Pace Gallery, New York City

5 September – 1 November 2014

by NATASHA KURCHANOVA

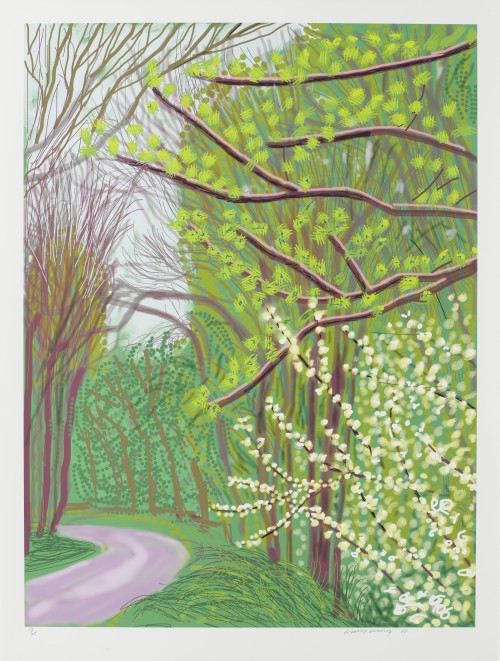

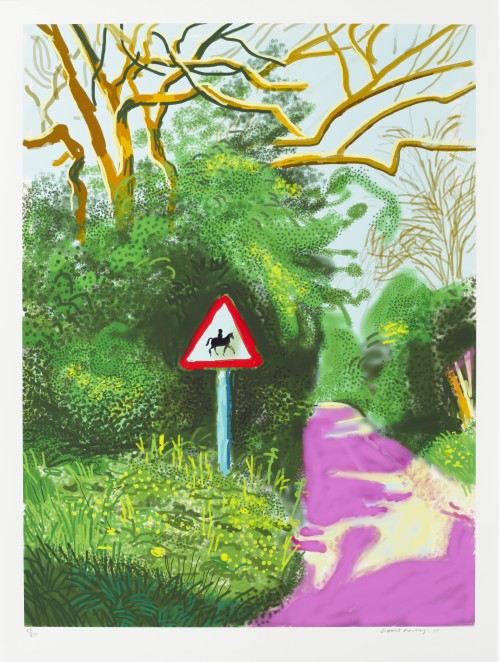

David Hockney is perhaps one of those rare artists who, like the Beatles, fits the majority of people’s tastes. At 77, he is one of the most popular living painters in the English-speaking world, having been painting and exhibiting since the early 1960s. He is still going strong, making pictures every day and showing them around the globe. How much of Hockney can we really have? What is the secret of his popularity? A series of recent drawings and prints on view at Pace Gallery in Chelsea offers a glimpse into the secret of his appeal. Trees, winding paths, leafy alleys – all rather idyllic scenes that are breathtaking in their ability not only to capture and convey the beauty of a particular corner of nature, but also, as with all good art, to open up for us the mind and heart of the artist himself. Hockney’s heart lies with the world – people he loves, places he visits. He has always shied away from abstraction and welcomed figuration. He has an amazing aptitude for memorising and using limitless devices coined by centuries of art-making, in the west and east alike. Despite being figurative, however, Hockney’s works are remarkable not for their subject matter, but for their formal complexity and invention.

The Arrival of Spring features drawings, prints and a video of English wooded lawns and leafy alleys done in Woldgate, East Yorkshire. Hockney grew up nearby and moved there from Los Angeles for a few years. There are 25 black-and-white charcoal drawings of woods near Woldgate. The artist dated them by the day: the earliest was done on 22 January and the latest on 27 May last year. Considering the difficulty of the medium – drawing with charcoal is challenging because it smudges at the lightest touch, and the scale has to be kept relatively small – the works are impressive for the clarity of execution and the finesse of detail. The artist divided them into the groups of five, by a specific location. Recording the slightest nuances of the changes in the season, including light, leafage, weather and time of day, these works showcase the range and extent of Hockney’s technical mastery, which is quite stunning, reminding us at once of Rembrandt and Matisse. The memory of Rembrandt is evoked by the technical finesse and the black-and-white colour scheme, while the influence of Matisse comes through in the carefully conceived composition, with its attention to the quality of light and the “framing” of the central space, which often appears empty, with batches of trees and shrubbery, as in the several landscapes the French master painted at Collioure, for example.

Hockney is a painters’ painter – he openly insists on the superiority of painting over photography in the truthfulness with which it renders the world.1 Photography, for him, is limited by a particular point of view and can always be manipulated, especially in the digital age. Interestingly, with all his love of nature, drawing and painting, and his dislike of photography as art, Hockney is an avowed technophile, who, in order to approach nature, uses a variety of mechanical devices of different degrees of complexity. For example, the photograph that accompanies his text in the exhibition’s catalogue shows him making a charcoal drawing of Woldgate from the passenger seat of his car. The work that appears to be done en plein air was actually done from inside a vehicle, which brought the artist to the woods. Considering Hockney’s devotion to what he does, his avoidance of direct “bodily” contact with nature is a definitive statement on the absolute uselessness of proprioception, motion and other biological senses that inform our vision. The bifocal optics is quite enough for the artist; he does not want to be in direct contact with nature, because he does not have use for invisible, sensual aspects of visuality that form part of our perception.

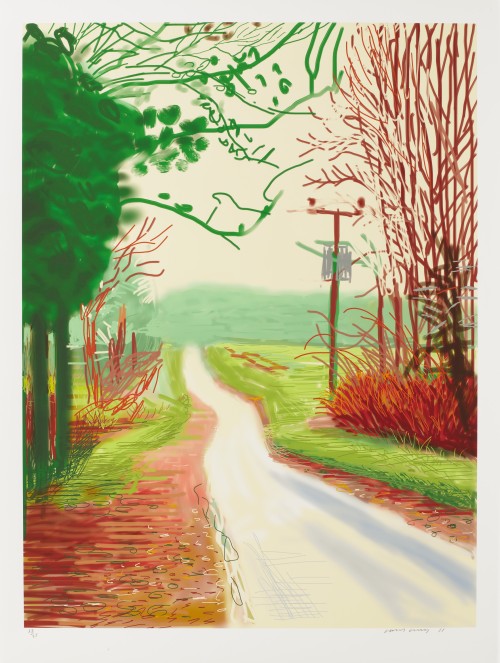

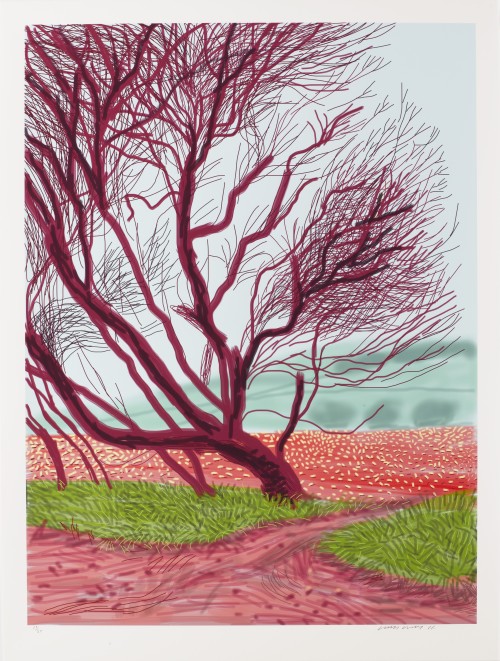

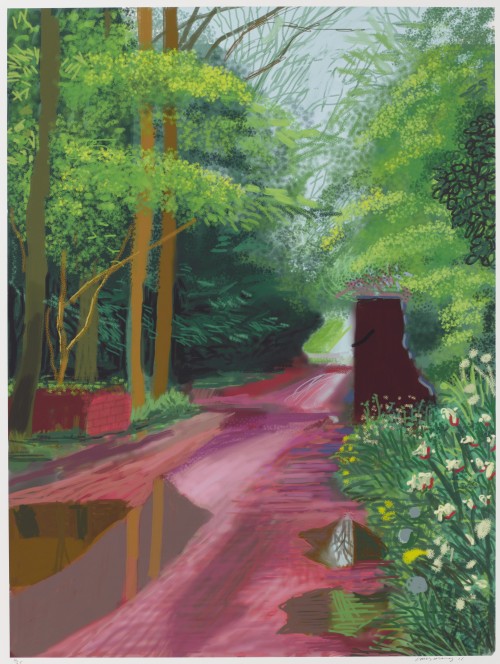

In the 80s, Hockney was using computers for painting; in the late 2000s, he tried iPhone applications for this purpose; more recently he switched to the iPad. Initially, a series of 13 large colour prints at the exhibition were also drawings done on an iPad. In his artist statement, Hockney said that he began using the iPad as a drawing tool as soon as it came on the market, in June 2010. From January to May of the following year, he was making the series The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty eleven), featured in the exhibition. From the beginning, he knew that these drawings would be used as the basis for much larger prints, so he varied the size of his strokes accordingly. The series is remarkable for its bold, iridescent colouration and an almost eerie luminosity, which seems to emanate from the surface of the prints. Apart from these distinctive features, conditioned by the technical device itself, the prints also convey the artist’s thorough knowledge of modern masters. The squiggly, nervous lines demarcating the branches, grass and road charge the surface with energy and dynamism worthy of the best canvases of Van Gogh and Munch.

Finally, to top off this display of technical mastery, knowledge and invention, Hockney included a video of the snowy landscape, which he filmed while driving, using multiple cameras attached to the sides of the car. The videos are displayed on identical plasma TV screens placed in a grid adjacent to one another, showing us all the pleasures we could have observed if we had nine eyes attached to a motorised device making its way through the snow in Woldgate Woods on 26 November 2010. The arrangement is spellbinding in the simultaneous slow unfolding of multiple, but similar views. The plasma screen allows for the light and luminosity of the image to manifest itself unhindered by a darkened room or the noise of a projector. The videos look like a visual dance, choreographed by an invisible master of ceremonies – in this case, obviously, the artist. The secret of Hockney’s popularity, then, lies in his tireless enjoyment of this world in his own particular way and in conveying this joy to anyone who looks at his pictures.

Reference

1. Disposable Cameras, Jonathan Jones interviews David Hockney, the Guardian, 4 March 2004.