Gagosian Gallery, London

2 November-9 December 2006

David Smith: Sculptures

Tate Modern, London

1 November 2006-21 January 2007

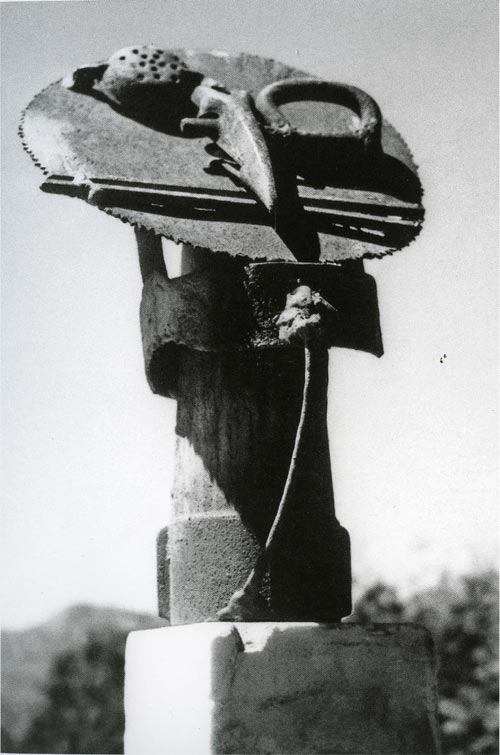

Smith left a legacy of as many as 600 works. Significantly, two exhibitions are currently celebrating this in London. One is at Tate Modern until 14 January 2007 and another is at the Gagosian Gallery, but only until 9 December, and concentrates on his 'Personage' series, which many would claim, represents a broad summit of his art. Smith chose this title astutely, where a combination of the best aspirations of 'assemblage' with that of personality were expressed. These works are certainly figures, but they never quite become actual individuals - and deliberately so.

At Tate Modern, the big show opens with 'Sawhead', typically made up of disparate elements: a strainer, shears and the flat blade of a circular saw, replete with all its sharp serrations: this profile is highly disjunctive to the eye. Further on in the show, he assembles varied job lots of car parts, such as bits of boiler, iron rods and clear sheets of steel, rising as high as 10 feet. A construction of the steel, entitled 'Cubi', is a climacteric piece that Smith was still working on when he crashed. Works from the 'Cubi' series were then to be much sought after by dealers as a piece, which would range off the Richter scale in terms of price when Smith was killed.

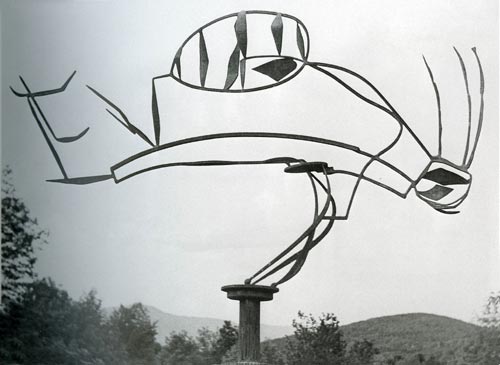

However, on the whole, there is less emphasis in the Tate show on such heights, but rather an attempt to create a balanced assessment through a carefully chosen selection of works (many of which the Tate has built up in its own collection over the years). This allows a clear and retrospective assessment of the whole oeuvre. Interestingly, Smith is revealed as 'taking a line for a walk' and, in a wholly sculptural sense, this is something never achieved by others so dramatically and poetically as in his work. But in this way, Smith shows a few affinities to ideas developed earlier by Picasso and by Julio González in Europe, yet never so much as here, when Smith's work catches all the graphic potential of a line. Smith uses stretches of metal to convey facial elements, in this plundering of physiognomy to find the nose, the eyes and even to parody a raised eyebrow. Smith's secret here was that he helped the viewer into the piece, from behind, so to say, peering out from behind the eye socket.

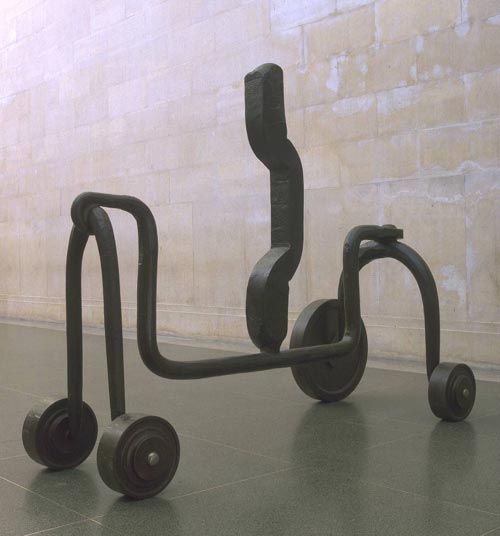

In Smith's work there is an inherent, almost agricultural shed ethos, where items get selected from piles of rejects, to be reborn as living sculpture. This later tendency expanded considerably when Smith was enabled to move out to a farm he had acquired in the country.

One cannot perhaps say that the 'Personages' series themselves, here intelligently presented as a separated group of sculptures, truly represent a high point. These works, assembled by the Gagosian Gallery here in London, all wear individual identities, as has been pointed out above. But they represent an alternative strain of Smith's thinking, with figures skilfully collaged. They do possess a symbolism more powerful that anything offered by the highly versatile Sir Anthony Caro. The resonance here refers, of course, to the work of González, plus an inevitable familiarity with the sculptures of Picasso. But there is a difference. For Smith, the welding process in his work was definitive of the structure of the works as they stand, but also of the basic materiality. For Smith, the sculptures never lost their first affinity with the upstate landscape, based naturally enough on an instinctual referencing, but never forced through. Which is something one cannot say of Caro, however skilfully the works are put together. For Caro, working with Henry Moore can only in retrospect be seen in the long term to be an unwitting handicap, whatever the 'kudos' of the connection, and very different from the real life on a rundown farm. So we find Smith truly earthed in his landscape.

It is clear that Smith is an artist who is as fundamentally American in that special, take it or leave it way, as was say Jackson Pollock, or even (in quite a different way) Edward Hopper. Such great American artists wholly and authentically do represent their culture in that indigenous, non-metropolitan way and from the shed or the barn, oblivious except for a fascination with the automobile and its power (not itself applicable to Hopper, who only got as far as the gas station). Smith is successful precisely because he is not dragging the baggage of an alien European culture with him in the way that Caro, with the best will, cannot avoid in searching out the new. By contrast, what Pollock and Smith shared unwittingly was each artist's engagement in their vernacular roots combined with the rudiments of technology. To seek out the sublime in Smith, one needs to check out 'Hudson River Landscape' (1951), where a landscape is carved in the sky, replete with steel contouring. To a European eye, this is perhaps the great moment of the Tate Modern show.

Michael Spens