Hauser & Wirth, Somerset

26 June 2021 – 3 January 2022

by JOE LLOYD

In 1983, Eduardo Chillida (1924-2002) bought a derelict 16th-century country house in the hills above San Sebastián. The Basque artist intended to use it for oxidising his metal sculptures, to give them their rich orange hues. But after Chillida started to store his work there, the Chillida Leku (Basque for “space”) gradually became a museum. The couple acquired 11 hectares of the surrounding land, in the process creating a sort of sculptural Eden.

[image1]

For those unable to travel this summer, Hauser & Wirth has the next best thing: a survey of Chillida’s sculptures and works on paper, spread within the barns and grounds of its 17th-century Durslade Farm in Somerset. The farmhouse’s stony walls and expansive gardens are almost a British equivalent to Chillida’s Atlantic paradise.

Chillida is best-known for his large-scale weathered steel sculptures, which occupy public and private spaces the world over. They are heavy, hulking things, generally abstract. Chillida was obsessed with the order and form of baroque music, especially that of JS Bach and, during his lifetime, was beloved by philosophers including Martin Heidegger and Gaston Bachelard. But for all his intellectualism, the experience of his sculptures is strongly physical, a synthesis of material, form and process.

[image8]

They can be difficult to penetrate. One key is found in a yet-to-be-realised masterpiece. In 1985, Chillida conceived Tindaya: a humongous artificial cave to be excavated from the mountain of the same name on Fuerteventura in the Canary Islands. Intended as a monument to tolerance, it would be one of the largest underground caverns ever constructed. Skylights would illuminate the surface of the stone and allow visitors to gaze at the sky above. Tindaya sounds almost the opposite of traditional sculpture and Chillida’s other work – emptying space rather than filling it, creating a form defined by what is not there rather than what is.

[image5]

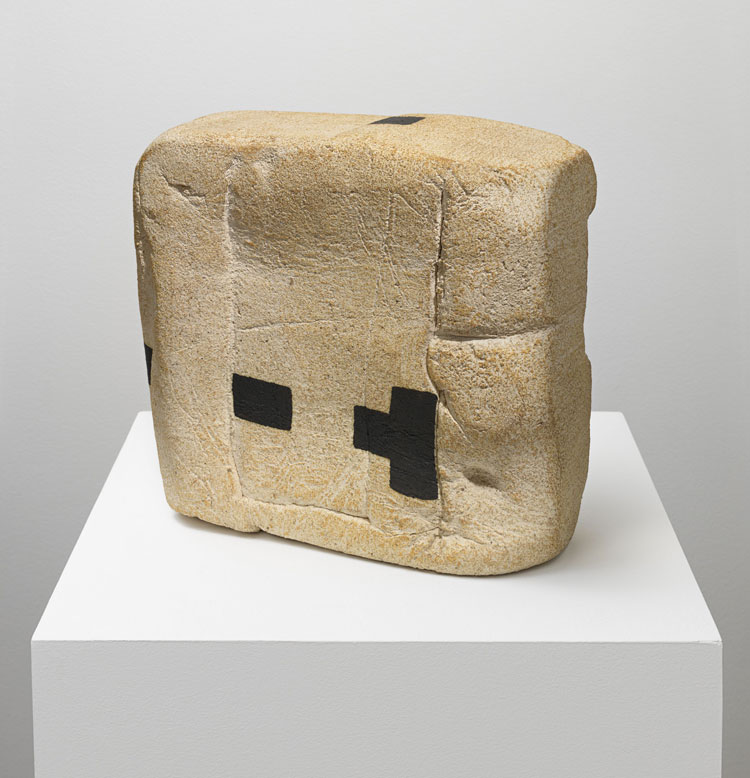

Yet exploring his works at Dursdale, it becomes clear that Chillida was interested in absences as much as in presences. It is perhaps most overt in the smaller pieces, which show Chillida at the height of his inventiveness. One piece in steel, Proyecto para un Monumento (Project for a Monument) (1969) superficially resembles one of Kazimir Malevich’s Arkhitektons. But rather than a thrusting white form bedecked with additions, Chillida’s work is cool, low and earthy, defined by its apertures, including a cave-like recess at the centre. A pair of 1970s works from Chillida’s long running Lurra (Earth) series in chamotte clay feature solid rectangular blocks broken by crack-like seams, which appear pitch dark against the warm orange of the clay.

[image9]

All sculptors are interested in material, but few can have had such an appetite for exploring them all as Chillida. His earliest works, produced while living in Paris in the late 1940s, were largely in plaster. When he returned to the Basque Country in 1951, he started using almost entirely natural materials, a tribute to his verdant, mountainous homeland. He liked to get his hands dirty, opening a foundry where he would take part in pouring and processing his works.

[image10]

Chillida’s appetite for trying out new substances was enormous. The 24 sculptures at Hauser & Wirth span bronze, plaster, iron, steel and Corten steel, granite, limestone, wood and the aforementioned chamotte clay. He had a connoisseur’s eye for them all. Harri VI (Stone VI) (1996), a large-scale piece with a surprising feeling of lightness, is carved from an exquisite piece of pink granite that Chillida bought after coming across it on a holiday in India. He ordered the last 35 blocks from a closing quarry. The Corten steel of Elogio del Cube, Homenaje a Juan de Herrera (1990) has a craggy, pockmarked face that feels a million miles from, say, Richard Serra’s slick, perfectionist cuts of the same material. This was driven by his desire to reflect the traditional manufacturing processes of the Basque region. It has the effect of making Chillida’s work seem particularly tactile and inviting. Many of his outdoor works were designed to be touched and felt, to be positioned in relation to the human body.

[image3]

Chillida began as a figurative sculptor. The earliest work here, Forma (Form) (1948), is a minuscule bronze of a truncated torso with a clear Grecian influence. By the time of the plaster Yacente (Recumbent) (1949), however, he had started to dramatically simplify things. His figure’s head has become an almost perfectly rounded ball, with two cylindrical arms, like forms from Paul Nash’s Equivalents for the Megaliths (1935). The plaster has been worked into a mottled texture, clearly handmade yet reminiscent of a natural cliff face. Chillida’s idiom quickly developed away from straight representation, but many of his ostensibly abstract works feature an element of anthropomorphism. The fantastic Begirari III (The Watcher III) (1994) consists of a horizontal slab of steel appended to a stalk-like tower with an eye-like aperture, like some giant surveying a desert.

[image7]

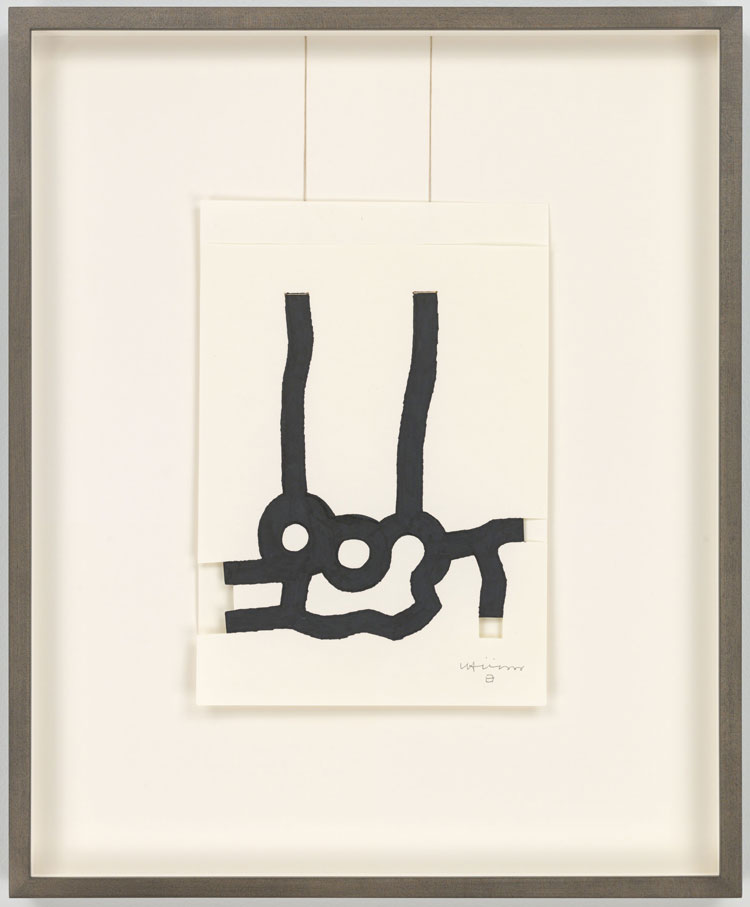

According to Mikel Chillida, the artist’s grandson, each of Chillida’s numbered series was an answer to a particular question. One question that seems to be asked throughout is how to transform terrestrial elements into impossible, gravity-defying forms. His larger works sometimes appear to float above the ground, despite their bulk. He had a lifelong aversion to right angles. The iron miniature Lotura VIII (Knot VIII) has a twisting form that seems to mock the laws of physics, iron tendrils bent into each other. Lurra G-38 (Earth G-38) (1984) features a tangle of writhing tubes atop a Turkish delight-shaped cube. Made from near-black chamotte clay with white speckles, it appears as if, at any moment, it might fall apart and crumble into sand.

[image6]

Before he was an artist, Chillida trained as an architect, and before that he was a professional footballer, playing goalkeeper for San Sebastián’s team, Real Sociedad. Pieces such as Consejo al Espacio IX (Advice to Space IX) (2000) seem to bear both an architect’s precision with substances and volumes and an athlete’s propensity for swift, but controlled movement. It also seems to exist beyond its physical confines, reaching out into the space around it. In an exhibition laden with quiet miracles, it almost looks like an exclamation.

[image2]

![Eduardo Chillida with Lo profundo es el aire, Estela IX [How Pround is the Air; Stele IX], 1989. Granite. Photo: Jordi Belver. © Zabalaga Leku. San Sebastián, VEGAP (2021). Courtesy of the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser & Wirth.](/images/articles/c/026-chillida-eduardo-2021/10.jpg)