Gagosian Gallery, London

11 February–1 April, 2010

by DAVID BRITTAIN

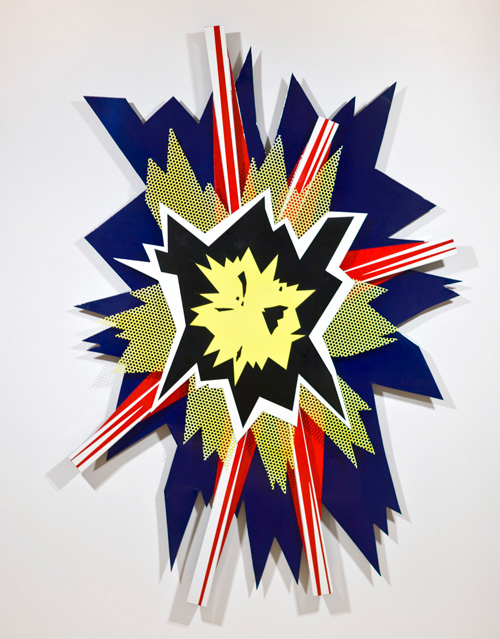

One aim of CRASH – named after one of Ballard’s most notorious books – is to explore correspondences between the influential author and the artists he admired, such as Bacon, Bellmer, Delvaux, Dali, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Ruscha and Paolozzi, who are all represented here. Another aim is to speculate about the manner in which the writer may have influenced more recent artists. Interestingly, the way the organisers approached their task corresponds to Ballard’s advice to artists to abandon “adding fictions” to the world and instead to scour the image world for evidence of the logic of the media landscape. Though here the search was confined solely to the world of art images and the logic under scrutiny was Ballard’s.

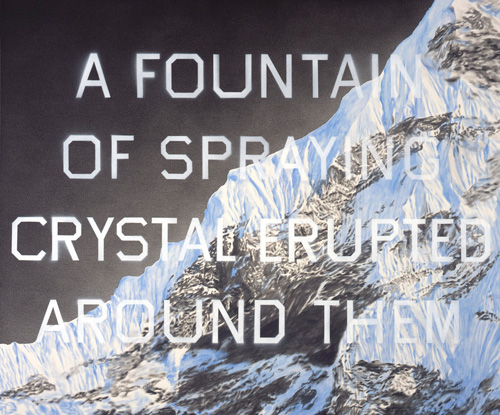

More than 170 excellent individual works in many mediums have been selected to convey “Ballardian” concerns. Science is represented by grisly contributions from Damien Hirst and Paul McCarthy and a video projection, shot at a former Soviet rocket site, by Jane and Louise Wilson; pictures by Helmut Newton and John Hilliard and Jemima Stelhi’s surprisingly erotic studio collaborations evoke sexual perversion. Ballard’s recurring symbol, the car, is provocatively manifested by Richard Prince’s totemic Elvis (2007), the carcass of a dream car mounted on a plinth. Another memorable car-themed work comprises two snapshots of floral tributes to the dead Princess Diana from Jeremy Deller’s Another Country (the Mall 3/9/97) (2009). Jeff Koons’s altered porno shot, Couple (Dots) Landscape (2009) emblematizes Ballard’s notion of the “death of affect”, the emotional numbing caused by over-exposure to mediated imagery. Ballard’s theme of entropy is invoked by the amazing Untitled (2009) by Roger Hiorns, a hanging engine block sprouting blue crystals; and cleverly there’s a photograph by Tacita Dean that Ballard himself wrote about in relation to Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970). Meanwhile, notions of inner space proliferate across a range of works by Edward Hopper and Dan Holdsworth (his twin photographs of an uncanny night highway) and by Mike Nelson whose walk-in structure, Preface to the 2004 Edition (Triple Bluff Canyon) (2004), resembles the foyer of some Lynchian movie house. Arguably all of Ballard’s obsessions could be encountered in Paolozzi’s 1970 print edition, GENERAL DYNAMIC F.U.N. that is installed conveniently close to McEwen’s trashed wheel assembly.

This ambitious and intelligent exhibition could almost certainly not have been staged by a publicly supported gallery due to much provocative content (it included, for instance, “paedophiliac” images by Bellmer). A big omission from the list of Ballard’s obsessions was film (though Douglas Gordon’s tarnished publicity images of starlets to some degree stand in for cinema) and the popular and scientific imagery that flavours so much prose.

One of the show’s contributions, in my view, is to identify or hint at little known aspects of the Ballardian that can shed light on the writer’s well documented interest in art. Ballard is quoted in the excellent catalogue (decorated by copies of insurance photos that he took of his crashed Zephyr in the 70s) as saying that he always wanted to be an artist but never had “the talent”. Yet, as his readers will know, Ballard “realised” alternative versions of images and works of art via his prose. For instance The Atrocity Exhibition (1970) attributes a work (mistitled Dodge 38) to Kienholtz that differs in substance from the one we know from countless reproductions.

For CRASH Jake and Dinos Chapman provided a commentary on this practice with their multiple Bang, Wallop, a pastiche of a lurid paperback. Attributable to one JD Ballard, the prose is an affectionate take-off of Ballard’s style that progressively degrades under the influence of “crashing” software.

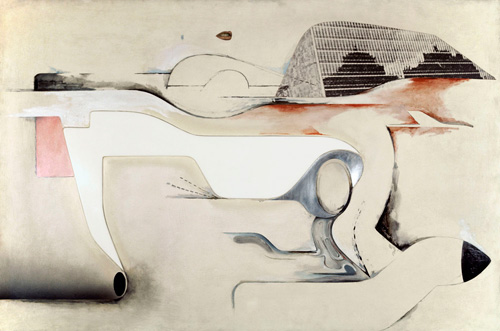

Artists taught Ballard that the image could be possessed in so many ways. Surrealist art for instance transformed the familiar into the strange, and pop artists revealed the dark libidinous content of everyday things. This exhibition, then, is a fitting tribute to one of the most visual of all British authors and to some of the artists he admired.