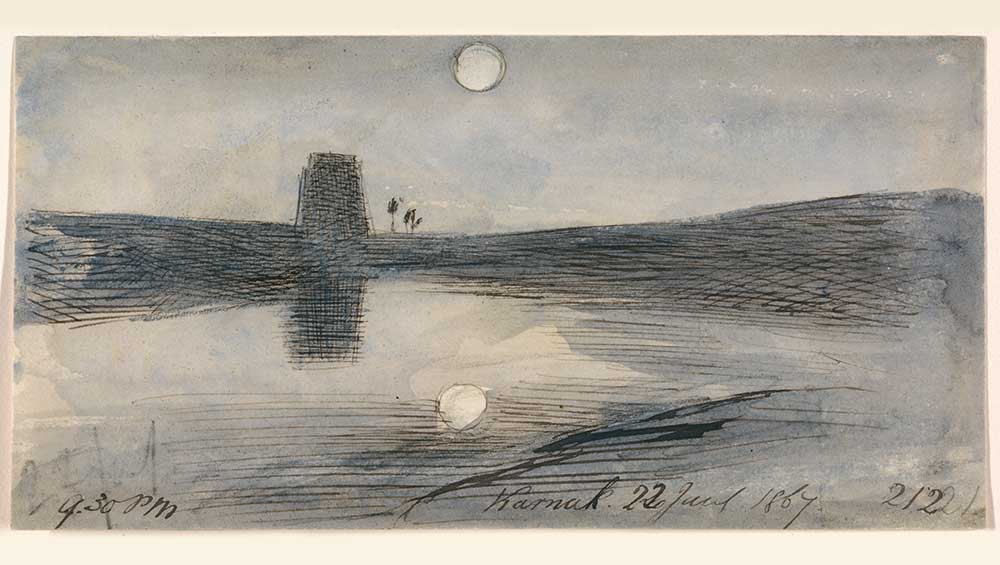

Edward Lear, Karnak, 9:30 pm, 22 January 1867 (212). Watercolour with pen and black ink over graphite, 8.7 x 17.1 cm. Courtesy Yale Centre for British Art, Gift of Donald C Gallup, Yale BA 1934, PhD 1939.

Ikon, Birmingham

9 September – 13 November 2022

by JOE LLOYD

There are many sides to Edward Lear (1812-88). The most familiar one is the nonsense poet, author of The Owl and the Pussy-Cat (1870) and the Book of Nonsense (1846), the latter an illustrated collection of limericks so popular that it went through three editions in his lifetime. But Lear did much else besides. He wrote recipes. He set Tennyson’s poetry to music. In his own mind, however, Lear was a primarily artist – and a very distinctive one. He was focused on two genres. For “bread and cheese”, he specialised in drawing animals, in particular birds (David Attenborough has called him “the finest bird artist there ever was”). In private, he produced numerous coloured landscape drawings.

Edward Lear: Moment to Moment, at Birmingham’s eclectic Ikon, is the first exhibition devoted to this latter category. It gathers 59 drawings, in ink and watercolour, from private and public collections. Many have never been exhibited before. The drawings depict wide swathes of the world. Lear was prolific, finishing around 9,000 works in his lifetime. He travelled prodigiously by the standards of his time. He went to Albania, Greece, Turkey, Egypt and India. He captured the ruins of the Sahara and the peaks of the Himalayas. Like many artistically minded English people of his era, he had a particular affinity for northern Italy, and eventually settled down in Sanremo on the Ligurian coast.

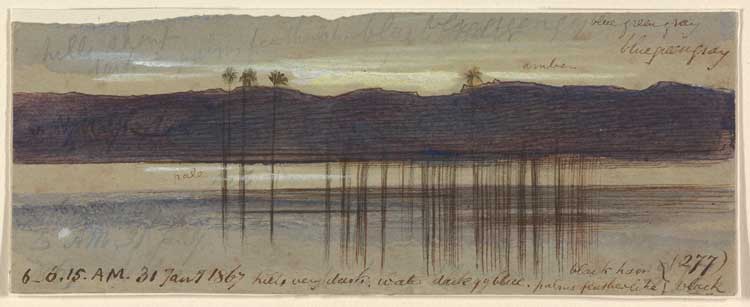

Edward Lear, Philae, 6:00-6:15 am, 31 January 1867 (277). Watercolour with pen and brown ink over graphite, 5.4 x 13.7 cm. Courtesy Yale Centre for British Art, Gift of Donald C Gallup, Yale BA 1934, PhD 1939.

Lear’s journeys were not simply the result of wanderlust. He was probably a closeted homosexual, not an ideal identity to hold in censorious Victorian England. He also suffered from perennial ill health from childhood, including asthma and epilepsy. Epilepsy was heavily stigmatised at the time, and Lear became a nomad in part to avoid the condemnation that might result. In consequence, his life was a relatively lonely one, of thwarted passion and unconsummated desire. He cultivated the manner of an antique eccentric, but he was prone to fits of “the Morbids” that left him paralysed. His closest relationship may have been with his portly tabby cat, Foss, whose death in 1887 presaged Lear’s own.

With the exception of some works produced for publications, Lear’s landscape drawings were not intended to be viewed by the public. Literary scholar Matthew Bevis, who curated the exhibition with Jonathan Watkins, the outgoing director of the Ikon, writes: “Many of these pictures were aide-memoires, references, trials for future work. But they were also something more: a way for Lear to inhabit and question his experience, and to live in and beyond the moment.” They bear the landmarks of Lear’s relatively lonely existence too. There are very few figures, and when they appear they are barely detailed. At the bottom of one 1868 drawing of Calvi, Corsica, Lear sketches a not-quite-human figure he notes as “a dantesque female!”.

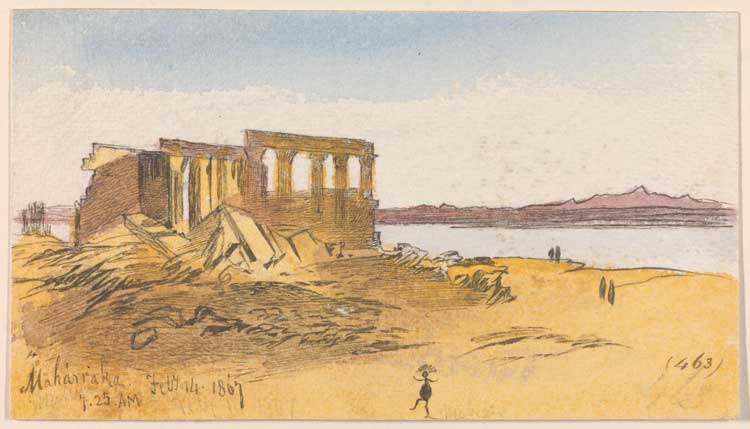

Edward Lear, Maharraka, 7:25 am, 14 February 1867 (463). Watercolour, pen and brown ink, and graphite, 9.8 × 17.5 cm. Courtesy Yale Centre for British Art, Gift of Donald C Gallup, Yale BA 1934, PhD 1939.

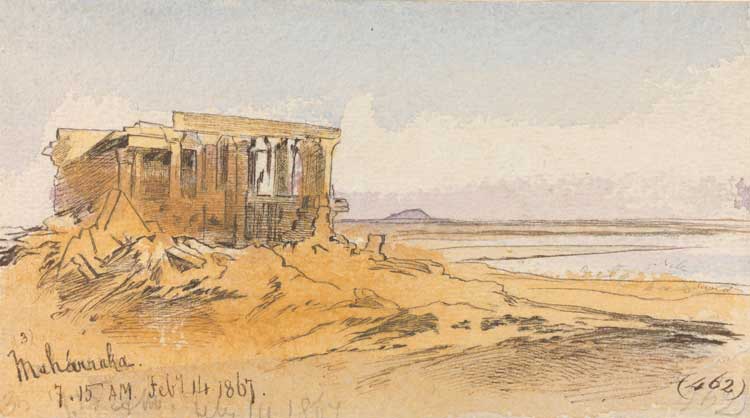

The majority of his drawings contain such notes, most often describing date, location, time of day and weather conditions. One watercolour of Ibreem (1867), the Qasr Ibrim archaeological site in Egypt, was “done under extreme difficulty – by a quarter noon outside”. Sometimes, he would draw the same subject repeatedly at different times of day: a pair of pictures of Karnak, Egypt (1867) show it at 9.30pm and 10pm, while the ruins in Maharraka, Egypt (1867) are captured at four five-minute intervals. Sometimes the marginalia become more whimsical. A view of Savona (1864), in northern Italy, is decorated with a near-verse: “O wind! / O cold! / O stones! / Oh sand!”.

Edward Lear, Maharraka, 7:15 am, 14 February 1867 (462). Watercolour, pen and brown ink, and graphite, 5.9 x 17.5 cm. Courtesy Yale Centre for British Art, Gift of Donald C Gallup, Yale BA 1934, PhD 1939.

For the most part, however, Lear’s drawings avoid the nonsense that made him famous. They are straitlaced, almost conventional. But they are also often extraordinarily beautiful and meticulously detailed. One 1866 work depicts the Port of Ragusa (today’s Dubrovnik) stretching out into the sea. Lear captures the buttresses of the Church of St Ignatius, the slits in the walls and the country houses on the hills above the city, all on a minute sheet of paper. The earliest piece in the show, from 1848, surveys Constantinople sprawling across the Bosphorus, with domes and minarets recognisable today.

These works are all the more remarkable given Lear’s technique. Once he arrived at the chosen viewpoint, he would pull out a monocular lens, spend a few minutes surveying the details, then set down his impressions with enormous speed. “He would put on paper the view before us,” said his friend Hubert Congreve, “mountain range, villas and foreground, with a rapidity and accuracy that inspired me with awestruck admiration.” The sepia ink and brush-wash were added later, during winter evenings. Here, too, there is an impressive sense of ease. The Ragusa drawing captures the way the ocean shades from reflective to matt, and the effect of the sun on its hue.

Edward Lear, The Forest of Bavella, Corsica, 7:10 am, 29 April 1868. Pen and ink and watercolour on buff paper, 63.5 x 80 cm. Private collection. Photo: Woolley and Wallis Salerooms Ltd.

Lear lacks polish. He rejected formal education, lasting just a year at the Royal Academy schools. He is seldom able to create true imitation of depth. But what might have been a deficiency instead gives his work its distinctiveness. As Bevis writes: “The more painterly or ‘finished’ he tries to be, the further away he gets from the sources of his own strength.” Lear’s spindly, sinuous lines have a palpable spontaneity, and the freeness with which he applies the wash gives his landscapes an almost otherworldly quality.

As with his hero Turner, over time, Lear seems to move further from direct representation. Three drawings entitled Forest of Bavella (1868) are washed with luminous streams of colour. A view of Ootacamund, southern India (1874), drawn over the course of an entire day, features a string of trees that grow out of the ground like stalagmites, while Kandy (1874), in what is now Sri Lanka, is suffused with a chartreuse glow. Lear is capturing not what he sees, but what he imagines he sees. He referred to his art as “poetical-topographical”. And this combination of representation and imagination lends his landscapes a particular charm.

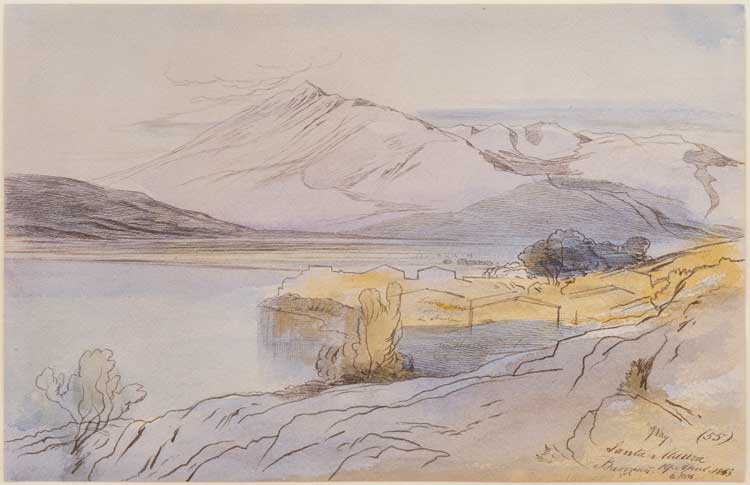

Edward Lear, Santa Maura Fortress from the West, 6:00 pm, 19th April 1863 (55). Watercolour over pen and ink, 21 x 32 cm. Private collection.