by JANET McKENZIE

Songlines XXX – Adnyamathanha Yarta at Rebecca Hossack marks 30 years since the establishment of the London gallery, during which time Hossack has almost single-handedly introduced Australian Aboriginal art to Britain and Europe. The gallery’s annual Songlines seasons have introduced many leading Aboriginal artists to an international audience. To mark her 30th-anniversary celebration, Hossack has chosen, not a blockbuster show of established artists, but the first solo exhibition of 34-year-old Damien Coulthard from South Australia.

[image3]

Coulthard’s suite of paintings tells the creation stories of the Flinders Ranges in South Australia, a place of immense significance to his Adnyamathanha people, relating to sacred, social and environmental history. For Aborigines, every event leaves a record in the land. Understanding the creation stories and the sacredness of particular sites has empowered Australia’s first people to assert their land rights. Coulthard’s paintings evoke Songlines – the travels of indigenous people across the vast land for millennia, through many different language groupings. Aboriginal culture is an aural culture kept alive through ceremony and ritual. Songs and dances performed during the epic travels have been performed at large gatherings.

[image9]

Coulthard created his paintings using ochres from sacred sites in the Flinders Ranges, which he applied direct to the canvas or on to an acrylic ground. Ochre symbolises the land, and the method of application evokes the layers of mystery and meaning associated with his people’s connection to it. Ochres were traditionally used to adorn the human body during ceremonies. The red ochre employed by Coulthard is one of the main pigments used in rock art: thus, his work is embodied within the ancient culture of his forebears. Red ochre is one of the most important minerals in Aboriginal mythology. In the case of the Bookartoo (or Parachilna) mine in the northern Flinders Range, it was said to be the blood of a sacred emu. Only initiated members of the Adnyamathanha people are permitted to use ochre from the Bookartoo pit so Coulthard, in fact, gathered ochre from a nearby site. By using ochre from the Flinders Ranges, he is asserting his direct ancestral connection to his people and to the land.

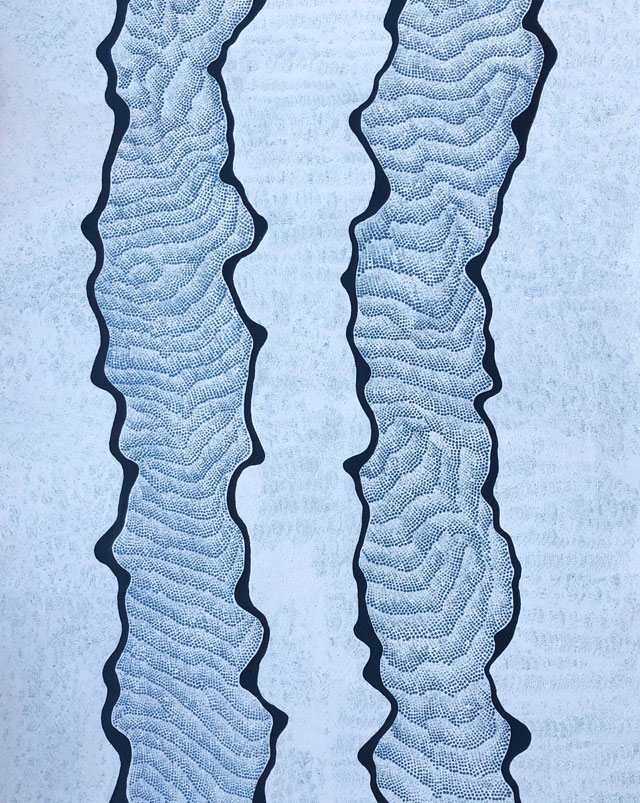

According to the Adnyamathanha people, the Flinders Ranges, with Wilpena Pound as its iconic central feature, was formed by a sequence of episodes involving travelling serpents (Akurra). Coulthard tells these stories in works such as Ikara Wilpena Pound (2018); Travelling Serpents: The Gammon Ranges and Flinders Ranges (2018) and Akurra in the Night Sky (2018). When he talks about his paintings, the artist explains that the Dreamtime also laid down the patterns of life for the Aboriginal people. It establishes the structures of society, rules for social behaviour such as marriage, and the ceremonies performed to ensure continuity of life and land. As a schoolteacher and artist, Coulthard seeks to empower young Aborigines to find a better path in life. The works in the exhibition were all painted this year.

[image4]

Janet McKenzie: How did you come to choose a career as an artist and as a teacher?

Damien Coulthard: My first career is as a teacher and I have always loved working with youth. Once I finished school, I moved to Adelaide, then university and in to the teaching system. I was lucky to have a number of role models in my life: grandparents, aunties and uncles, my mum and dad. A lot of young Aboriginal people do not have good role models and I really wanted to provide that as a teacher to them. Working in education and helping them to make better decisions and to understand their culture is very important. My role as a teacher can also help to close the gap between white people in Australia and Aboriginal people.

JMcK: Which school are you teaching at now?

DC: I’m at Le Fevre High school in Adelaide, which has close to 400 students with a big Aboriginal population within it. We have students who represent a range of Aboriginal groups within South Australia and we also have students coming from the Northern Territory and Queensland. There are a number of places, including the South Australian Aboriginal Sports Training Academy, that provide support for young Aborigines and that programme has been developed to help Year 11 and 12 students, in particular, to excel in whatever area they choose. Initially, football and netball were considered to be the most effective tools of engagement, but support is now extending into a more holistic engagement with education. That is what I think is important in working with Aboriginal people so the programme is developed in a respectful way that meets their needs.

JMcK: What would your pupils think if they saw your exhibition here in London?

DC: I keep my art quite private, although I have shown two or three students my artwork, in order to show them an alternative path to sport. A lot of our students aspire to play for the Australian Football League, but they need a backup plan. I try to help them develop multiple interests.

[image6]

JMcK: There is an ephemeral quality in your paintings; the forms are seemingly in constant motion. Can you explain why the painting that is made up of predominantly lavender and blue looks so different from the other works here in the exhibition?

DC: Ikara Wilpena Pound (2018) was the first painting I made earlier this year. It is dedicated to the sacred place Ikara, now known as Wilpena Pound, where the first ceremony of my people, the Adnyamathanha was held. Wilpena Pound in my people’s dreaming is where everything started; it is a vast place in the landscape in South Australia that resembles a giant amphitheatre and here I have painted an image of that very first ceremony. Wilpena Pound is a magical place and it possesses great energy. I really wanted those aspects of the place to come across. In the history of my people, the edges of the dramatic steep walls are actually the bodies of two intertwined Akurra (giant serpents or snakes) whose journey from the northern Flinders Ranges changed the landscape dramatically. The Adnyamathanha people were about to hold a huge ceremony. As an artist, I am imagining the group that is about to celebrate and share their culture through stages of initiation. The circles in this work refer to acquiring knowledge and eventually being able to transition out into the world. I want to convey to the viewer the cultural and spiritual essence of this magical spot.

[image8]

JMcK: Can you describe the pair of paintings here: Urdlu the Red Kangaroo and Mandyu the Euro, and Lake Frome (both 2018)?

DC: The first of this pair of paintings tells the story of the red kangaroo and the grey kangaroo. It is a story that is taught to young children about being respectful of each other and of each other’s environment. It’s about food: Urdlu, the red kangaroo, did not share his food with Mandyu and when Mandyu found out, he was really upset. The story is also about the importance of tracking, of being able to track food across country. Mandyu tracked Urdlu to his hole where he was hiding his food and they ended up having a fight. The fight caused the red kangaroo to become a big strong creature with long arms and long legs and the grey kangaroo to become very short, stocky and grubby, which is why he was forced to live up in the hills thereafter. The creation story tells us how the rocky Flinders Ranges were formed and then separated from the adjacent plains by a magnificent sweep of Urdlu’s tail; how Lake Frome (Munda) came into being as a salt lake and where the pointed hills (Thunupinha) came from.

[image10]

JMcK: Akurra at Lake Frome is delicate and rhythmic.

DC: The Akurra giant serpent is a scary character with a beard and fangs. He is the guardian of water holes and travelled down to Lake Frome (not knowing it was a salt lake). This is Akurra lying across the lake after drinking from it and then spewing it all out. Aboriginal people associate this area with bad spirits, and later it was where uranium was discovered and mined. Ironically, the mines have now helped the struggle for Native title because the money had to be paid by the mining companies to the Aborigines, and the money from that has enabled the acquisition of Wilpena Pound, which is now a major tourist development.

JMcK: You are teaching white Australians what the land means to your people.

DC: My great-grandmother, Annie Coulthard, worked in education. In the last 10 years of her life, she recorded her stories. She was one of the last people to be able to record them using our language, both in our language and in English. It was published in 1988 as a book, Flinders Ranges Dreaming, and it was the first record of our people’s stories. She was one of the last to have a deep understanding of our culture and of our ancestral beings. Her knowledge of Adnyamathanha culture has since been passed down to me, by my grandparents and by my aunties and uncles. In January this year, I was lucky enough to go to the Flinders Ranges with my parents and with my Uncle Noel and Auntie Sandra. We walked around the country and we visited one of the main three ochre pits in the area.

[image7]

JMcK: How is the ochre dug from the pit and how is it prepared for painting? And what is the significance of working with the material dug from sacred sites?

DC: The ochre is embedded in the earth. The ochre in Bookartoo is very fine. When you dig it out and crumble it, it is almost like the texture of flour, silky smooth. Our main ochre pit at Bookartoo (the Parachilna mine) is near Wilpena Pound, 429km north of Adelaide, in the heart of the north Flinders Ranges. It was a sacred ochre pit and if you are not a fully initiated man, you cannot enter that area. If you are not a custodian of that land, you cannot enter it either.

Aboriginal Australians have been using the ochres from this area for more than 60,000 years. In 2016, a site was found in the Flinders Ranges that has been dated as 49,000 years old. Artefacts have been documented and published, including bones that were used as tools, and bones of megafauna. The lines of travel and the trade routes across the country were marked by song on the journey to Bookartoo.

[image5]

JMcK: Can you explain this, a predominantly black painting: Yurlu the Kingfisher – One of the Leaders of the (Malkada) Ceremony (2018)?

DC: Yurlu started out from Karkalpunha to go south to Ikara (Wilpena Pound), which is the ceremonial ground of the Vardnapas (the first stage of initiated men). On his way, he stopped and made a fire that sent up a huge volume of smoke. This was a sign to those who were waiting at Ikara that he was on his way to the ceremony. The fire left coals within the earth and that coal has since been mined out of the earth today. Yurlu’s coal at Leigh Creek has therefore supplied power to South Australia from 1940 to 2015. The colour in this mostly black painting represents new life because when you go to Leigh Creek today, you can see the remains of the coalmines on the black hills, but it is in the process of revegetation so, hopefully, in say two years’ time, it will look a lot better.

JMcK: Can you describe what you are seeking to achieve for yourself and your people through your painting?

DC: My main inspiration is to strengthen my own identity. As a teacher, I try to enable my students to take pride in their culture because, in turn, that will enable them to do whatever they choose to do in the future. My grandfather was a great role model and so was my nana, yet, at the time, I did not really know the extent to which they were helping me. Their influence has instilled meaning into different locations that they took me to. To be connected to country you have to go out into it, to feel it in order to be able to understand it. In the Flinders Ranges, I get this longing, this power within; it is really exciting when you feel a connection with ancestral lands like this. My great grandmother’s book is used in the education system. There are language classes available now, and her book is used as a source. A lot of Aboriginal culture and language is aural, so it can be lost if it is not recorded for future generations.

JMcK: How did you learn to paint like this?

DC: It’s an extremely hard question to answer. With all my painting, I draw from visiting the location and where I try to make a connection. I take a visual image, I read the story that has been given or passed down by my grandfather or other family members, or from my great-grandmother’s book, and then put it on to the canvas. I don’t like to sketch it out or overthink it too much. I create a visual image in my head and then go for it.

• Damien Coulthard’s work is on show as part of Songlines XXX: Adnyamathanha Yarta at the Rebecca Hossack Gallery, London, until 24 November 2018.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)