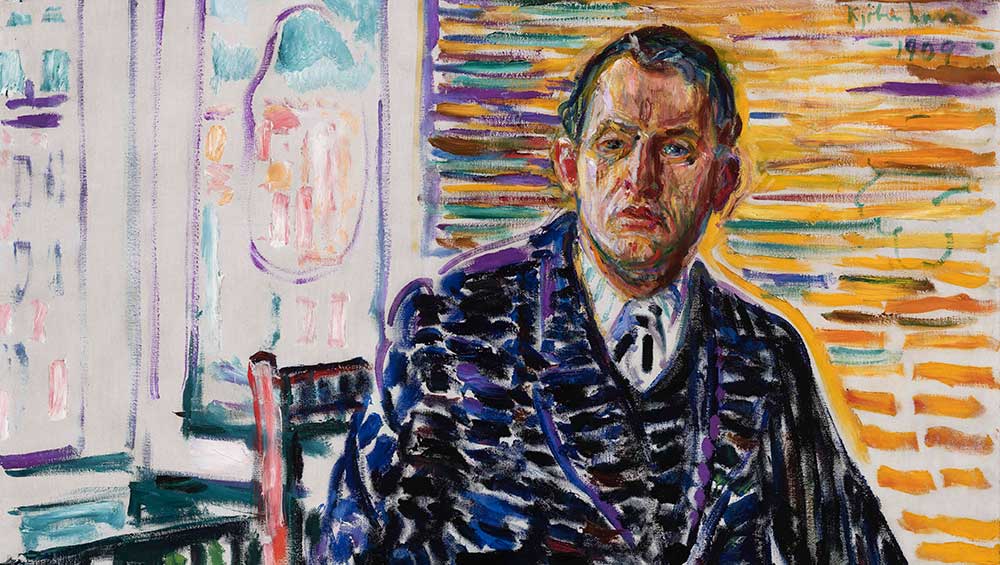

Edvard Munch. Self-Portrait in the Clinic, 1909 (detail). Oil on canvas, 100.7 x 111 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

Courtauld Gallery, London

27 May – 4 September 2022

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Morning, a painting of luminous beauty and simplicity, is a fitting introduction for this new presentation of Edvard Munch (1863-1944) at the Courtauld Gallery, with works from the collection of Rasmus Meyer (1858-1916) at Bergen’s Kode Art Museums, many seen for the first time outside Norway.

Edvard Munch. Morning, 1884. Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 103.5 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

Dated 1884, Morning depicts a young woman, clearly recently roused from sleep but sitting, almost fully dressed on the side of her bed, ready for work. Only one foot remains unclad. Her dreamy expression as she looks towards the morning sunlight through her window, and her relaxed and sleep-softened posture and features imbue the painting with a sense of intimacy and everyday poetry, not least in the tender detail with which Munch reveals her raw, work-roughened hands; the blouse with one button still unfastened evoking her not quite alert mental state. Painted when Munch was only 20, it shows his early mastery of texture, tone and light, and his early inspirations drawn from the French impressionists, whose simple, everyday scenes of ordinary folk and nature, captured in rough, rapid-fire brushstrokes represented a radical rejection of the ponderous exactitude and lofty themes of the prevailing art establishment.

Not a trace of the existential angst for which Munch has become so famous is apparent on this young woman’s face or in her demeanour. And surely it has been some time since any London art lover has associated Munch exclusively with his most famous work, The Scream (1893). There have been two excellent London exhibitions in the last three years that sought to expand our sense of who Munch was and why he remains important. The British Museum’s show of 2019 (Edvard Munch: Love and Angst) revealed a broader perspective on the interior life of this sensitive, troubled, and talented artist over several decades. At the Royal Academy, in 2021, he was paired with Tracey Emin (Tracey Emin/Edvard Munch: the Loneliness of the Soul), who claimed she has been “in love with this man” since she was 18. In that show, 18 of his watercolours and oils, drawn from the Munch archives in Oslo, showed such clear empathy for, and engagement with, his female subjects of all kinds and age, that they stood out as exemplary, compassionate counterpoints to Emin’s tendency towards morbid self-absorption. That show, in particular, made me want to get to know Munch better.

Edvard Munch. Spring Day on Karl Johan Street, 1890. Oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, Gift from Bergen Art Society, 1925.

Luckily, I was one of several UK critics and writers invited to the original Rasmus Meyer collection, from which this Courtauld show is drawn, in early 2022. The visit deepened our understanding of Munch and of Meyer, who was serious about his collecting, liking to acquire works from across an artist’s lifespan so he could study, support and share in their evolution. There were many sketches and half-finished paintings there, but in the context of dozens of brilliant, finished works, they fitted in naturally to that narrative arc. I found it particularly interesting – even brave – to show the work Spring Day on Karl Johan Street (1890), which is clearly Munch’s attempt to follow Seurat’s experiments in pointillism, albeit with a Norwegian urban landscape as subject. But it is not a particularly outstanding example of its kind. How refreshing, I thought at the time, to share that with the public: sometimes we need reminding that painters of masterpieces don’t hit the sweet spot in every work.

That work is also exhibited here. But this is where I take issue with the selection criteria for this show: there are not enough of the more brilliant or arresting of Munch’s works, despite the show’s title, to balance out those that are less finished or more experimental. Scanning the presentation of 20 works (and I swear we were told there would be 30), in my opinion, only half of them come close to, or fully warrant, the “masterpiece” rating of which the show’s title speaks. This is not to say they don’t have value within Munch’s evolutionary story, but it seems to me that this presentation doesn’t do Munch justice if it is aimed at articulating why he takes up so much space in the Norwegian art canon of the late-19th and early 20th century - almost single-handedly representing the country’s contribution to art in that period, nationally and internationally.

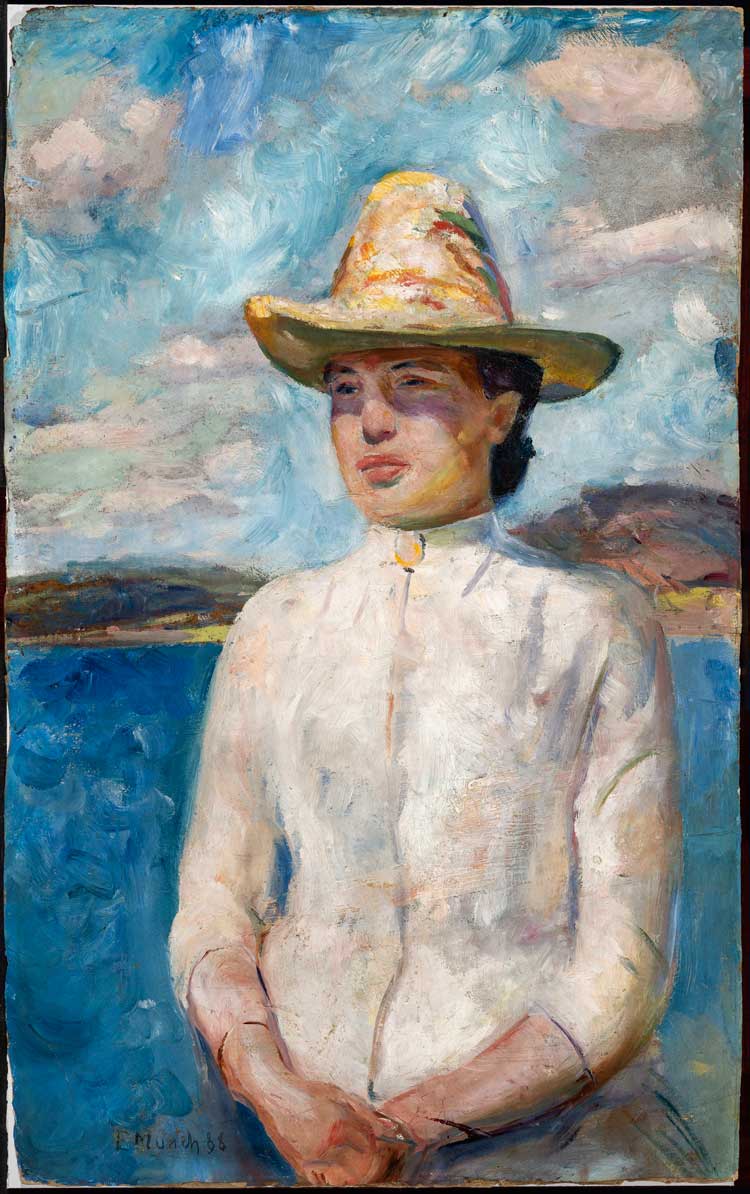

Edvard Munch. Inger in Sunshine, 1888. Oil on unprimed cardboard, 73 x 46 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

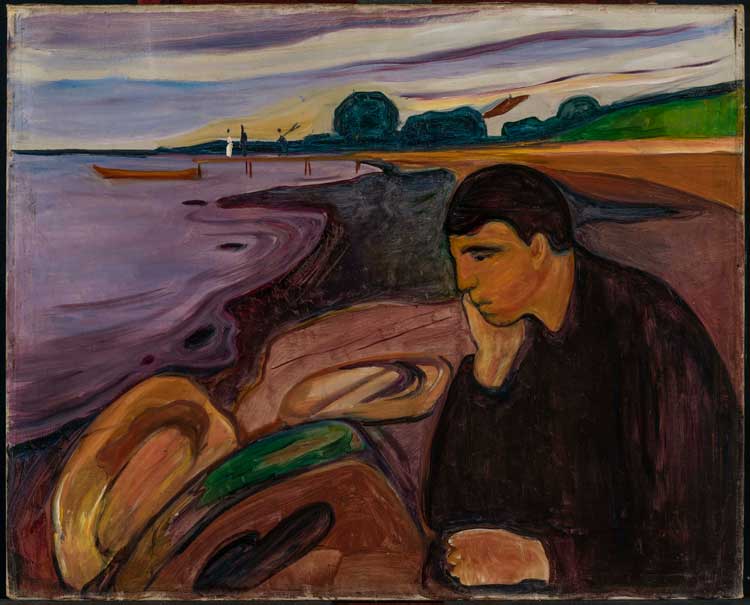

What further diminishes the presentation is the chronological inconsistency of the hang. Morning is one of his earliest works and the one that established him as a talent to watch. Next to it is Inger in Sunshine (1888), but, despite being painted four years later, it isn’t as good. The subject is his sister, whose figure positively radiates light, but it is rather let down by an overworked and clunky sky. We then jump a decade from Morning to Melancholy (1894-96), a painting that marks a shift into his more depressive period.

Edvard Munch. Melancholy, 1894-96. Oil on canvas, 80 x 100.5 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

Just two paintings later, we skip back five years to the remarkable and luminous Summer Night: Inger on the Beach (1889). A caption, helpfully, tells us: “The painting is often considered to be the moment Munch found his unique artist’s voice … (combining) the fusion between the figure’s emotional state and her surroundings, as well as the technique of distilling essential shapes and colours.” Surely this painting should have preceded Melancholy, if the attempt is to show Munch’s evolution, both expressively and emotionally. That kind of inconsistency niggles.

Edvard Munch. Summer Night. Inger on the Beach, 1889. Oil on canvas, 126.4 x 161.7 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

The second of the two small galleries in which the show is sited announces its theme as “From ‘the Frieze of Life’ to the New Century”. I find it puzzling that the first painting in this room – if we follow the natural inclination to go to the right of a doorway, immediately following the major wall text – zooms us along to 1909 with a bold but seemingly unfinished portrait of Munch, Self-Portrait in the Clinic, a painting made during his recovery from a nervous breakdown, and one that “heralds the beginning of a new era for the artist”, according to the caption. You would expect a statement like that to be followed by several of these subsequent “new era” works, but none of the paintings that follows is from later than 1909 – in fact, most of the works in this room predate 1909, with many hopping back into the 19th century.

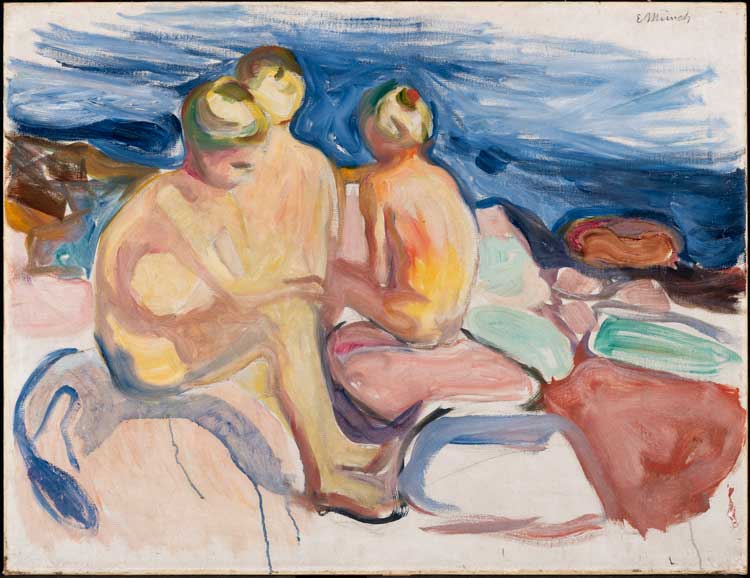

Edvard Munch. Bathing Boys, 1904-05. Oil on canvas, 70.1 x 91.3 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

Immediately next to the self-portrait is a work that feels semi-completed, a grouping of young male bathers at the seaside, Bathing Boys (1904-05), followed by a striking, full-length nude male, whose form exudes confidence and vitality, Youth (1908), though the roughness of the background implies that it, too, is unfinished. There is a charming painting called Children Playing on the Streets of Asgardstrand (1901-03) and then one of the many paintings he made for his Frieze of Life series, hoping to depict all the major life stages from birth through illness to death, called Four Stages of Life (1902).

Edvard Munch. Evening on Karl Johan Street, 1892. Oil on canvas, 84.5 x 121.7 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

The four women he depicts paint a far from cheerful prognosis: from the bright-eyed, cheerful face of the young girl, it is all downhill, judging by the careworn expression of the young woman to one side of her, then the cadaverous visage of the middle-aged woman and the crouching, hunch-backed elderly woman behind. It is no surprise that, with its sombre and subdued street scene, this is a work from his gloomy late 1890s/early 1900s period. But then we ping back in time to Evening on Karl Johan Street (1892) and a foretaste of The Scream, with the skull-like, hollow-eyed faces of a crowd of theatregoers on a winter’s night. Beside this is a scene taken from the deathbed of his beloved sister Sophie, who died from tuberculosis at the age of 15 – a disease to which he also lost his mother … no wonder the man had a melancholy bent. At the Deathbed (1895) places us at the emotional centre of that loss, thanks to the powerful combination of mauve, grey and black, and the drained visages of the grieving figures.

Edvard Munch. At the Deathbed, 1895. Oil and tempura on unprimed canvas, 90.2 x 123.3 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

It is said that Munch had a difficult relationship with women, but his love for this lost sister (and mother) as well as his sister Inger is clearly expressed. Some critics have gone further, to complain of the negative portrayal of women in this show. Perhaps he was reflecting no more than the grim reality of their lives within the dour, patriarchal and Lutheran culture of late-19th-century Norway. Two nearby paintings, which are also studies for his Frieze of Life, show a red-headed female figure: it may be the same woman in each, it’s not clear. Either way, she is a glorious subject, especially as seen in Nude in Profile Towards the Right (1898): this full-figured woman has great presence and sensuality, as does the female in the nearby painting Man and Woman (1898). Many have intuited this is an Adam and Eve representation, but does the woman represent temptation or original sin? Who can say with any certainty? I would like to think of these as celebrations of the female form. They are vivid and vibrant, even if their feminine powers prove too much for the crouching male figure in the latter painting, who seems to be holding his head in despair.

Edvard Munch. Marie Helene Holmboe, 1898. Oil on canvas, 116.5 x 117 cm. KODE Bergen Art Museum, The Rasmus Meyer Collection.

The last painting in this sequence is also from the late 1890s: a portrait of Marie Helene Holmboe, the wife of Munch’s childhood friend Halvard Stub Holmboe. She is sitting comfortably in her chair, leaning to the right, face lifted but eyes gently drifting downward as if in pleasant contemplation. Munch painted more than 200 portraits in his lifetime and was noted for his sympathy and interest in his subjects. As a viewer, you sense Munch’s liking for this woman, not least in his happiness to show her in gentle repose and at ease, rather than putting her in some more performative or aspirational stance.

It is good to see this painting in its restored state. Our Bergen tour group was able to see it mid-restoration in the conservation studios of the Kobe, one half of her face still obscured by layers of dirt and yellowed varnish. Munch did not varnish his paintings, but museums tended to do so, thinking they were protecting them. Years of yellowing have done no favours to many of his works’ light-oriented expositions. It is thanks to the collaborative partnership between the Courtauld and Kobe – the former last year lent the latter a group of Cézannes for exhibition – that a major programme of conservation and restoration was made necessary and possible, in order for these works to be moved abroad. Some of that work revealed the paintings to be in far too fragile a state to travel. Munch – who often put his paintings outside to “weather” them – was always experimenting with different techniques, often to the detriment of his works’ longevity. Maybe that fragility is what has ultimately led to a diminished representation here, and the overrepresentation of the lesser or more exploratory works.

I only hope that, for those not familiar with Munch’s wider oeuvre, this somewhat patchy presentation doesn’t put them off rather than entice them to find out more.