Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid

29 May – 30 September 2019

by JOE LLOYD

In 1985, David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) was selected to appear in the Whitney Biennial, then as now the closest thing artists in America have to a golden ticket. “When I congratulated him,” wrote his biographer Cynthia Carr, “he had such a look of distress on his face. He told me he hated the art world. And then, I believe the exact sentence went: ‘If I were straight, I’d move to a small town right now and get a job in a gas station.’”

Even if Wojnarowicz felt this avenue of escape possible, it seems unlikely he would have taken it. The grungy streets of 1980s New York seemed his natural habitat, and he thrived as part of an East Village nexus of artists and musicians. After appearing at the Whitney, he continued to make and exhibit art at a frenzied pace, leaving behind a prodigious body of work that suggests an unquenchable itch to create. He painted, photographed, collaged, sculpted, assembled installations and dabbled in film; he fronted a band, 3 Teens Kill 4; and he wrote incessantly. Until recently, however – the turning point may have been a mini-survey in 2011 at the PPOW Gallery in New York – he has often been remembered for two things: his death from Aids-related illness and his role as an anti-censorship activist in the 90s culture war.

[image12]

It goes without saying that there was much more than this to Wojnarowicz, as amply demonstrated by History Keeps Me Awake at Night at the Reina Sofia – a full-bore retrospective exhibiting the bulk of his major work, which debuted last year at the Whitney Museum. It also reveals him as an artist whose concerns remain resonant in the present moment. Wojnarowicz’s art and writings scorch with righteous rage against homophobia, American imperialism, gun violence, child abuse, the patriarchy, advertising, neo-liberal capitalism and organised religion. This anger stemmed in part from his own appalling experiences. Abandoned by his parents when he was two, he was a victim of child abuse and spent several years as a street hustler and sex worker.

[image2]

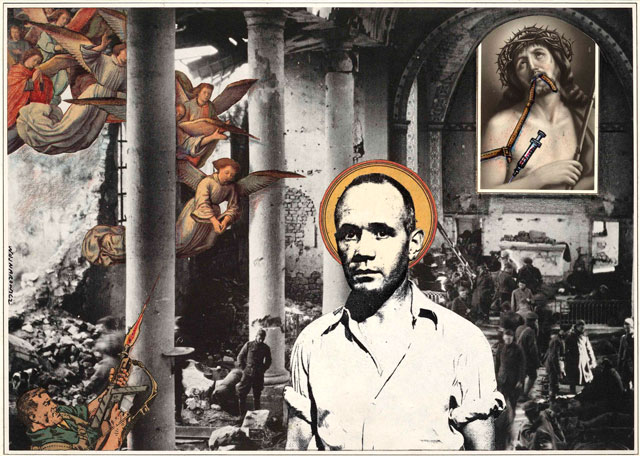

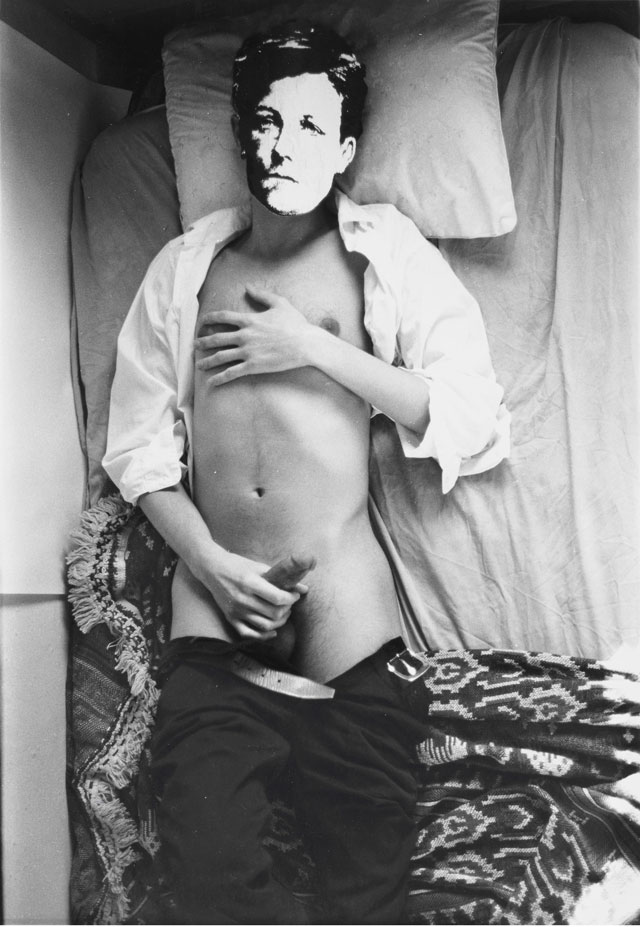

Little wonder that, from the beginning, he defined himself as an outsider. He made collages featuring Jean Genet, William S Burroughs and Joseph Beuys, a trio of outsider heroes. Paramount to the young artist’s mythology was Arthur Rimbaud, the symbolist prose-poet (and self-proclaimed other: “Je est un autre”) who had blazed comet-like over French poetry before choosing to disappear into colonial obscurity. Wojnarowicz’s 1979-80 journal shows the poet masturbating, clothed and unclothed.

[image5]

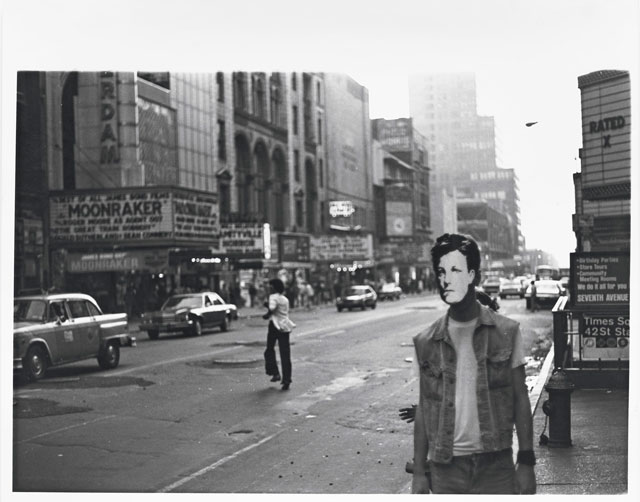

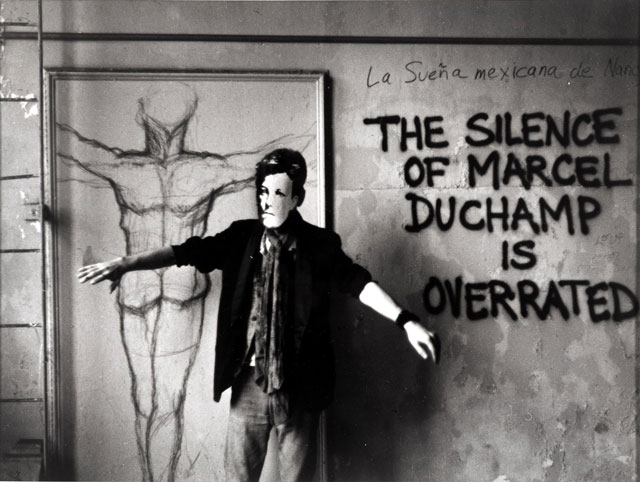

His first major artwork, Arthur Rimbaud in New York (1978-9), involved Wojnarowicz and friends walking around the metropolis while wearing cardboard masks of the poet. At the Reina Sofia, a wall of photographic prints shows “Rimbaud” in a cake shop, an abattoir, pointing at graffiti and hanging around Coney Island. One sees the mask cast down on the dirty ground, a speck of urban flotsam.

[image13]

It didn’t like long for Wojnarowicz to emerge from behind the mask. In 1981, he had a brief romantic relationship with the photographer Peter Hujar, who subsequently became his mentor; an intimate portrait of Wojnarowicz by Hujar captures a wary sort of nerve and a confident seductiveness. A self-portrait from 1983-84, adapted from a photograph by Tom Warren, amplifies this front of self-possession further. The artist stands with folded arms, staring into the camera as if sizing it up. On his right, a map of America overlays his skin, while his left side is fringed with fire; whether he is burning up or emanating flames is ambiguous. A series of tiny clocks run down his right arm, ticking reminders of mortality.

[image4]

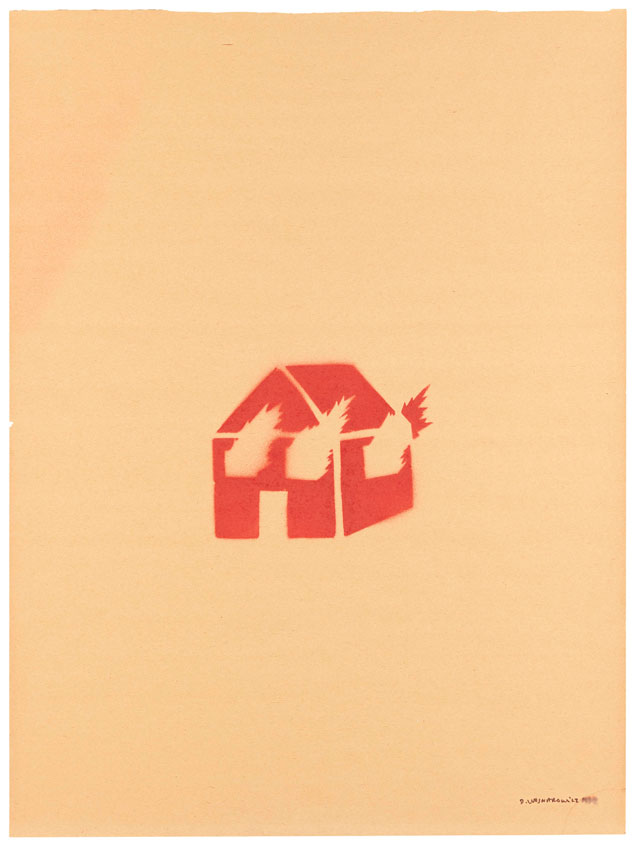

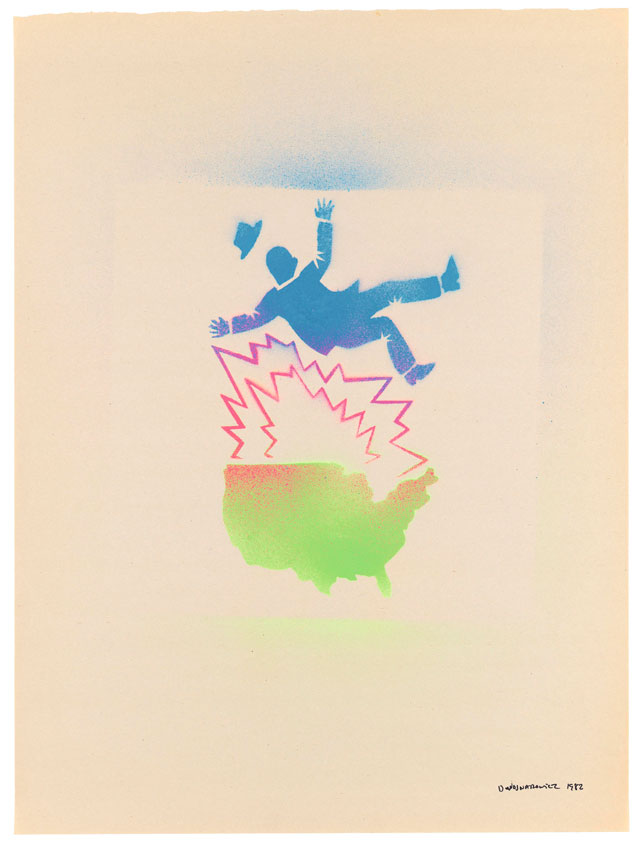

For all the apocalyptic fury of Wojnarowicz’s vision, a compendious display of his studies and works on paper demonstrates a mischievous streak. In 1983, he painted and drew atop posters advertising mass-market produce. The police invade Meat Franks, a gunman is shot in the hand over Sirloin Steaks, and a man sticks his head in a horse’s rectum above Jumbo Rolls. A collaboration with fellow scenester Kiki Smith has comic strip-esque figures arranged around a Rorschach splotch. There are disembodied heads redolent of Jean-Michel Basquiat, floating over text. Best of all are a set of minute images created with stencil, which Wojnarowicz developed to spray-paint on to buildings. One shows a house on fire, another a man crisscrossed with a jet plane. A third shows a man launched explosively out of the US, rejected – or ejected – by his home country.

[image7]

From these early works, Wojnarowicz developed a vocabulary of symbols that would recur throughout his career. The disembodied heads, for instance, were repurposed for Metamorphosis (1984), a series of collaged busts that were originally displayed as if they were targets in a shooting range. One of them is gagged, as if awaiting execution. The painting Hujar Dreaming (1982) has the stencilled form of the older artist atop a world map. Above, Wojnarowicz sprayed-painted in black four targets, a church, a soldier, a needle, a bottle of alcohol, a television, a falling man and, outlined in red, a demonic animal head. The spread may represent Wojnarowicz’s hinterland as much as it does its ostensible subjects. Hujar’s form itself was repeatedly morphed and reused, most strikingly in the acrylic on Masonite Green Head (1982), where it appears both entire and shattered into pieces, like a glass lamp hit by a bullet. Soldiers crawl around the space where Hujar’s head was, camouflaged reminders of the militarism implicit in US society.

[image9]

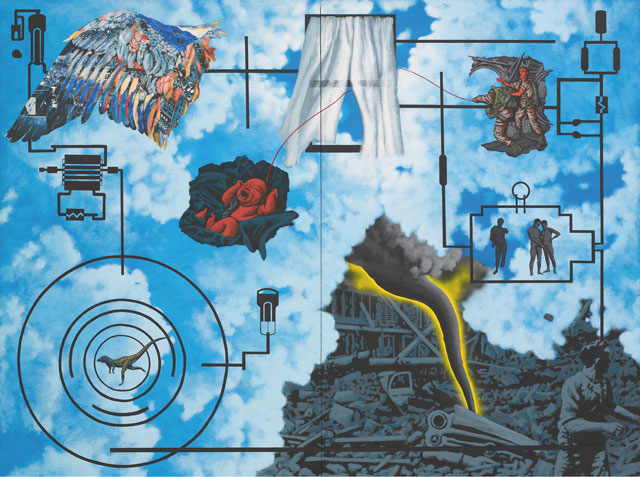

These concerns were magnified in the mid-80s, when Wojnarowicz embarked on a series of large-scale paintings that feel as if conceived as magnum opuses. They instead represent a nadir: glorifying in their own garishness and collapsing under the weight of their stacked symbolism. The work that lent the exhibition its title, History Keeps Me Awake at Night (for Rilo Chmielorz) (1986), is a case in point. The sleeping Hujar appears yet again, but here he lies beneath a wall of dollars, the outline of a cartoon gunman, a fallen Doric column, a wagon wheel and a comic book alien, among other clutter. Arresting the momentum of an otherwise exhilarating exhibition, these busy paintings suggest Wojnarowicz as an artist at his best when operating within constraints.

[image14]

Hujar died in November 1987 from pneumonia, less than a year after being diagnosed with Aids. A trio of photographs of his head, hands and feet, taken by Wojnarowicz on the day of the artist’s death, remain almost unbearably harrowing. Wojnarowicz was diagnosed with HIV a few months later. The art of his final years saw him pull back from painting and into photography and collage. Images that clashed in the paintings gain new vitality when transferred in medium. Spirituality (For Paul Thek) (1988-89), a set of seven stills from the unfinished film project Fire in the Belly, has the familiar dollar bills, clocks and reclining figures, but as discrete snapshots rather than crudely arranged. Even in illness, he still had a playfulness: the Sex series (1988-89) saw him montage pornographic images on to New York landscapes, as if zoom-in inserts showing the private entanglements that lie behind the city’s doors.

As the end drew closer, Wojnarowicz devoted more and more of his time to writing. The memoir-cum-essay collection Close to the Knives (1991) is his masterpiece, expressing in hallucinatory, incendiary prose much that his paintings had failed to do. These writings in turn were excerpted and inserted into other works, such his 1990 quartet of Flower paintings, which demonstrate a far more refined practice than the works of a few years earlier, as well as a melancholy that intensifies his career-long rage.

[image16]

Two very different works close the exhibition. Both return to the image of the artist himself. Untitled (One Day This Kid …) (1990-91), perhaps Wojnarowicz’s most famed work in his lifetime, despite only appearing in a catalogue, sees a gawky childhood photograph of the artist surrounded by a text that enumerates the numerous prejudices and calamities that will befall an adult by virtue of his sexuality; its power remains undiminished, today serving as warning of how easily rights and freedoms can be lost.

[image15]

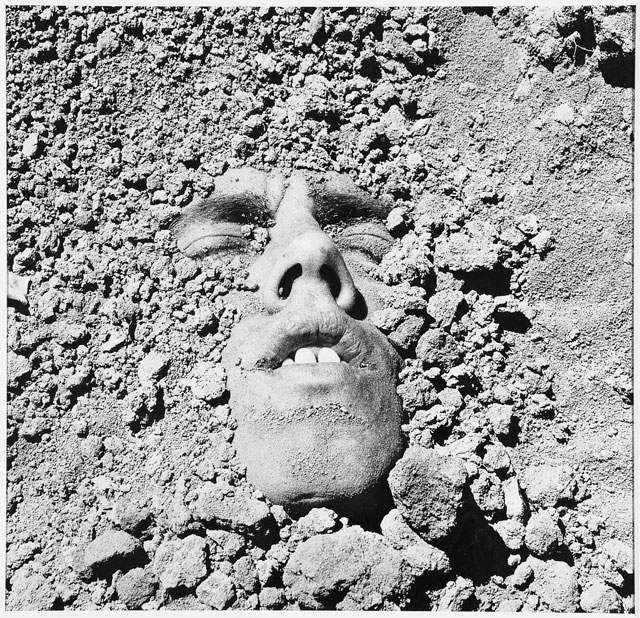

The photograph Untitled (Face in Dirt) (1991) shows the adult artist’s visage part-emerging from the soil and stones of Death Valley, eyes closed, teeth defiantly flashed. He may be buried, but he will remain slumbering beneath the soil, waiting to return. Thanks to this exhibition, Wojnarowicz has re-emerged, shaking away the dust, as an artist for our times.