Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh

24 July – 28 September 2019

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

In his book Chromophobia, published in 2000, David Batchelor explores the idea of the fear of colour in western culture or, more specifically, an association between colour and corruption, impurity and chaos. Explaining the orientalist, patriarchal and puritanical ideologies behind these fears, he discusses the ways in which, throughout western cultural history, colour has been associated with the colonised “other”, the “sinful” feminine, and has come to represent something to be sanitised or removed and, ultimately, to fear.

[image2]

The anthropologist Mary Douglas explored these ideas in a broader sense in her seminal 1966 work Purity and Danger. She wrote that the desire to purge society of “dirtiness”, usually using religious ideas as justification, is a ritualistic behaviour that is deeply ingrained in our society and is used to order and control groups of people. The central point to this controlling behaviour, of course, is the elevation of certain ideas of “purity”, “holiness’, and, as Batchelor focuses on in this exhibition, “whiteness”. This underlying obsession with “whiteness” is not merely aesthetic, but a broad-ranging social, cultural and political point of contention.

[image10]

In this context, My Own Private Bauhaus, at the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh, is a defiant act. As he makes the case for colour in his excellent, beautifully written book, Batchelor also makes it here. Using the legacy of the Bauhaus movement as a springboard – this year marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus by Walter Gropius – he explores colour through sculpture, installation and painting. In so doing, he pays tribute to that innovative movement, as well as expanding his lifelong project to celebrate colour and thus to undermine the western obsession with whiteness.

[image8]

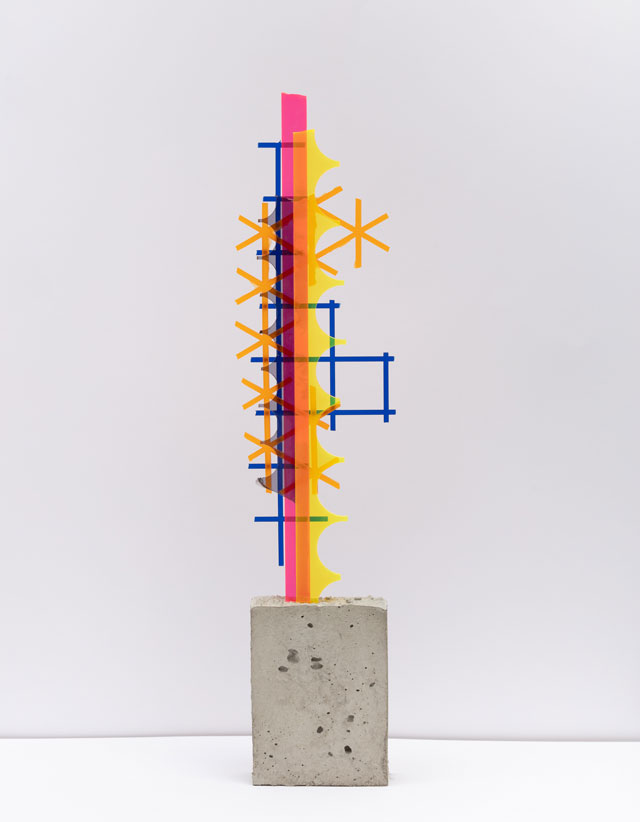

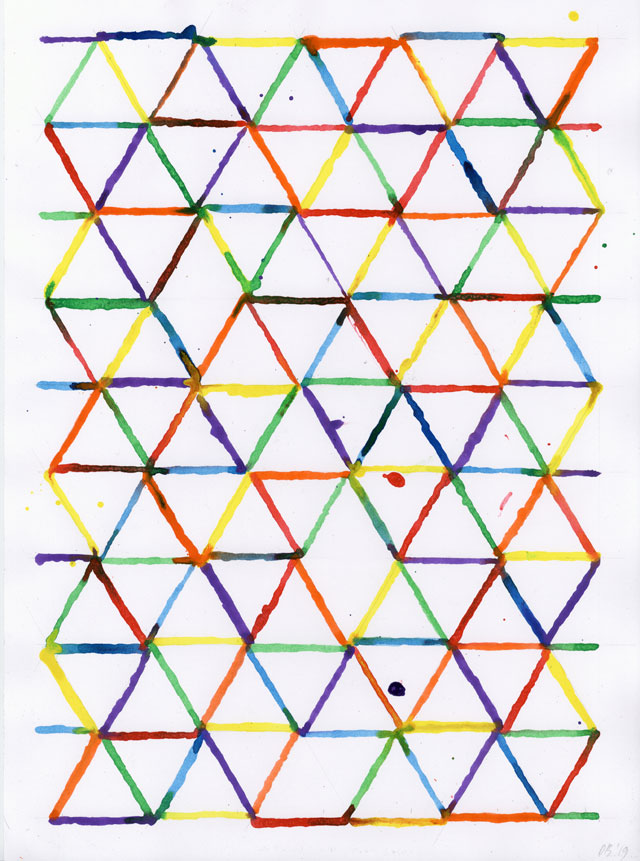

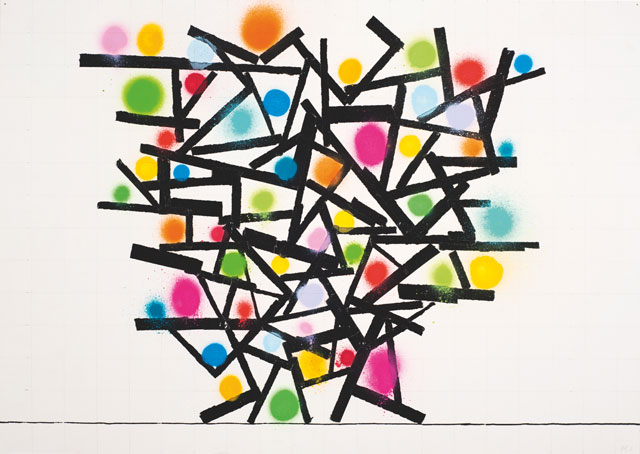

Indeed, while the works in the show do recollect the shapes and colours of the original Bauhaus movement, they also play with its sense of order and, in a way, subvert it. While the Bauhaus favoured symmetry and clean, geometrical shapes, Batchelor’s works are, in the artist’s words, “often damaged, bent or broken; and the colours, while vivid, are neither pure nor primary”. Batchelor is more interested in forms that do not quite follow the rules, that are imperfect in some way. Just as colour is a way of rebelling against the politically loaded idea of whiteness, Batchelor also subtly subverts the Bauhaus movement’s obsession with precision, symmetry and the idea of an aesthetic code itself. As he admits, he has “a distrust of formal ordering systems and regulated theories of colour”.

[image9]

The materials used, too, are irregular, often discarded, rather than purpose-built or ordered, so there is a sense of chance and an underlying feeling of repurposed chaos in the exhibition. Using plastic offcuts, shards of glass, found objects, metal mesh, tin tops, timber, concrete, gloss paint, spray paint and adhesive tape – materials thought of as unwanted, or easily discarded – he fashions them into cohesive artworks in an exhibition that quietly undermines every assumption of what it is to be of value in contemporary art.

[image3]

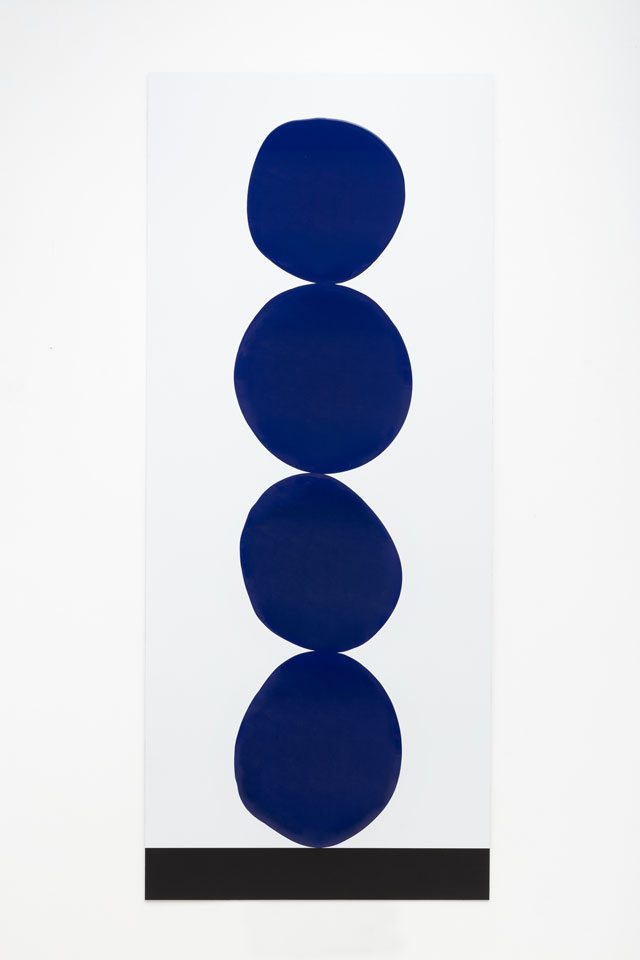

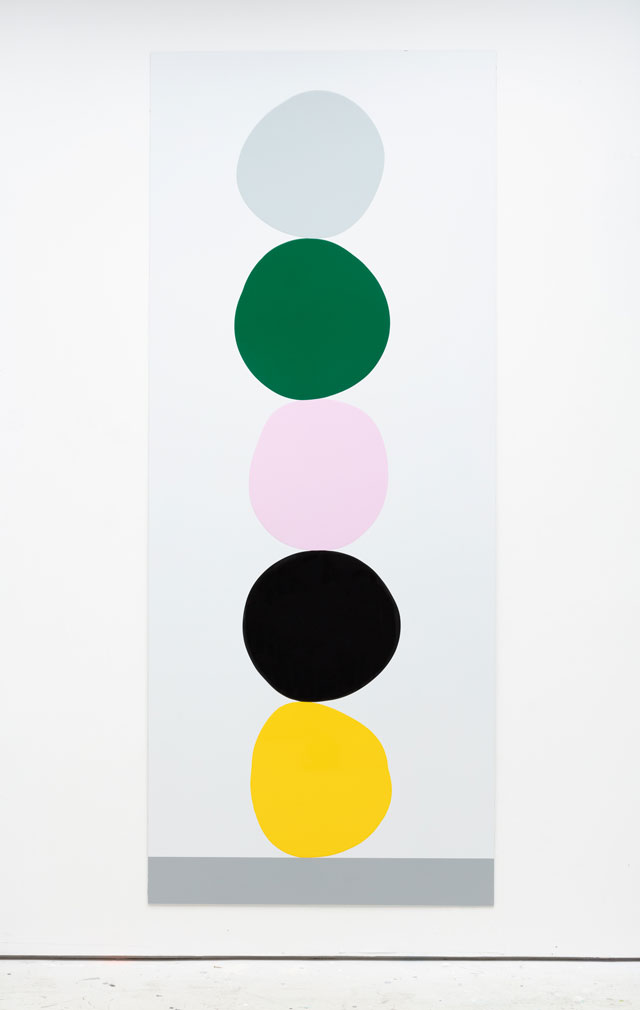

And while, at first sight, the layout of the exhibition gives the impression of order and cleanliness, the shelves on which these sculptures are displayed are irregular and slightly off kilter; careful chaos is woven into every level. In his Colour Chart paintings, made using commercial paint poured on to aluminium panels, off-circular forms balance on plinth-like bases, giving a sense of instability and precariousness. Yet they hold together, they function. Despite their formal imperfection, there is nothing wrong with them.

[image5]

Ultimately, Batchelor’s exhibition is an excellently executed statement of his ideas about hierarchical values in modern art and in western society at large. It shows one can be serious and genuinely subversive at the same time as being playful, irreverent and fun: intellectual substance does not require the need to be overwhelmingly heavy and pessimistic. In flouting aesthetic and political authority in a subtle and personal way, in embracing idiosyncrasy, Batchelor injects serious and timely issues with much-needed optimism and originality. He refuses to disappear into monochrome or adhere to age-old aesthetic rules and assumptions about materials, order and purity.

[image6]

So, although Batchelor pays homage to the Bauhaus movement, he aligns more closely with his predecessor, the Edinburgh artist Eduardo Paolozzi, who brought life and vibrancy to the postwar era, or to the contemporary Glasgow artist France-Lise McGurn, whose use of colour in her figurative paintings and installations also flouts the heaviness and quiet hierarchies of current Scottish art. In these negative and regressive times, it is a relief to see that some artists persist in these quiet, colourful and optimistic rebellions.

.jpg)

.jpg)