Tate Modern, London

20 November 2019 – 15 March 2020

by BETH WILLIAMSON

This fascinating exhibition of work by Dora Maar (1907-97) is extensive, digging in to every aspect of her long career, and full of surprises. Originally trained in the applied arts and painting in Paris, Maar turned to photography in her early 20s. Taking advantage of the interwar rise in advertising and the illustrated press, Maar’s photographic career began with commercial assignments in fashion and advertising, and she travelled to document the social conditions she found in many different countries. Her inventive approach to photography produced a body of images that came to command a significant position in surrealism.

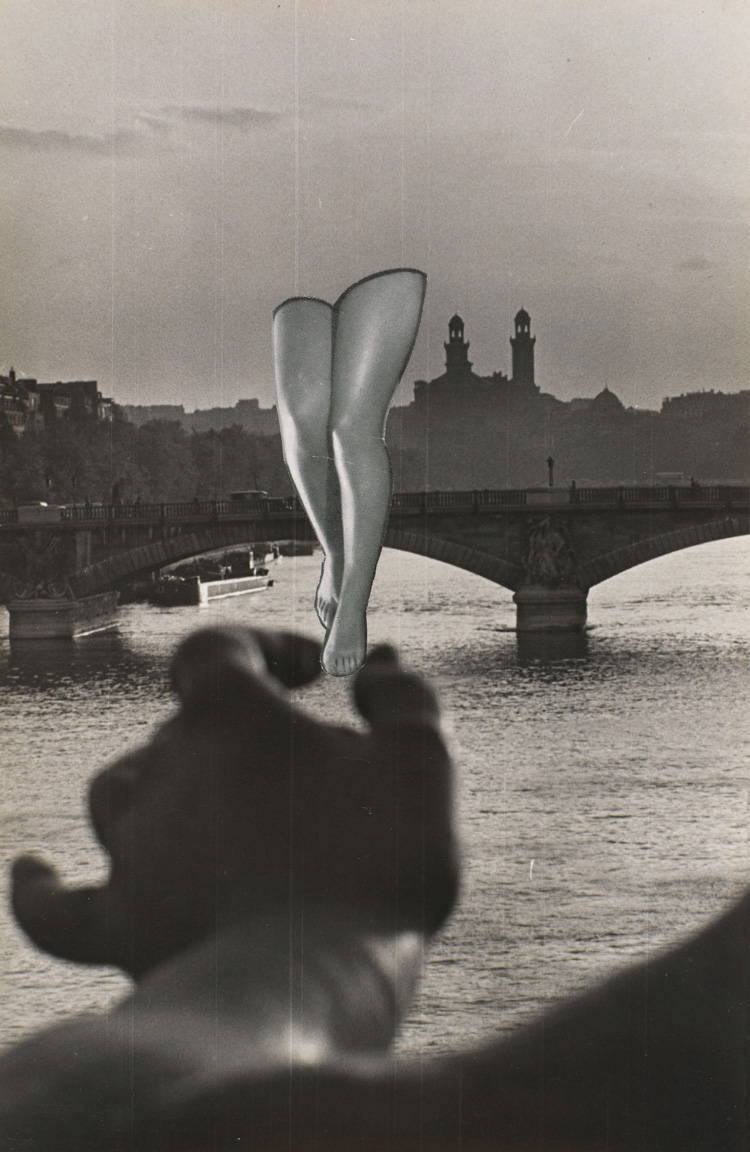

In 1930, Maar shared a photographic darkroom with the French-Hungarian photographer Brassaï. She also worked with the fashion photographer Harry Ossip Meerson. In 1931, she established a studio near Paris with the director and designer Pierre Kéfer. The pair specialised in portraits, nudes, fashion and advertising and, although their prints were signed Kéfer-Dora Maar, Maar was normally the sole author. Their first known fashion commission was for Heim magazine in 1932. It was not until around 1935, when their partnership ended, that Maar set up her own studio in central Paris. Her fashion commissions rocketed and she won commissions from Chanel as well as regular work from designers such as Elsa Schiaparelli, Jeanne Lanvin and Jacques Heim. Her innovations during this time included collage, darkroom experiments and ingenious photographic staging. For instance, the photomontage The Years Lie in Wait for You (1934), probably produced to advertise anti-ageing cream, printed two negatives as one – a spider’s web and the face of Maar’s friend the French surrealist Nusch Éluard.

[image2]

Europe’s economic depression of the 1930s was Maar’s other subject. Beyond the fashion shoots and advertising, she developed a documentary mode to record the social and political conditions she witnessed. Travelling without a specific assignment or commission, Maar was more driven by political conviction. In Barcelona, Paris and London, she recorded economic hardship and political struggle. In 1933, she travelled to Barcelona and the Costa Brava in the northeast corner of Spain during the time of the Second Spanish Republic. In 1934, she journeyed to London and photographed the inhabitants of the East End, the City of London and other locations, including the Pearly Kings and Queens and lottery ticket sellers among her subjects. In Paris, Maar photographed the 40,000 strong community of “La Zone”, an undeveloped 34-kilometre strip of land on the Parisian outskirts. Maar’s political allegiances led her to sign André Breton and Louis Chavance’s Appel à la lutte (Call to the struggle), a manifesto responding to rightwing riots. She was also involved with the anti-fascist Contre-Attaque (Counter Attack) and photographed Groupe Octobre, a leftwing theatre group.

[image3]

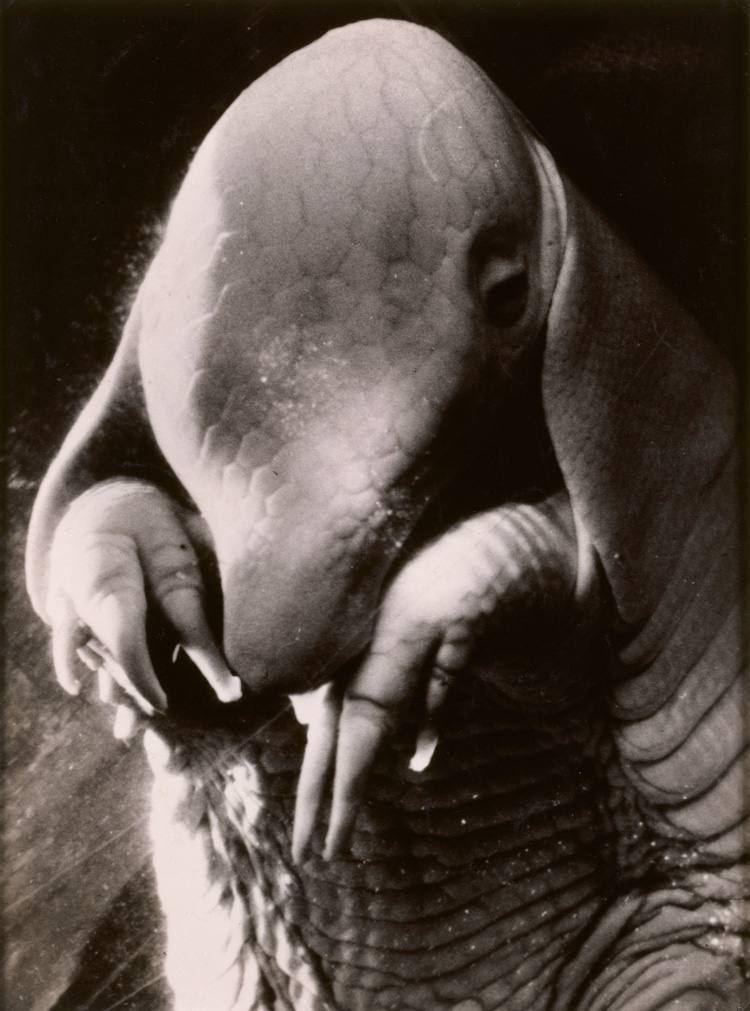

Maar was close to the surrealists who aimed to radically change society and human experience, favouring the role of the unconscious mind over rational thought. Alongside like-minded poets, writers and artists, Maar transformed her documentary photography, deploying dramatic angles and cropping to produce images such as Untitled (Man looking inside a sidewalk inspection door, London) (c1935). Soon she began to use the approaches and themes preferred by the surrealists and sleep, eyes, the sea and the erotic all began to feature in her work: she was one of the few photographers to be included in important exhibitions of surrealist work in the 1930s in Paris, New York, London and elsewhere. In Portrait of Ubu (1936), for instance, she confounds our understanding of reality with an extreme closeup of an unknown creature (widely believed to be an armadillo foetus), making the familiar strange. This deeply unsettling image became a central one for surrealism and appeared in the surrealist exhibition at the Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris and the International Surrealist Exhibition in London, both in 1936.

[image4]

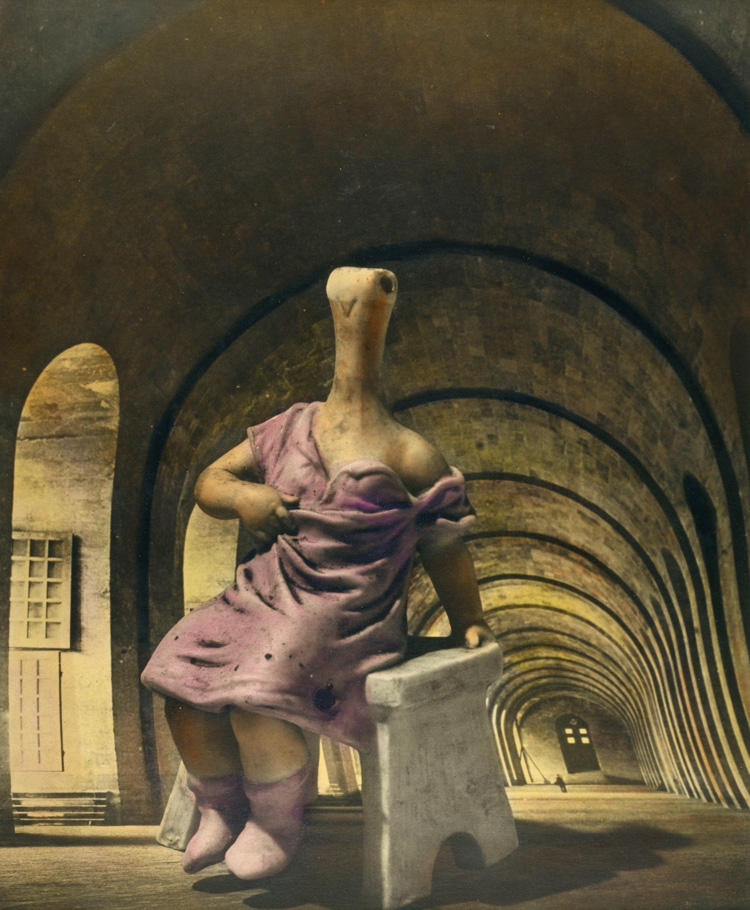

Meanwhile, photomontages created new worlds for surrealists. In a double twist, Maar sometimes created photographs such as 29, Rue d’Astorg (c1936), one of her most famous works, which appear to be photomontages. In this still-life composition staged in her studio, she positioned a headless figure against a print of the vaults of the Orangery at the Palace of Versailles and hand-coloured the final print.

During the winter of 1935-6, and at the peak of her career, Maar met Pablo Picasso. She taught him cliché verre, a photography and printmaking technique, and he encouraged her to return to painting. Maar produced flattened portraits such as The Conversation (1937) that hint at Picasso’s influence, although her painting style was yet to further develop. Also in 1937, Maar documented the making of Picasso’s monumental work Guernica and her project was published in the art journal Cahiers d’art and Picasso repeatedly portrayed her as the Weeping Woman.

[image5]

Maar moved to a new Paris studio in 1942, a move that marked a different direction in painting. Now she painted landscapes and still lifes. The muted palette she used at this time may suggest something of her personal difficulties in the early 1940s, including the sudden death of her mother and her friend Eluard. From 1945 Maar divided her time between Paris and the South of France where her friendship with the poet André du Bouchet flourished. They collaborated on his collection Mountain Soil (1956), which included etchings by Maar and heralded another change in her creative direction. Working in ink, oil and watercolour, Maar began to make gestural impressions of the natural world and paintings such as La Grande Range (c1958) attracted critical acclaim.

In a return to photography in her later years, Maar lost interest in the outside world, saying in 1994: “The street has changed so much, don’t you think? It’s more extravagant … but at the same time its not interesting any more, it’s banal.” Instead, she focused her investigations in the darkroom. Experimenting with cameraless photography, she made photograms by placing objects directly on to light-sensitive paper or by drawing light across the paper’s surface. The now-reclusive Maar may no longer have cared for the outside world, but she continued in creative experiment, finding new ways to make ideas visible.

[image6]

The vast array of materials, methods and techniques that Maar engaged in over her long career is well represented in this expansive exhibition and it is inspirational. We see the various shifts in her career not only as personal artistic development but as pragmatic, too. At the very beginning of her career, commercial photography was an extremely sensible move – she wanted to work and that is where the work was to be found. Throughout the years and the twists and turns in her interests and practice, she collaborated with other photographers, artists and poets in different ways. In the end, she returned to photography and an almost hermetic mode of practice that enabled her to continue creating, despite her preference for remaining in the studio. In an incredibly long and fruitful career that we now know was not always properly attributed at the time, this exhibition begins to correct some misapprehensions. We also get a sense of Maar as a strong independent woman artist finding her own preferred mode of working, largely despite the influences around her rather than because of them.

-c-1935.jpg)

.jpg)