The Photographers’ Gallery, London

25 March – 12 June 2022

by CELIA WHITE

Major political and social subjects characterise this year’s selection for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, due to be awarded on 12 May. The prize is open annually to any living artist for an exhibition staged or a publication released in Europe during the previous year, and this year’s shortlist features Deana Lawson, Gilles Peress, Jo Ractliffe and Anastasia Samoylova. While Peress and Ractliffe are known for their work capturing the violent struggles in the North of Ireland and South Africa respectively, their work has surprising resonances with Samoylova’s more intimate depictions of places wracked by the global climate emergency. Lawson’s world, by contrast, is one of her own making – her images depict her family, her friends and the materials and moments that make up a personal history.

[image2]

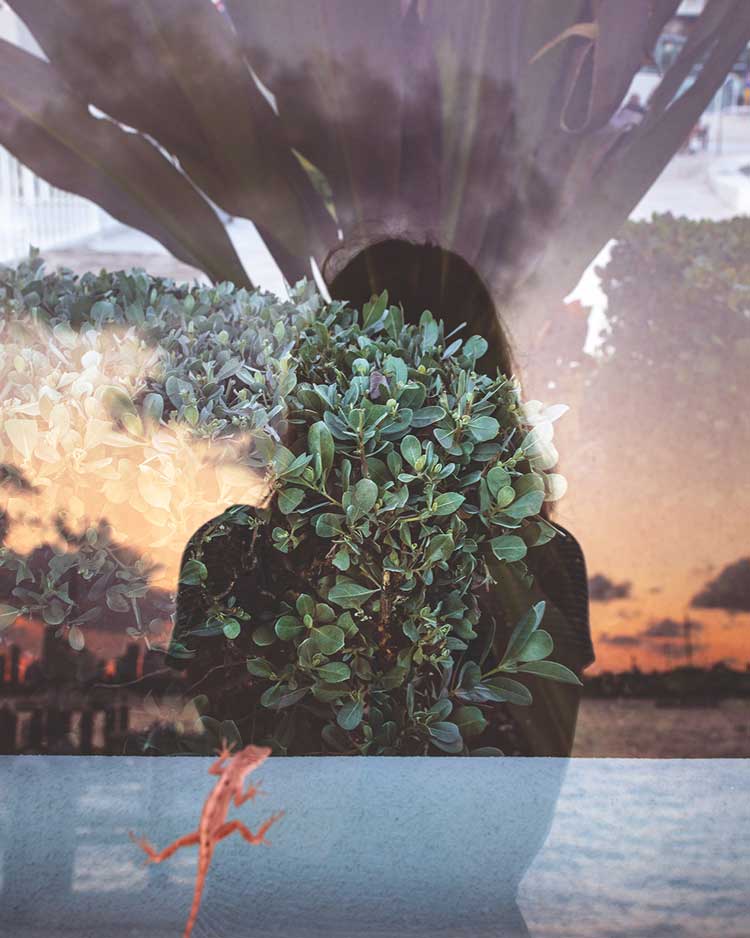

Samoylova’s photographs are, in my view, the strongest in the show. Her aim is to confront the viewer with the climate crisis not as an “abstract threat” but as a lived reality. The exhibition space is painted deep green and purple to mimic the boldly coloured manmade landscape of Florida that is Samoylova’s subject. This intensifies the experience of looking at her photographs – the sense of imminent yet slow-moving climatic doom that emanates from scenes showing windswept palm trees, a lifeless-looking floating alligator, or the roots of a tree entrapped in concrete.

[image16]

Everything in Samoylova’s environment appears pre- or post-drama: an apocalypse on slow boil that becomes incrementally tangible. What looks like a photo of an impressionist painting of cypress trees – a celebration of light, water and verdancy – is in fact the mould and moss that has crept up a brightly pink painted wall as sea levels rise. The stunningly calm image of an arched, tiled folly looking out to the ocean reveals its desolation in the seawater washing in across the floor. Among this disquieting quiet, people live, struggling with flooded streets and humid air. By promoting this tension between crisis and stillness, Samoylova reminds us that experiencing climate change in an abstract way is a marker of luxury in today’s world. Her viewers, and her reviewers, have the licence to think about, care about, and act on the climate emergency at discrete moments – such as in an exhibition – while her subjects must continually negotiate its power and its perils.

[image8]

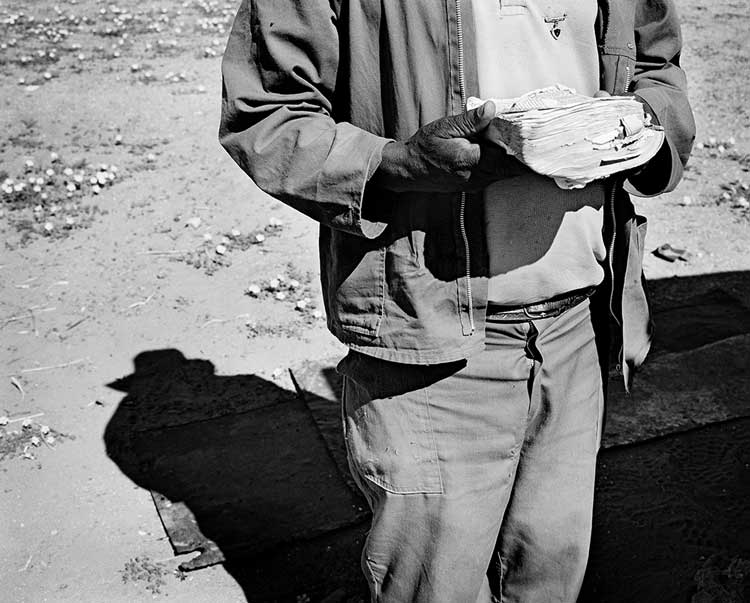

In the transition from Samoylova’s display to Ractliffe’s, we move from too much water to too little. Ractliffe’s black-and-white imagery shows arid, desolate landscapes, donkeys and goats haunting empty expanses, and dried-up plants, trees, birds and swimming pools. Ractliffe presents a muted – often inaccessible – story of the sociopolitical devastation faced by South Africa after apartheid. She offers clues to this history and its impact on the land through depictions of silence, absence and abandonment: a group of suits hangs from a tree, as if recently exited by their wearers, while other images feature a de-miner in a protective suit scanning for landmines, and a collection of rough, unmarked graves.

[image12]

[image13]

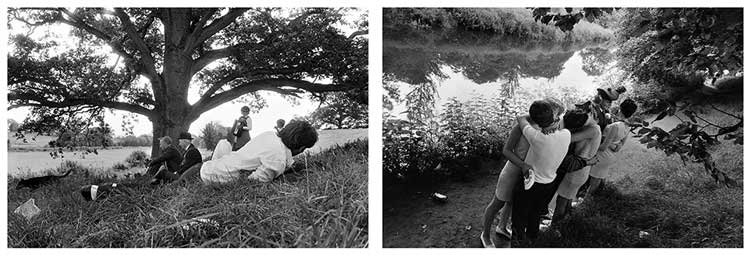

While Ractliffe’s work resonates with the quiet drama of Samoylova’s, Peress confronts the conflict and chaos in the North of Ireland during the Troubles in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. His 2021 photobook Whatever You Say, Say Nothing springs off the walls through a maximalist display of imagery and text. In a similar way to Samoylova, Peress takes a day-by-day approach to the conflict and the many ways that it unfolds. One image shows teenagers kissing next to a burning pyre, as if oblivious to it; in another, men run with guns in hand; another shows a wall bearing graffiti dedicated to Linfield FC, the historically Protestant, loyalist Belfast football club.

Peress’s photographs sit in heavy contrast to the stylised, single-narrative representation of this troubled city in Kenneth Branagh’s recent film Belfast, though they do show the “real” versions of some of its scenes – children running, masked men fighting, burnt-out cars. But Peress’s depiction is multi-perspectival and multi-vocal. Punctuating the imagery are the written chapters that narrate each day’s events in short, anxious sentences (“And what about the dead? How do we remember them? Why did they die? What did they die for?”) while a monumental photograph of one of Belfast’s famous murals faces snapshots of royal wedding celebrations and Orange Day parades.

[image11]

Compared to that of the other three shortlisters, Lawson’s work represents a considerable change in tone. Here we have a personal mythology that is built up through old photographs and staged scenes as a way of reframing Black experience. Emily and Daughter (2015) is a double portrait of two women that has been blown up from a printed photographic original. The subjects look out from behind a pockmarked, paint-spattered surface, the formality of their poses and smiles suggesting this image’s original intended destination in a family album. Taking a different approach to the depiction of family affairs, Monetta Passing (2021) is a studio-style funeral portrait featuring a dead woman in a veil, accompanied by a man who stares tearfully at the camera. Created on a large scale, and in high colour and full focus, this is a contemporary rendition of ritualised grief that is rendered at once individual and typical through details such as the family photographs on the table, the purple silk on which Monetta lies, and the large bunch of flowers that loom beside them.

Taken together, Lawson’s images do hint at the personal mythology that is promised in the curator’s introduction to her display. However, what is shown appears to be a partial selection of her original project at Kunsthalle Basel, and this makes it difficult for viewers to appreciate the many nodes in Lawson’s network of references, motifs and experiences. By contrast, in Samoylova’s work we are drawn in by both the strange and the familiar. She shows us a place where many of us don’t yet live, but the reality of which is more proximal, and less abstract, than we would like to acknowledge. Perhaps the currency of art prizes has waned following the Turner Prizes of 2019, when all four shortlisted artists won collectively, and 2020, when the prize money was divided into 10 bursaries rather than given to one artist. Yet when the jury reveals its pick for the Deutsche Börse prize on 12 May, I will not be surprised if it is Samoylova who prevails.