Lightroom, King’s Cross, London

22 February – 4 June 2023 (extended to 1 October 2023)

by JULIET RIX

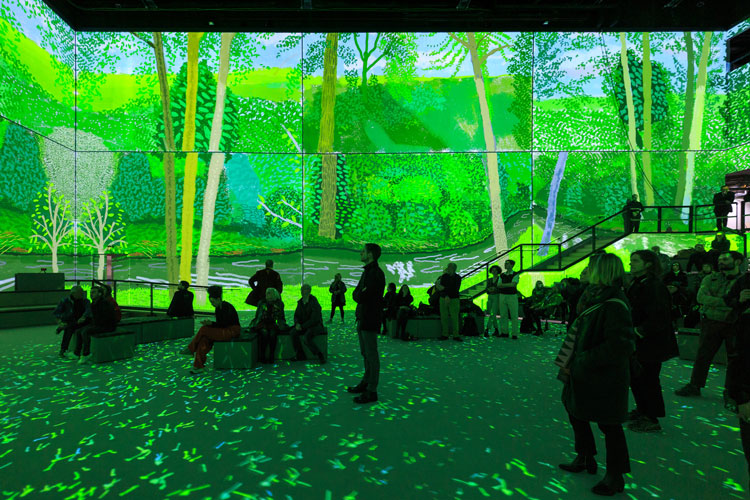

I am in Hockney’s woodland, looking along a path through the forest. Light dapples me and my surroundings. Trees in vivid colours rise all around. I can see every leaf, each blade of grass. This is the best of David Hockney: Bigger & Closer (Not Smaller and Further Away) – the immersion, the absorption of the viewer into the artist’s images, placing us within his works, inside his vision. It is most effective with the landscapes, of course, and the 270- to 360-degree giant screens lend themselves to images of roads and pathways. The Yorkshire Wolds – Hockney’s longtime home in the UK – and the woods around his present home in Normandy, unfurl on every side.

Some of the pictures were originally paintings, others were created on his iPad, stroke by stroke, layer by layer, and are now digitally painted once again on the vast Lightroom walls. We see the sun take form and rise, animated rain stripe grey across the scene. “There is no such thing as bad weather,” Hockney tells us. “I can look at the little puddles in the rain and get pleasure out of them … if it’s rainy I’ll draw the rain, if it’s sunny I’ll draw the sun … The world is very, very beautiful if you look at it, but most people don’t look very much.”

[image4]

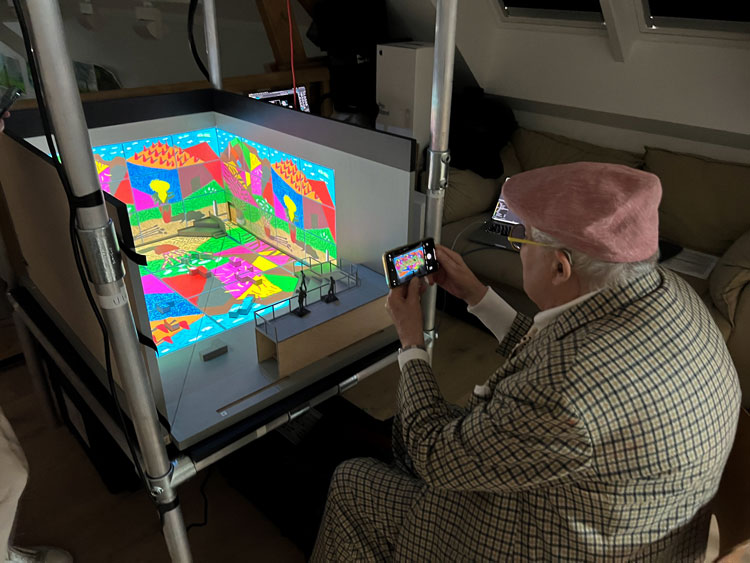

This show offers a chance to look, to see through Hockney’s eyes in a different way from a gallery. It is vast, easy, relaxed, almost effortless, and at its best (and it isn’t always at its best) simultaneously zeros in and broadens out our vision. Some have complained that this is not art. It isn’t exactly; it is more a way of appreciating art and the artist. It is incredibly accessible, but this is not imposed dumbing down; Hockney was involved throughout the show’s creation. He has always embraced new technologies and new media, and always made them his own. This time, as he says of designing opera sets, there has had to be collaboration, “and therefore compromise”. He can’t make this alone, but that hardly invalidates it.

[image5]

This collaboration is with 59 Productions (responsible for previous digital art experiences, including the National Gallery’s Leonardo: Experience a Masterpiece in 2021) and executive producer Nicholas Hytner, leading theatre director and founder of London’s newest large theatre, the Bridge (the architects of which, Haworth Tompkins, also designed Lightroom). The result is technically digital, but feels more traditionally cinematic – not quite virtual reality, more Imax-plus.

Crucially, the audience is in control of how they consume it. The vast room is open-plan. There are flat sofa-like seats dotted about, but most people stand around the edges or up on the balconies, or sit, or even lie, on the carpeted floor. How much you move about is up to you. When I was there, a trio of toddlers trundled about unimpeded, glorying in the shifting glow of the projected light, while adults mostly settled in one place, heads lifting and turning to take in the changing lightshow all around.

[image6]

In six loosely themed “chapters”, the display shifts between immersive installation and larger-than-life autobiographical documentary. The former makes more use of this new digital space, the latter feels not much more than expanded TV, but it’s still interesting. Hockney describes how he moved to Los Angeles in his 20s, finding a clarity in the California sun that he fell in love with, but at first “only straight lines” – until he moved to Beverly Hills. Here, the winding roads brought “squiggly lines” into his paintings – and on to the walls and floor now around us.

It is remarkable that even Hockney’s early LA paintings, traditional enough in their technique, lose nothing and often gain from the dramatic enlargement they receive in Lightroom. The clean lines of his people pictures expand effortlessly while his Hills-inspired landscapes are actively enhanced, the enlargement focusing the eye on the variety and complexity of the colours, lines, shapes and especially textures.

[image7]

In an early audiovisual work, Hockney takes us for a drive in his open-topped car, winding up California’s San Gabriel Mountains to a soundtrack of Wagner that crescendos to the peak. It is like an arty version of one of those pre-VR driving simulators (without the nauseating joggling around) and the music really does “match” (Hockney’s word) the landscape, highlighting the drama of the scenery.

[image13]

Music plays an important role throughout the show, with an evocative score composed by Nico Muhly (who has worked with Philip Glass, Björk and the Metropolitan Opera), as well as operatic accompaniment to the animated versions of Hockney’s many opera sets, a chapter that slots comfortably into this theatrical setting. A digital curtain swishes back and forth revealing a visual and musical medley, from childlike images of jumping frogs and flying bats from Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges (1980) to a surrealist Tristan and Isolde (1987). The opera chapter ends with what feels like a finale as the curtain sweeps closed on stirring strains of Turandot (1990), but it isn’t an ending. The show runs on a loop, a full cycle lasting just under an hour. You can stay as long as you like, and each viewer will find their own end point.

[image12]

As for Hockney, he may be in his 80s but this is no memorial. “My job is making pictures,” he says. “I’ve been doing it for 60 years … I’m still painting. And I’m still enjoying it enormously.” This artist is, hopefully, far from done, but happy to offer us a circling retrospective.

There is a chapter on “painting with a camera” – his collages of instant Polaroid photographs. These montages of images taken close together insert time into photography, he says, and like painting and drawing are created on the page not in the lens. Certainly, they allowed him to develop his own kind of cubism.

[image8]

Which brings us to another chapter, “lesson on perspective”. Parts of this we could have done without since they fail to exploit the spectacular Lightroom setting and feel more like a lecture. But Hockney’s take on perspective is certainly relevant. Traditional Brunelleschian perspective, he complains, sets the viewer up with just a single static viewpoint outside the scene. Hockney wants to give us perspective in motion, multiple views, to put the viewer – even in his 2D on-the-wall paintings – inside his image, to immerse us in it. Which makes this show seem a natural extrapolation.

[image2]

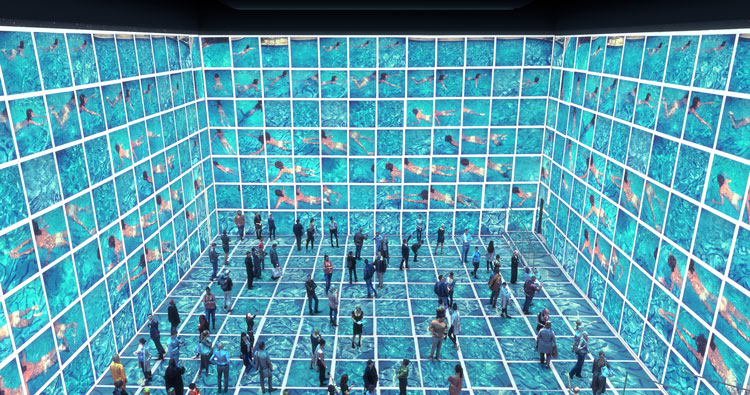

Which is why it needed a little less documentary and a little more immersion. Hockney’s pool pictures are, like his landscapes, a gift to an immersive lightshow. We find ourselves in Hockney’s swimming pools, his water curling across the carpet and rippling up the walls around us, but not for long enough. To look the way Hockney wants us to look, we need time, and the producers should trust that we won’t run off bored. Let us wallow in his vision a little longer. And bask, too, in his delight in life and the world around us. We need his optimism as this show opens under grey February skies, around the first anniversary of the Ukraine war, with our economy struggling. There is beauty all around us this show is saying, spring will come – a time, Hockney tells us, when “nature has an erection …[and] it looks as though champagne has been poured over the bushes and it’s all foaming up and it’s marvellous”.

“You can’t be bored of nature, can you?” he asks, “… if you really look. But you have to really look.” This show could have been even “bigger and closer”, but it does provide an opportunity to relax and let Hockney guide your looking, and there is some artistic enlightenment and certainly pleasure in that.

-.jpg)

-.jpg)

-.jpg)

-.jpg)

-.jpg)

.jpg)