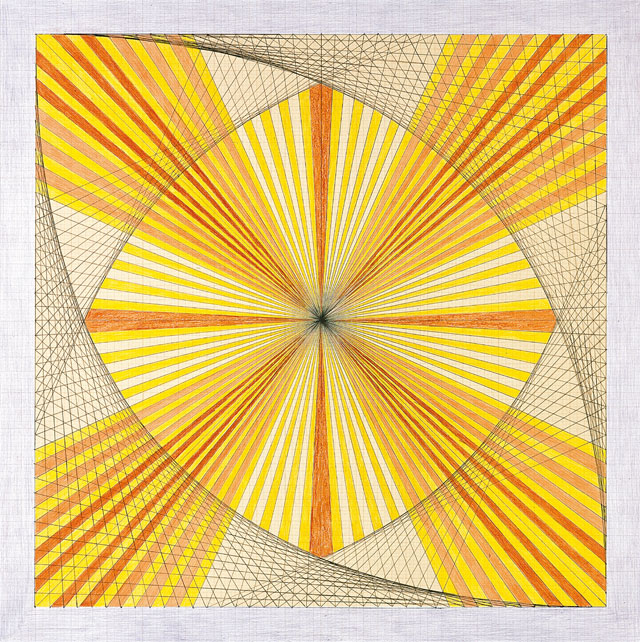

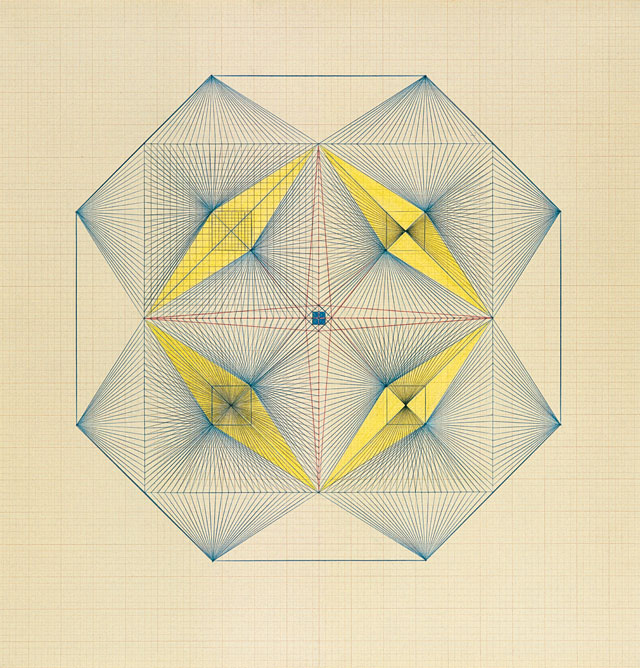

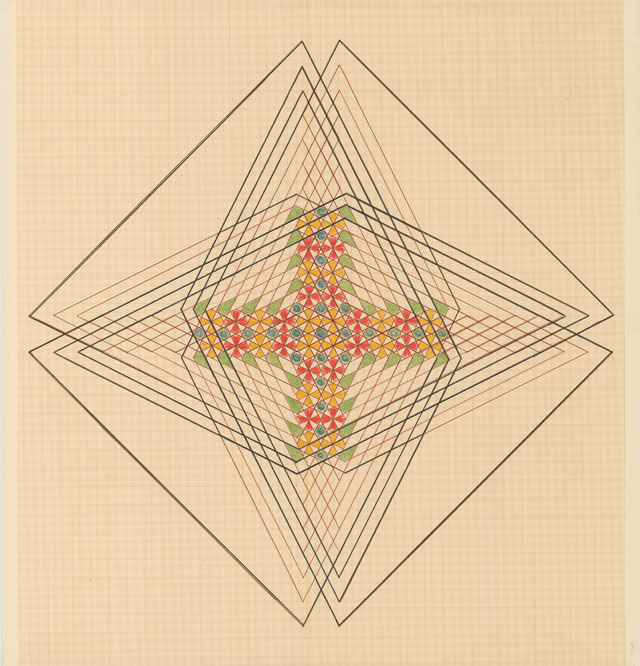

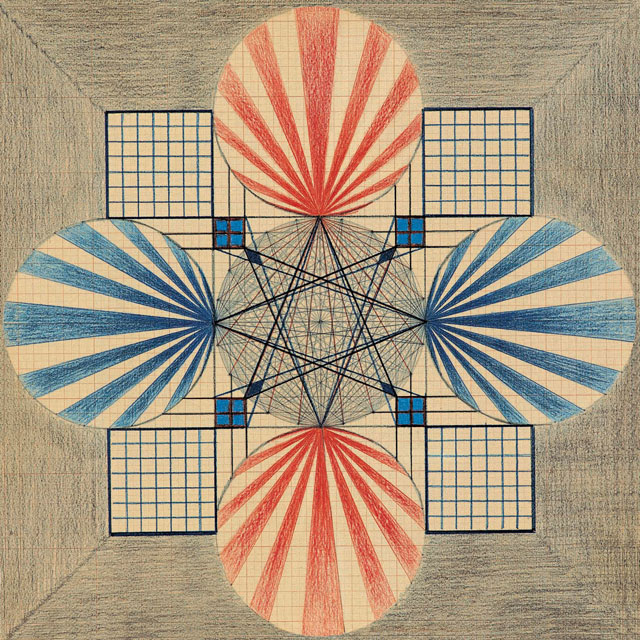

Kunz did not name or date her works, and each is produced with the same materials of coloured crayons and pencils on graph paper with blue lines. It is striking that with these basic inputs Kunz was able to produce images of such variety in shape and colour. Some drawings are pictures of totemic power, bold diamonds and pyramids, unfurling with rich tapestries of intersecting lines. Others are subtle and delicate, gradual shifts in the density of lines creating smooth colour gradients and ambiguous asymmetries.

On first view, many drawings reveal patterns you feel as if you have seen before, the work of a bored maths student perhaps, armed with pencils, a pair of compasses and too much time on her hands. But this apparent simplicity is deceptive: these works are hard to pin down, transforming depending on whether you are viewing them at a distance or up close. Stand back and you can appreciate the broad curves and latticework constructs, many of which are oddly reminiscent of early computer-generated imagery in the 1980s. Step forward and new layers appear, faint galaxies of geometric forms housed within larger polygonal superstructures.

[image4]

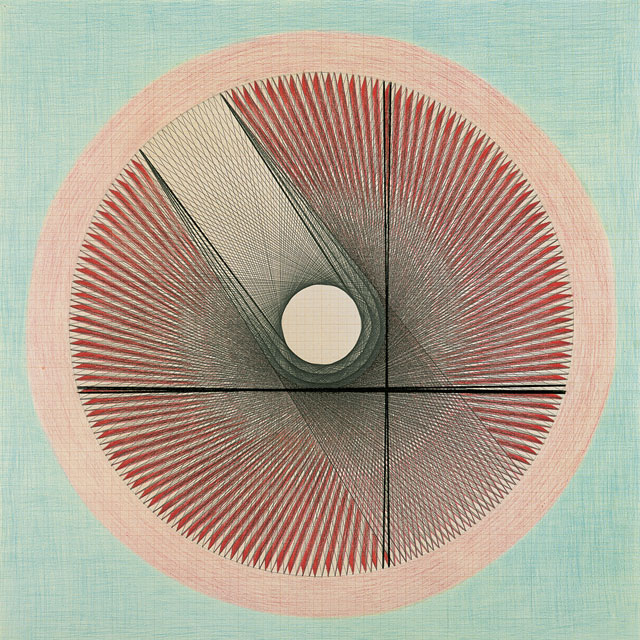

This complexity is all the more intriguing for the fact that many of Kunz’s works were produced using radiesthesia. Starting in 1938, Kunz would hold the pendulum in her hand above the graph paper and ask it questions on a variety of topics, personal, political or spiritual. She would then record the arc of the pendulum across the paper and use those waypoints to guide the structure of the eventual image.

One such drawing, Work No 020, shows a blank sphere shooting across a complex circular array of lines, resembling a comet shooting across the sun or a bullet piercing an apple. Viewing her completed work in 1939, Kunz predicted that the US was developing a new weapon capable of bringing about the end of the world.

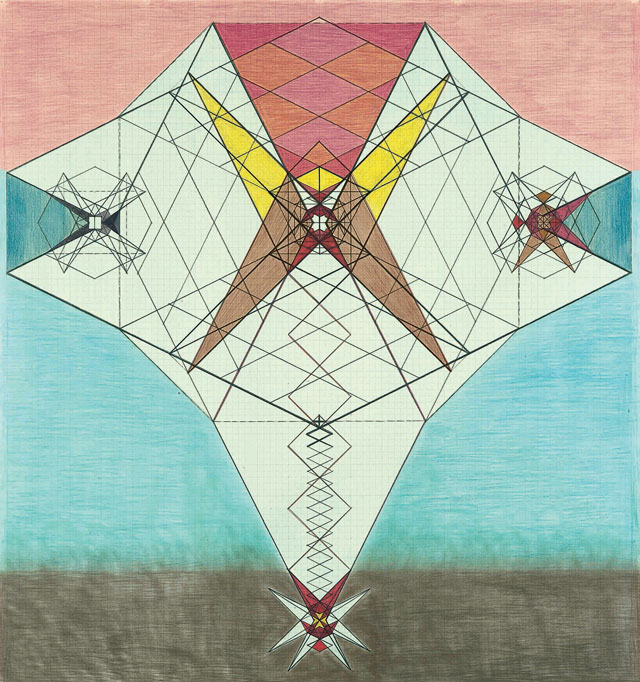

[image7]

Other works aspire to even more expansive meanings: Work No 086, also known as The Human Couple in the Cosmos, features rare figurative detail: a male and female figure formed out of simple polygonal shapes, enshrined within a sprawling cathedral of red and blue lines and branching points. The kaleidoscopic patterns of circles, triangles and spidery planes folding in on themselves invite speculative interpretation easily – is it a celebration, or a warning, a statement of subjugation or dominion over the universe? These ruminations are helped along by the general gallery ambience: low lighting, to help preserve the drawings, lends the gallery the atmosphere of a church or temple. Light flows in through skylights, illuminating the drawings arranged in a dramatic pyramid orientation on the main gallery wall, and spotlighting the stone benches made by Panayiotou for this exhibition.

The stone in these benches has its own intriguing backstory: in the early 1940s, Kunz discovered an old Roman quarry, in which she found a mineral that she named AION A, which she said had healing properties and demonstrated this by appearing to cure a local boy of polio. The exhibition benches are produced from this same mineral, which is now widely available in Swiss pharmacies as a natural remedy for muscle inflammation. It is an elegant accompaniment to the drawings, which were themselves also used by Kunz as tools for her healing practice as well as the products of her metaphysical researches.

[image8]

Kunz’s life and work has clear parallels with those of Hilma af Klint and Georgiana Houghton, both spiritual “outsider artists” who, like Kunz, used their art as a channel through which to express themselves as mediums for wider spiritual truths. The three artists were recently brought together by the exhibition World Receivers, at Munich’s Lenbachhaus, which rightly highlights the extraordinary work these three artists were creating, at the same time or in some cases years before the more widely celebrated abstract pioneers Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian or Kazimir Malevich came on the scene.

We are living through a moment of renewed interest in the supernatural, the occult and alternative approaches to understanding that are not based on rationality. In popular culture, there has been an explosion of interest in the zodiac, tarot and the practice of witchcraft, particularly in the context of female empowerment. Against this backdrop, it is unfortunate that there is not more information available to gallery-goers on how Kunz’s drawings connected to her wider practice. Visitors might be forgiven for seeing Kunz as an artist specialising in pencil drawing, rather than a multidisciplinary spiritualist and healer.

Kunz rarely wrote anything down, which does present an added challenge to illustrating the broader context to her artistic output, but viewing the drawings in a gallery setting while knowing the circumstances of their original purpose does introduce an odd dissonance. Regardless, these drawings have much to tell us: visitors will encounter whole worlds awaiting interpretation. This is an exhibition of 40 abstract pencil drawings on graph paper. That it feels so interactive, so arresting and so unexpected is an achievement in itself, and a testament to the strange and enchanting mythologies that Kunz used her work to tap into.