Camden Arts Centre, London

2 July – 17 September 2017

by CELIA WHITE

Daniel Richter’s Lonely Old Slogans is a small show with a big voice. A mere three rooms chart the German painter’s career since the 1990s from abstraction to figuration and back to abstraction again, yet nothing about the style or substance of these paintings is clearcut. Richter himself rejects the distinction between figuration and abstraction, noting only a difference in how we decipher their respective forms. On the back of this radical view, his latest show at Camden Arts Centre conjures a fantastical realism, a proliferation of voices, effects, languages and cliches through his bold, bright canvases.

[image10]

While their subjects are not always recognisable, Richter’s scenes incorporate real events and their representation in the news media, as well as dreamed-up scenarios presented as theatrical constructions. His paintings’ continual slipping between these modes demands sustained attention from each viewer of each canvas, making it difficult to hang them together in a coherent narrative or group. Study on the Amazing Comeback of Dr Freud (2005), for instance, shows a naked, turbaned man in high heels standing vulnerable against a wall in a forest setting, its title suggesting at once a specific event, a romanticised account and the vagaries of the unconscious that were Freud’s object of study. A similar confusion inhabits Ferbenlaare (2005), in which a prostrate, corpse-like male figure dressed in a dreary harlequin pattern stares up through a tight grid of brightly coloured squares. Richter somehow combines a formal experiment in tone, hue and saturation with the suggestion of a dark scenario not quite explained or realised, like a Renaissance altarpiece’s deathly predella.

[image7]

In this way Richter’s canvases liberate in their openness to interpretation. Undercurrents of violence, isolation, awkwardness and oppression abound, while absurdity, surrealism, confusion and the pure attractiveness of colours and shapes lend the works a ludic quality. Is the red apparition in 1937, Legitimate Criticism (2005) a nightmarish flayed form or a ghost simply crossing the threshold – represented by black and white painted frames receding into the canvas – between gallery space and pictorial space? “In my paintings you always see something which isn’t there,” Richter has stated – and this is true, despite the fact that so much is supplied.1

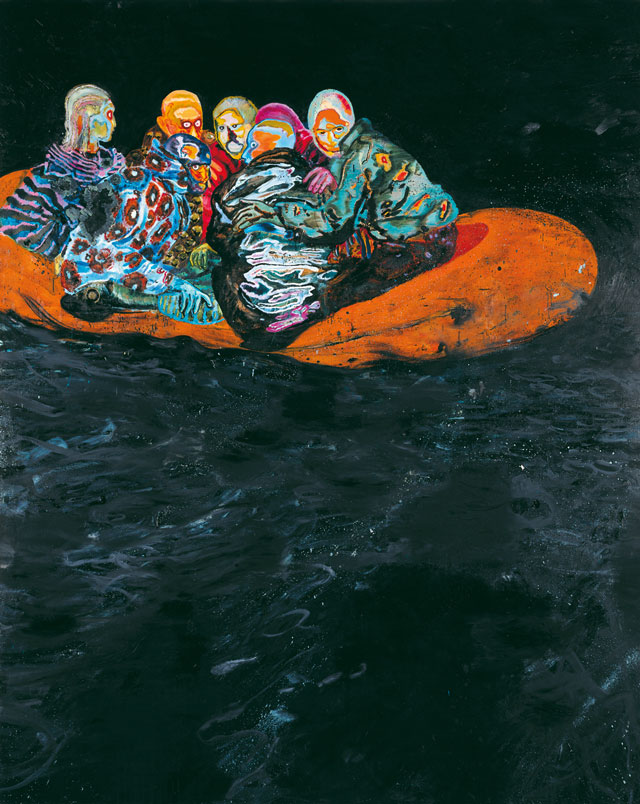

Like the work of prewar German expressionists whose work influenced Richter, such as Max Beckmann and George Grosz, several of his scenes carry a political message. Tuanus (2000) has the scale of a history painting, the painterly gestures, blobs, patches and scrapes of impressionism, expressionism and American abstract expressionism and the graphic effects of screenprinting and technicolour – a sumptuous surface that belies the work’s apparent subject: a drugs raid in central Frankfurt. The filmic incandescence of this work contrasts with the eponymous Lonely Old Slogan (2006) that hangs nearby, while its message is equally strong. In this black and white, dripping painting, the slogan “Fuck the police” is seen through the eye of a tunnel pasted on to the back of a man’s leather jacket. Here the silence of the saying, holed up in this desolate urban nook, indicates the emptying out of its meaning: a lone, individual plea that is no match for the weight and power of the governments and institutions it seeks to upend.

[image2]

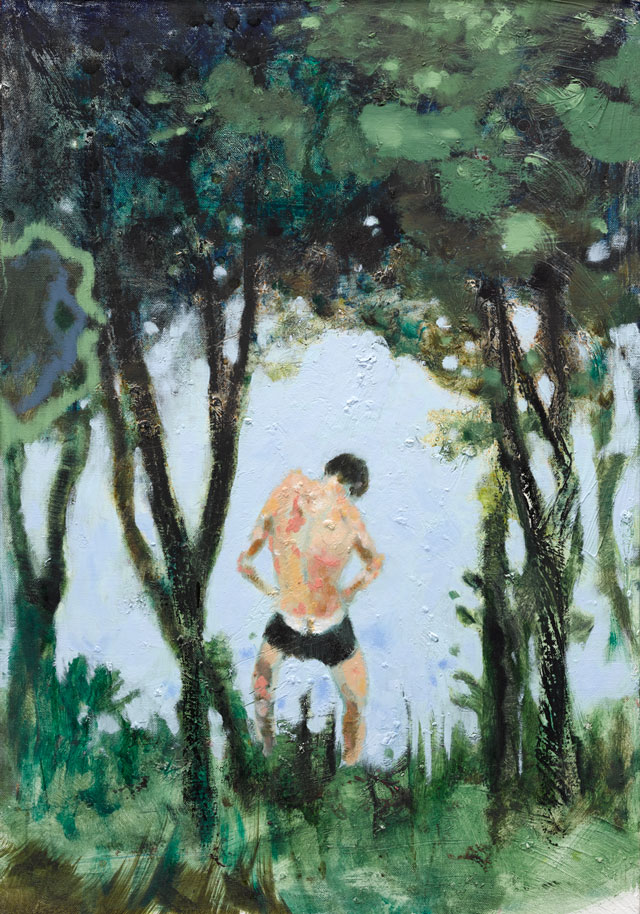

Richter’s viewers bear witness to such utterances; are cast as voyeur; are implicated as they watch. We stare from behind at a man masturbating in a forest in Half Nude (2013) and observe a scene of possible debauchery and definite violence in Amsterdam (2001). In a series of small paintings from 2009 showing country borders, barriers and watchtowers, we confront our own voyeurism through its transferral on to the surveillance of individuals by organisations and systems, making the watcher feel watched.

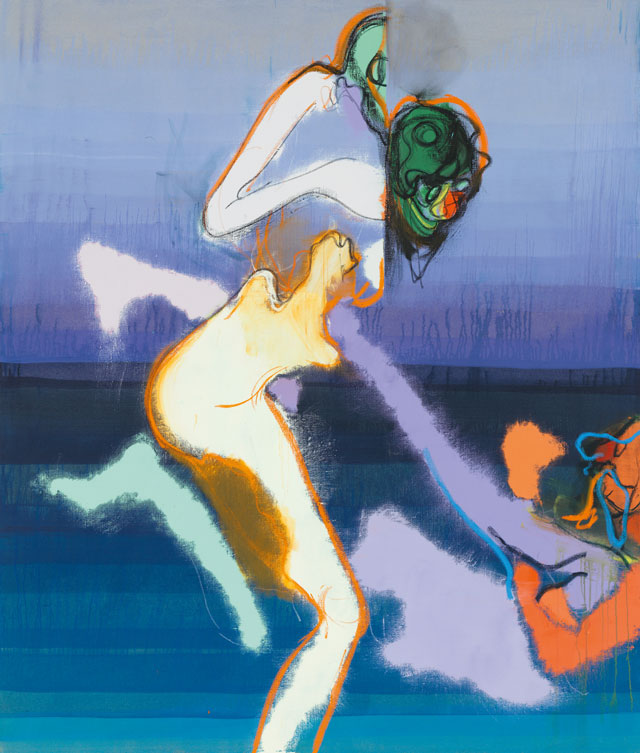

With the shift to Richter’s more recent phase of abstraction in the third room of the exhibition, formal experimentation mixes with playfulness again in the clownish, creepy deformation of Francis, the Cheerful (2015), while Will the Red Beat the Black? (2015) stages a colour war in which a political subject is expressed in the contours and conditions of the paint. Meanwhile, the sinister faces and distorted bodies of Asger, Bill and Mark (2015), likely referencing the expressionist painters Asger Jorn, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko and based on internet pornography, coincide in a threatening counter-historical tableau in which swathes of paint seem to render the three angrily opposed yet sexually inextricable.

[image8]

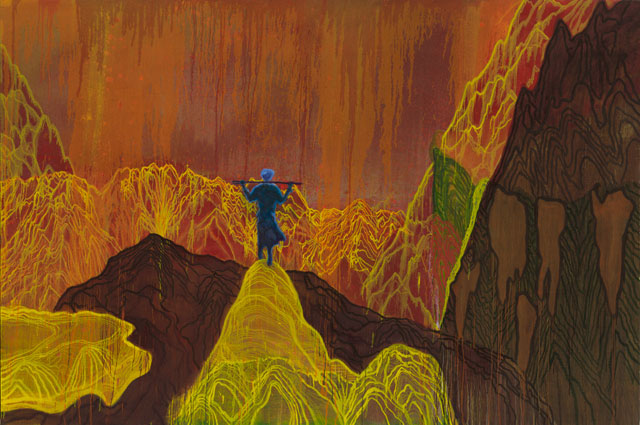

Richter impresses in his ability to present near-familiar, almost-relatable scenarios and encounters that demand attention yet remain detached, introverted, burdened by violence and melancholy. What we take for a form of voyeurism – life seen covertly, from a distance – is in fact Richter’s way of highlighting humans’ predisposition towards loneliness and emotional starvation, and their need to infuse what they see with narratives, ideas and feelings. The loneliest painting in the exhibition is A Flower in Flames (2012), in which a tiny figure is seen from behind in a hot orange landscape, quoting and inverting the sublime power of Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. Yet Richter drains the romance of Friedrich’s “alone” and replaces it with the emptiness of “lonely”. His work forces viewers to confront their own process of creating meaning and message in a world in which they live, ultimately and necessarily, in isolation.

Reference

1. Daniel Richter in conversation with Poul Erik Tøjner. In: Daniel Richter: Lonely Old Slogans, Humlebæk: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Vienna: Belvedere/21er Haus, Vienna, and London: Camden Arts Centre, 2016, page 75.