by NICOLA HOMER

Emma Critchley is an artist who works underwater. Born in 1980, she studied at the University of Brighton and the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. Her sustained exploration of the human relationship with this space forms the bedrock of her working practice as an artist. This encompasses photography, film, sound and installation. During her time at university, she did a marine conservation project in Indonesia, which cultivated her interest in underwater photography. On her master’s degree at the RCA, she became fascinated with free diving and the practice of holding your breath in an underwater world.

[image6]

Critchley has since built up a stellar CV, with her participation in international group shows, from Australia to Singapore, and her contributions to UK-based exhibitions, such as At the Violet Hour, held in 2018, at the Nayland Rock Hotel in Margate, Kent. She takes a deep dive into the topic of sea mining for rare earth minerals in her film Common Heritage (2019), funded by the Jerwood Charitable Foundation. The process of collaboration is often at the heart of her practice, as seen in her installation project with Lee Berwick, The Space Below, in spring 2020, which involved working with a global network of scientists to explore the issue of acoustic pollution.

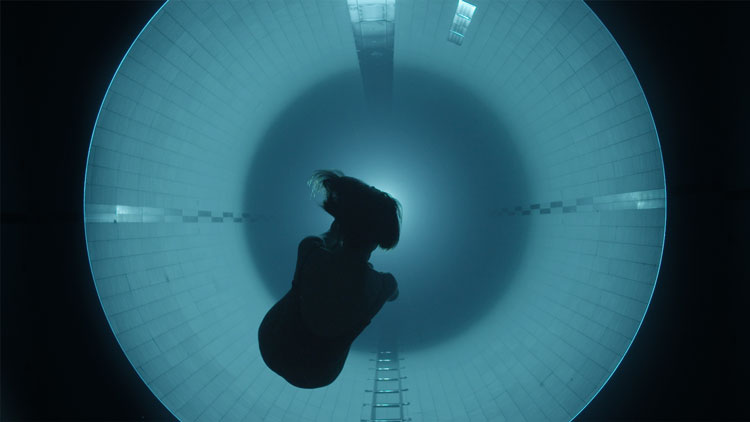

The artist is the first winner of the three-year Earth Water Sky residency programme, hosted by the Science Gallery Venice. Recently, she spent time with scientists at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, who, as part of the international Ice Memory Project, are building an archive of ice cores from melting glaciers for a future generation of scientists. One strand of Critchley’s work involved collaborating with two dancers and a free diver, and filming at the world’s deepest swimming pool, called Y-40, in Padua, Italy. Critchley is looking forward to showing the outcome of her residency, a multiscreen film installation, at an exhibition scheduled for next May, to coincide with the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021.

Studio International spoke by phone to Critchley at her home in Brighton. The following is an edited extract from that interview:

Nicola Homer: I have read that you are an artist working with photography, film, sound and installation, to explore the human relationship with the underwater environment as a philosophical, environmental and political space. I understand that you have studied at the Royal College of Art and you have also made BBC programmes, for example Radio 4’s Pursuit of Beauty: Art Beneath the Waves, looking at artists who use the ocean as a canvas. How did you arrive at the topic of underwater art in your practice? Can you talk about a specific jumping-off place?

Emma Critchley: Before beginning my art studies, I had learned to dive. I then spent a summer during my photography degree taking part in a marine conservation project, because I wanted to get back in the water again. I took a very basic, point-and-shoot film underwater camera, and that was where it came together for me. I was on a little island in Indonesia, so couldn’t get the film developed and see the pictures I was making, but it was very much the process and the experience of being in that space, being underwater where everything completely shifts, that interested me. It’s a space that we’re not used to being in, that takes us out of the everyday, so we have to realign ourselves with our sense of being. I was also looking very basically at how everything changes: light, sound, touch and smell. It was very much from an experiential position, really. The idea of using the underwater environment as a place to make work was something I developed from there.

[image7]

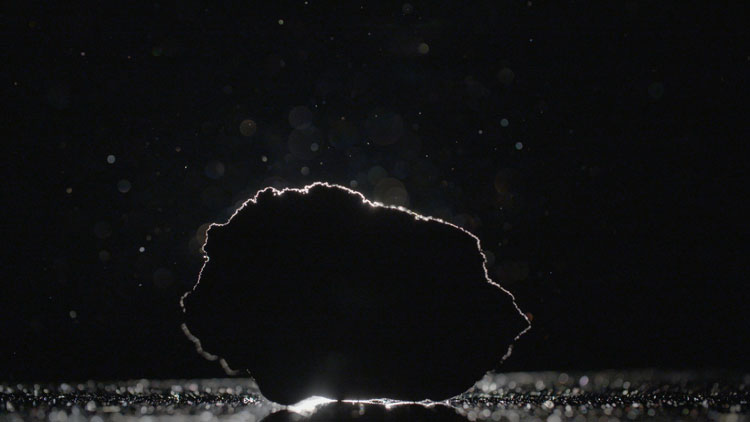

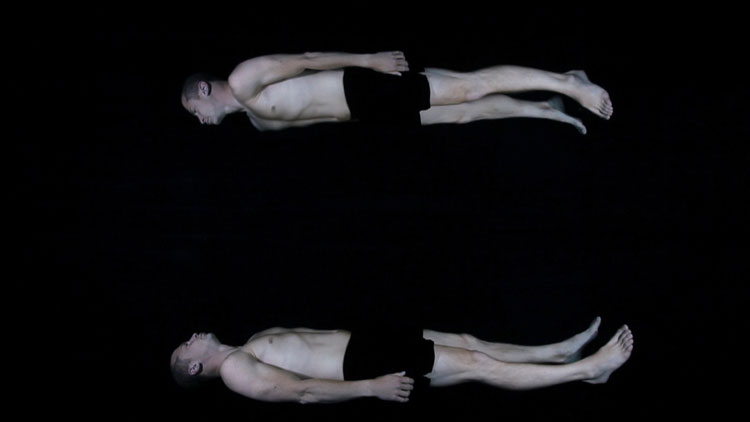

I then went on to work with free divers during my MA, exploring the breath, and thinking about the breath being what we take from the world that we inhabit every day into the underwater environment, thinking about the duration of the breath as what dictates our existence in the space. It’s about really engaging mind with body and being very aware of the immediate environment that you are inhabiting. Due to the density of water, you’re very aware of yourself being held within that space. When we’re out of water, we’re inhabiting air and atmosphere all of the time, but we don’t think about that as much. But when we’re in the water, the presence of the space that we’re in comes to the fore a lot more. That is something I became really interested in.

[image10]

NH: That’s fascinating. Now, I would like to talk about your practice in recent years, beginning with your installation for At the Violet Hour at the Nayland Rock hotel in Margate, Kent, in 2018, where artists were asked to respond to TS Eliot’s 1922 masterpiece The Wasteland. I have read that Eliot wrote parts of the poem in London at the height of the Spanish flu pandemic, a little over a century ago. In your work, how did you explore themes of The Wasteland? Can I ask you to consider this in relation to global crises today?

EC: Yes, that’s interesting. From reading the poem, the section that I became interested in was A Game of Chess, because of the dislocated sense of time, and generally, throughout The Wasteland, there is this sense of critical exhaustion. These are the two themes that I became most interested in. I was thinking about them in relation to the psychology of how we are handling the environmental situation. At the moment, it feels like there is a distorted relationship between future and present, in the sense that climate catastrophes are playing out around us all the time, but in some way, it ’s still being conceived as a future crisis rather than a present-day crisis. We’ve got mass flooding and forest fires on a global scale. In Europe, Venice had its biggest Acqua Alta this year for example, but we’re still not fully engaging with the crisis and want to carry on with everyday life as it is, because it is comfortable.

[image11]

With the installation, there was a room in the hotel, on the third floor, where the sea had started to come in through cracks in the walls and windows, and some of the wallpaper had started peeling away. I worked with this to create a room that appears to flood at high tide and a character who lives an existence with this flooding: they are continuing life as normal, but have adjusted the room, so all the furniture is above the high-tide line.

I’m interested in the lack of willingness to fully engage and change the way we go about our lives. That’s why I was interested in the installation being set within this familiar space that the viewer can inhabit. We have been at a critical stage for years, but it doesn’t feel as if it’s met with the same level of urgency in our everyday lives.

[image2]

NH: That’s very prescient when we think about the climate crisis today. You give a good example of the flood in Venice that occurred recently, as I know that you have been spending a bit of time there. Now, I understand that in 2019, you released a film called Common Heritage, funded by the Jerwood Charitable Foundation. The premise appears to be the drive to explore the sea floor and the imminent gold rush of deep-sea mining for rare earth minerals. The film reveals how industrialisation has affected the human relationship to the environment. One element is a science fiction writer’s narration of a speech from 1967, by the Maltese ambassador to the United Nations, which introduced the Common Heritage of Mankind principle. Can I ask you to tell me about why you selected this speech as the provocation for the film?

EC: Yes. When I first read the speech, what interested me is how positive and hopeful it was. The speech was written off the back of two world wars, and Arvid Pardo talked about how the discovery of the riches of the deep could be a moment in time that could break us, or it could make us, as a world, as united nations; how potentially they could be shared among the wealth of nations and wipe out poverty, and we could all start equally. Pardo goes into immense detail describing the extent of the discovery. There are moments in the speech where the language is very evocative, and to me it felt like a science fiction narrative in the way he paints pictures of possible futures, but he also warns of possible grave implications. In the film, I wanted to play off these future scenarios with the reality of the way history has unfolded. The speech led to more than a decade of United Nations conferences on the Law of the Sea in order for the world to agree on guidelines for how the high seas should be managed, which just shows the extent of the task. The speech is still pertinent today, as the initial exploration licences have started running out and exploitation licences are imminent.

[image3]

NH: Yes. It’s interesting to consider the speech in relation to the wider context of the birth of the environmental movement that was happening around that time. I’m wondering if you have any thoughts on how this speech might highlight themes of environmentalism that were coming to the surface in the 1960s?

EC: What’s quite interesting about the speech, considering the time it was written, is that it doesn’t question whether we should leave the riches where they are; it feels like it’s a given that they will be mined. As you hear in the film, there are, of course, huge environmental concerns expressed about mining the deep ocean, but to me it feels the main focus of the speech itself is thinking about where the minerals are, and who has the right to mine them, to own them, to benefit from them, which is more aligned with some of the social justice concerns of the environmental movement.

[image4]

NH: I would like to move forward now to your latest work in 2020. I understand that you have just completed a collaborative project with Lee Berwick called The Space Below, in London. I gather this was an immersive sound installation, designed for a subterranean location, where you explored the issue of acoustic pollution, and this has spread to many corners of the world, from shipping lanes in the English Channel to the silent waters of the Arctic. I also understand that this work featured in a BBC programme that you made about artists working with pollution. Could you tell me a bit more about your sound installation and how it facilitates the understanding of environmental issues today?

EC: The Space Below was a multi-speaker sound installation in the Greenwich Foot Tunnel, which runs under the Thames in London. The idea was to bring awareness to the issue: underwater sound pollution is one of the huge problems of the ocean. The idea with the installation is to immerse visitors in a sonic world and think about how underwater, sound is the primary sense for all creatures that inhabit that space. This space is traversed by many people every single day. Visually, everything looks the same, but, sonically, the space is transformed through sound. Sound pollution has a chronic impact on everything from whales that use sound to navigate their way through the oceans to tiny larvae that listen to the sound of coral reefs as a way of navigating and finding where to settle. It’s affecting all creatures in the ocean. We’re a very ocular-centric species as humans, but for the creatures that inhabit that space, sound is their primary sense.

It is an installation that people walk through. At either end, there is this immersion into the amazing sonic space that the creatures inhabit, which is then infiltrated by human-made noise. We have these incredible sounds of walrus bells and narwhal calls that sound completely otherworldly. We are looking at the relationship between the human sounds and the natural sounds, so, not only do you get the sense of this incredible sonic world, but also the impact that our sounds are having. It’s experiential, rather than wanting to specifically say these sounds are affecting these species.

NH: I can see that this installation provided for an immersive experience that might have helped visitors to reflect on the issue of acoustic pollution.

EC: Yes. The sounds were collected from scientists around the world, who are studying underwater sound pollution, or sound recordists interested in the subject. We have built a website (thespacebelow.org), so people can access the sounds and the research behind the sounds that were recorded.

Through the research, we have been able to connect with a community of people across the world who are actively engaged with the issue. We worked with Jennifer Jackson and Iain Staniland at the British Antarctic Survey. Jennifer’s main interest is whales and whale calls, and how they differ according to different groups; she connected us with whale specialists working with specific groups of whales, such as Chilean whale calls, as opposed to whales from the Atlantic coast. One key scientist is Kate Stafford from the University of Washington, who has done a lot of work in the Arctic and a TED talk on sound pollution. Another key scientist from the project is Brandon Southall from the California Ocean Alliance.

This project was about collaboration and building a community. We would like to grow the research base and tour the installation to different subterranean locations where this issue is pertinent. We were lucky to have great partners for the installation: it was funded by the Arts Council, the British Antarctic Survey and the Royal Borough of Greenwich. Minirig and The National Maritime Museum were also partners, so the launch started at the museum and we did all the tours from there. The last day of the installation was just before the lockdown began in March. The only thing that didn’t happen was the public talk at the National Maritime Museum.

[image8]

NH: Now, I would like to ask you to talk about your Earth Water Sky Residency, hosted by the Science Gallery Venice. I understand that you have been developing work to show at an exhibition that will be held at the same time as the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021. It sounds interesting as it involves a collaboration between artistic and scientific communities. I’m wondering if you could tell me a little bit about the project, and how this collaboration between artists and scientists works in this instance?

EC: Yes. My residency happened last year. The Earth Water Sky Residency runs for three separate years with three different artists each year. The artist is connected with a different project each year. I was working with the Ice Memory project, which is a global project and the lead scientists are in Grenoble University in France and Ca’ Foscari University in Italy. I was working with Professor Carlo Barbante at Ca’ Foscari University. It’s a beautiful idea, in the sense that they are collecting ice cores to create an archive in Antarctica. The cores are a record of our climatic past and this collection is for future generations to analyse. They do take cores from polar regions, but there is a focus on non-polar regions, because the glaciers here are disappearing so fast.

When they are taken out of the ground, the scientists take three cores: one is analysed and two go down to Antarctica. What Carlo talks about is that scientists of the future, the children of the day, will be able to analyse these cores in ways that they can’t even imagine at the moment, because of how fast science is developing. So, it’s really important to have these records, so that they are able to analyse them, and use them as a way of dealing with the climate in the future.

[image9]

I spent two months in Venice, on two trips, and spent a lot of time talking with Carlo and the Ice Memory Project team and researching through conversations and looking at papers. One of the main inspirations has been in exploring the notion of interconnectivity and circulation. This began in relation to looking at global movement systems of wind, water, chemicals and particulates, which is how, for example, toxins from a mine in Chile can be found in the ice layers of a glacier in Antarctica. As it was explained to me; these are global patterns, which on a global scale appear to always move in the same way, yet when you look closely they are always different.

I became interested in how the cores can reveal inter-relationships between climatic and societal events, which has very much informed the work both in the script and development of the choreography. To give an example, a volcanic eruption in Iceland contributed to the French Revolution, due to disturbed weather patterns causing large-scale food poverty (one of the main contributors of the revolution). Or conversely, the European colonisation of the North Americas led to a significant decrease in C02 levels, with subsequent climatic impacts, because the extent of human life lost left swathes of agricultural land abandoned and taken over by trees.

From quite early on in the residency, I became interested in thinking about different ways of knowing and different forms of knowledge, from scientific data to everyday experience. What also stood out was the importance of acknowledging who is conducting the research, whose histories are being told and by whom. Unlike the layers in a core, history is by no means linear and a story very much depends on who is telling it and where it begins. The work has therefore become a collection of different forms of knowledge, bringing together scientific papers and historic events with interviews I did remotely with people who are encountering glacial retreat on a daily basis in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania, and the Quelccaya ice cap in Peru. This notion also informed the development and making process of the work itself, as we ran a series of workshops: firstly, a narrative workshop with one of the Ice Memory Team, Francois Burgay, using storytelling as a way of animating and inhabiting the research. In partnership with Centro per la Scena Contemporanea, we ran a series of workshops with dancers in and out of water, where elements of the research were explored through movement, which eventually contributed to the choreography in the final film.

NH: It is really interesting to hear about your interviews with people who live close to places where glaciers are melting. Can I clarify what is the plan in terms of the final output for this residency?

EC: I’m still working on it at the moment, but it will be a multiscreen film installation that weaves together these different forms of narrative that are taken from conversations, from scientific papers, from articles and from interviews, as well as my own thoughts and reflections. I worked with two dancers and a free diver and, from the research, we choreographed in-water movement, so the body is suspended in water like the air within the ice cores. This was filmed at the beginning of this year in Y-40; the deepest indoor pool in the world, which is just outside Venice. We are working towards an exhibition of the work in Venice, in May 2021.

NH: Meanwhile, how can readers find out more about this project?

EC: They can visit the Venice Science Gallery Venice website and follow my website and Instagram channel.

NH: Finally, what are your hopes and dreams for the future?

EC: I guess it’s continuing with this collaborative approach to find new and interesting ways of using art as a way of trying to engage and have conversations with as many people as possible about this climate crisis that we’re in.

• Emma Critchley will be speaking about her work and her residency in conversation with Earth Water Sky curator Ariane Koek as part of the Science Gallery Venice online programme on 30 September 2020 at 16.00 CET (15.00 GMT)

She will also be in conversation with current Earth Water Sky artist in residence Haseeb Ahmed on 14 October 2020 at 16.00 (15.00 GMT). For details on how to watch these events, check here: https://venice.sciencegallery.com/news