by ALLIE BISWAS

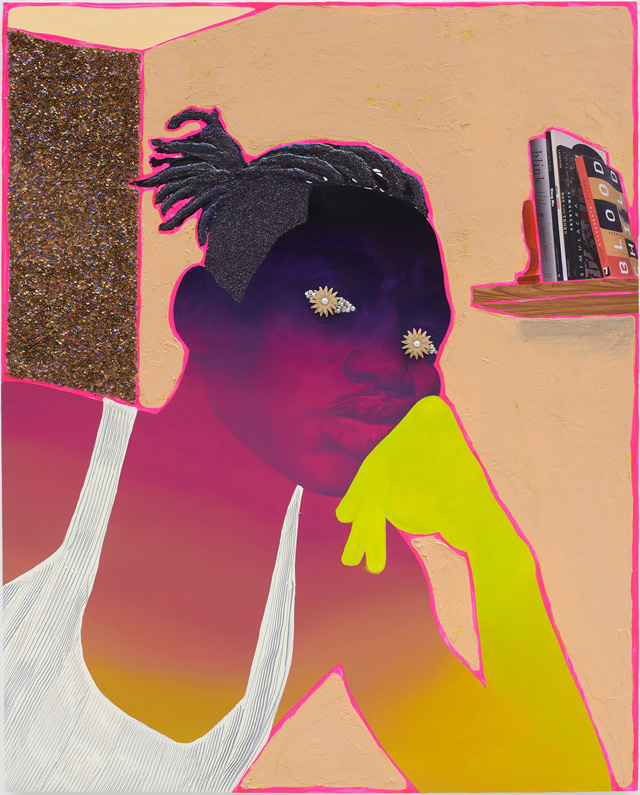

With two solo exhibitions opening this month in New York and Chicago, and a recent institutional debut at the Andy Warhol Museum, Devan Shimoyama’s paintings have been reaching wide audiences across the United States – and have been quick to gain a following. His vibrant pictures, which often incorporate fabric and costume jewels, explore the politics of queer culture within the context of black American life, and often use self-portraiture as their starting point. Narratives inspired by old masters, such as Caravaggio and Goya, have also become a sustained source material.

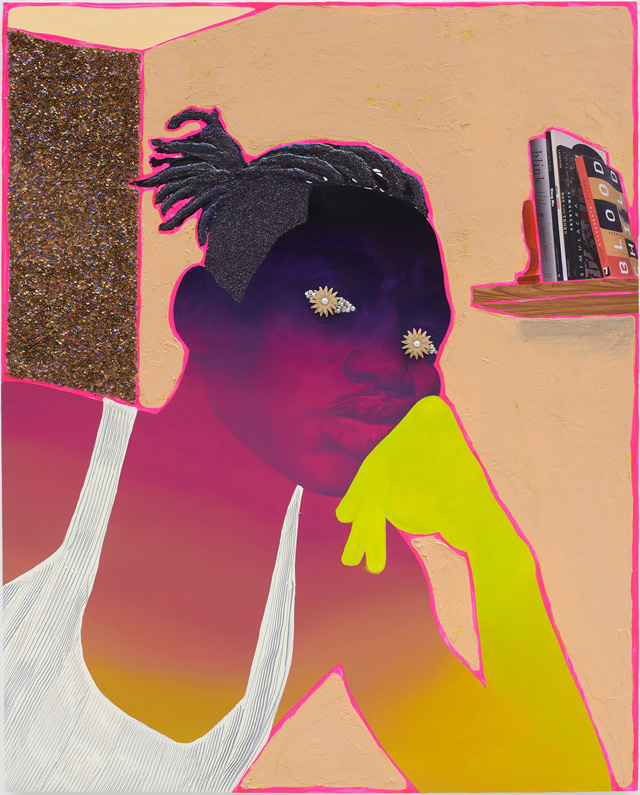

This month, Shimoyama is presenting a new series of paintings, Shh …, at De Buck Gallery in New York, which think about how an understanding of oneself can be constructed through literature that exists outside mainstream canons. The show at De Buck coincides with We Named Her Gladys, the artist’s first solo exhibition at Kavi Gupta in Chicago.

Shimoyama (b1989, Philadelphia) graduated from Yale University School of Art in 2014 and is a professor of art at Carnegie Mellon University. He lives in Pittsburgh.

Allie Biswas: Your recent paintings draw on black masculinity, particularly in the context of queer culture. Self-portraiture is also an important part of your work. Can you talk about the role that personal biography plays for you, and how that became a substantial (and long-standing) source material?

Devan Shimoyama: Personal biography and self-portraiture were the most sensible starting points for exploring a multitude of topics for me, considering that I always felt as though, in order to better understand others, one must learn to understand oneself. I use my body to explore magic, mythology, history, intimacy, joy, pain, and so on, and it has really shown me that there are so many other individuals that can relate to the many various experiences I’ve painted about.

[image3]

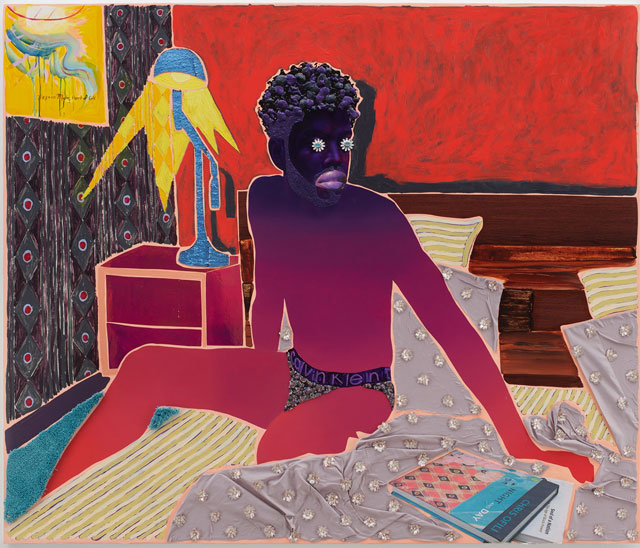

AB: When did you start thinking about how the black male functions in external spaces, and what that world is like? Most recently you have worked on a series that focuses on the barbershop, and you have revised perceptions of that space, which has a longstanding reputation as a positive, welcoming environment within the African American community.

DS: The barbershop series really expanded my practice into thinking more broadly about blackness, masculinity and queerness, and where all of that intersects. I was hanging out with two close friends of mine who identify similarly to myself – black and queer – and we all sympathised with the experience that one of us had to deal with when going to the barbershop. One of those friends decided to grow his hair and have it in locs, and now often goes to a salon to have his hair tended to and maintained by, predominantly, women. The other now gets exuberant weaves and braided styles instead of going to the barbershop. That sparked something in me that helped to ground my work into a more realistic setting.

I felt many individuals possibly shared similar sentiments, especially after seeing the Kerry James Marshall retrospective [at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 2017] in which several people were looking to a painting from the early 90s as though it was something that was indicative of black culture at large, even today. As iconic and important as that painting is, it felt as though there was this missing component of intersectionality: how barbershop environments have shifted over the decades – as well as this notion of male fraternal bonding occurring – seemed almost ludicrous to someone who identifies as queer in some capacity. I made the barbershop series not so much to point a finger at anyone in particular, but as a way, hopefully, to start a dialogue and speak from my own point of view in those spaces. It is about what I hoped such spaces could have the potential to become.

[image4]

AB: I also think about your painting Weed Picker, which is part of a new body of work that explores the idea of black ownership – black people claiming and cultivating their own spaces. Though these ideas seem to relate to black identity politics and race more generally in the US, rather than the specificity of queer experiences.

DS: Weed Picker came about when thinking about the significance of me buying a home recently, this being something that my grandparents worked their entire lives to do, yet so many young people, and, in particular, black people, don’t even consider. Yet these are the people who suffer the most from gentrification and are so easily displaced from the communities and neighbourhoods they cultivated for themselves. In that painting, Weed Picker, I’m wearing a shirt with the four lead female characters’ names from the 90s sitcom Living Single, a nostalgic reference for myself when reminiscing on this fantasy presented by a group of black individuals living with each other and dealing with their own subset of issues and events among others that look like them.

AB: On the subject of race in the US, I wanted to discuss two works that feature in your show at the Warhol museum, which memorialise or mourn the deaths of Tamir Rice and Trayvon Martin. I mention these works also because, thematically, discomfort or hostility is often addressed through your subjects. What complicates this is your aesthetic, which, particularly in your paintings, suggests what might traditionally signal the opposite of sorrow: a vibrant palette, luscious materials. Could you maybe say a little about this contrast, if it can be called that?

DS: I think this contrast is significant because, for me, I don't think that beauty and pain are so separate. I often find myself noticing how communities deal with pain, trauma or death. Or even how individuals deal with those things – through art, music and so on – and in the object-based works dedicated to the loss of Tamir Rice and Trayvon Martin, I’m not doing anything different from what many people do amid dark times, such as making spontaneous memorials. Black people deal so much with trauma and hurt on a regular basis, I don’t think reiterating that pain through imagery and more darkness is something I’m interested in doing. Those things function as both memorial and surrogate for the representation of those bodies. Instead of depicting a black body in pain or torment, I’d much rather celebrate those individuals as something more positive and whole.

[image5]

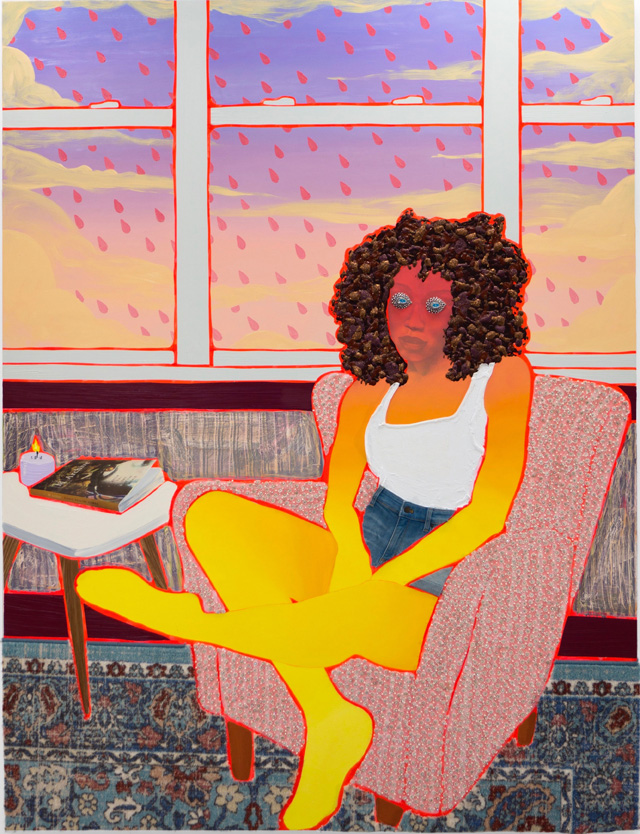

AB: What about the existence of reality and fantasy in your work – paintings of everyday scenarios alongside paintings of constructed scenes that reflect your interest in the old masters, in mythology, in magic.

DS: My approach is pretty consistent throughout all of those varied themes ranging from mythology, folklore, everyday scenes … I think of the everyday scenes as something just as rich in magic and myth as the other works. I suppose the primary differences would be the spaces in which those figures reside; the everyday scenes are much more specific in terms of the spaces, such as the barbershop, inside a home, in the backyard, or standing by a bus stop. I think in these works, I’m exploring the idea of tiny moments of magic being possible in the everyday.

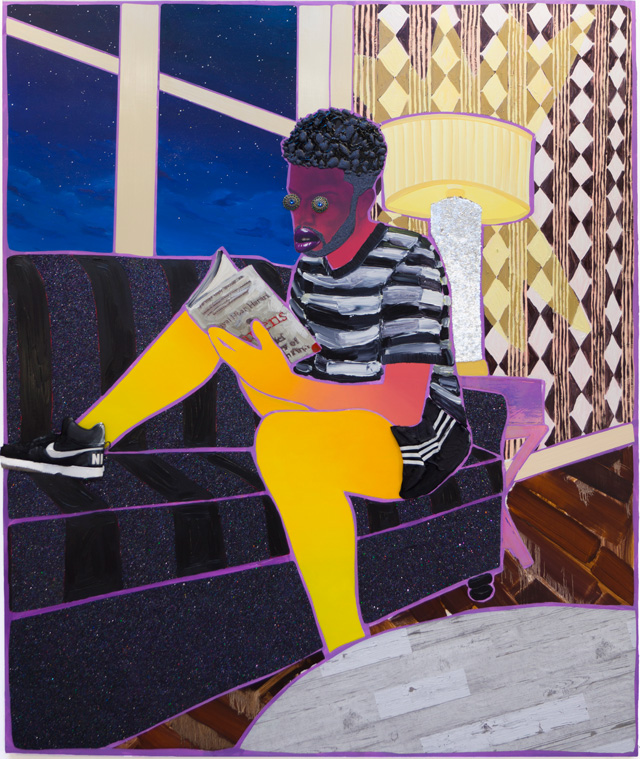

AB: Let’s talk about your current show at De Buck. There appears to be a preoccupation here less with envisaged narratives and more with the self, and how the self can be formed, as well as relayed, through literature. Can you tell me about these paintings?

DS: In Shh …, the works all explore how one can come to construct an understanding of oneself through alternative literary texts as opposed to just cut and dried history, theory or science texts. In the paintings, you’ll find artist books, exhibition catalogues, poetry, prose, science fiction, horror, epic fantasy, history and psychology/sociology texts. In a way, I’m thinking of this body of work as something that will continue to grow and which functions as a reading list of sorts. The work is for people to think about reading as a way in which we can look to all forms of literature to understand our own histories; to see ourselves in genres in which we aren’t typically given starring roles, or speculate about ways in which we can make strides to necessary paradigm shifts.

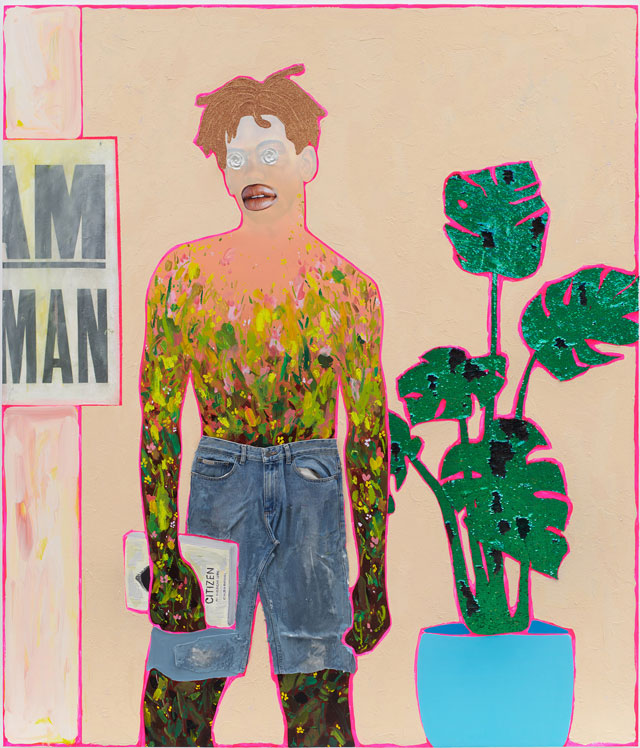

[image2]

Further complicating some of those texts are small things. For example, in the painting titled A Man and a Brother, I’ve included Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen: An American Lyric, which features on the cover an image of a David Hammons piece of a decapitated hood. In the background is a poster featuring the words “I AM A MAN” used in civil rights movement protests. I think conflating these histories through art, poetry, criticism and protest all in one work can show where we’ve come from and how we’re still fighting similar battles even today.

AB: Finally, I wanted to touch on your show at the Warhol museum. I am interested by this collaboration of sorts; works by two artists which seek to highlight black and Latino transgender culture and drag queens. When did you first encounter Warhol’s body of work Ladies and Gentlemen, and can you tell me how your paintings of Miami drag queens came into being?

DS: I had seen a few images of the Ladies and Gentlemen series before when looking into Warhol’s work, but had never seen them in person, nor did I know the full story behind that commission until working with Jessica Beck, who curated my solo show at the Warhol. She had a clear vision for curating one of my works into Warhol’s body of work on a separate floor of the museum.

My paintings of Miami drag queens came to life through me being presented the opportunity to be an artist in residence at the Fountainhead Residency in Miami. I decided to use that opportunity as more of an onsite research project of sorts, and what I noticed was that there seemed to be a stark difference between the Miami drag scene and the Miami Beach drag scene.

Much of the materials I use in my work are from the same shops that drag queens find materials to construct their fantasy on to their bodies, so I felt like it was only natural to reach out to some queens there and shadow them for those four weeks in residence. I became fascinated by the urgency in which some of those queens do drag to cultivate community for queer youth people of colour, and, in particular, I was amazed by Miami being a place that was so tethered to the Caribbean, which is a place where blackness is quite a complex identity in terms of how and when someone identifies openly that way.

Being of Trinidadian descent, I felt really interested in how many immigrants identify with their homelands in such specific ways, and when queerness intersects those identities, it causes many people to leave their families and homelands for safety or acceptance. Many of the events I attended in which drag queens and kings were performing fundraised for LGBTQ affordable housing and other amazing initiatives, and I wanted to honour those individuals and all that they do.

• Devan Shimoyama: Shh … is on view at De Buck Gallery, New York, until 20 April. Devan Shimoyama: We Named Her Gladys is at Kavi Gupta, Chicago, from 23 March to 26 May 2019.