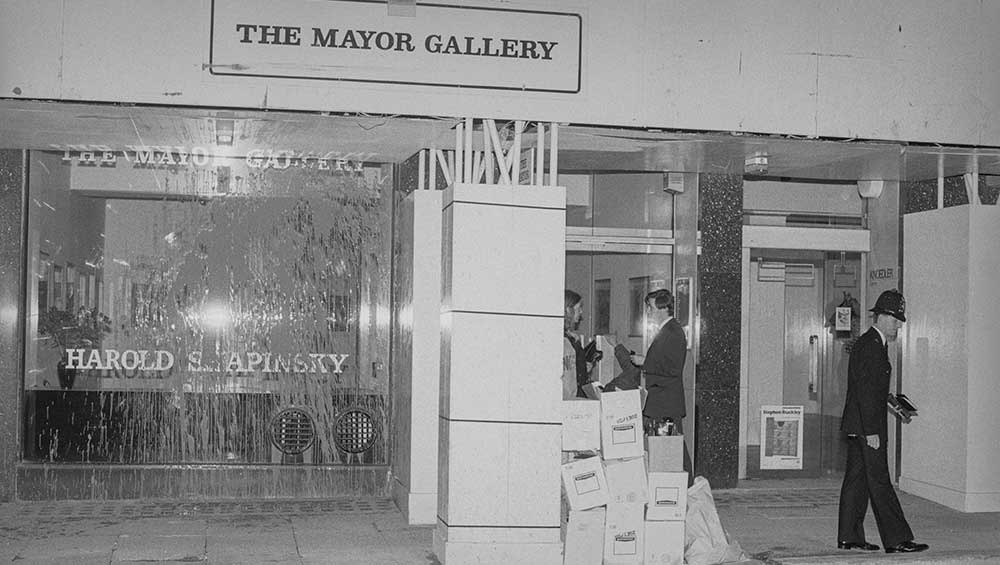

The Mayor Gallery, London

12 January – 25 February 2022

by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

On 21 May 1985, writing an almost real-time account of the Grey Organisation’s assault on Cork Street, in London’s Mayfair, the group’s de facto leader, Toby Mott, exulted in their commitment to see the thing through: “We are not like the other tossers talking about this and that, we are going to do it.”

Setting off in a Ford Transit van from the bohemian French House in Soho, Mott and members of his rebel army pulled grey overalls over their cold war grey suits as they headed for the inner sanctum of London’s art establishment, Cork Street. Lookouts were already in place and at the agreed signal of flashing bicycle lights, the Grey Organisation (GO) began systematically flinging grey paint (generously diluted to ensure a long range of splash) over the length and breadth of the street’s galleries. The action was completed in less than a minute before the group made a proverbial quick getaway, speeding off to Zanzibar, another modish watering hole, this time in Covent Garden.

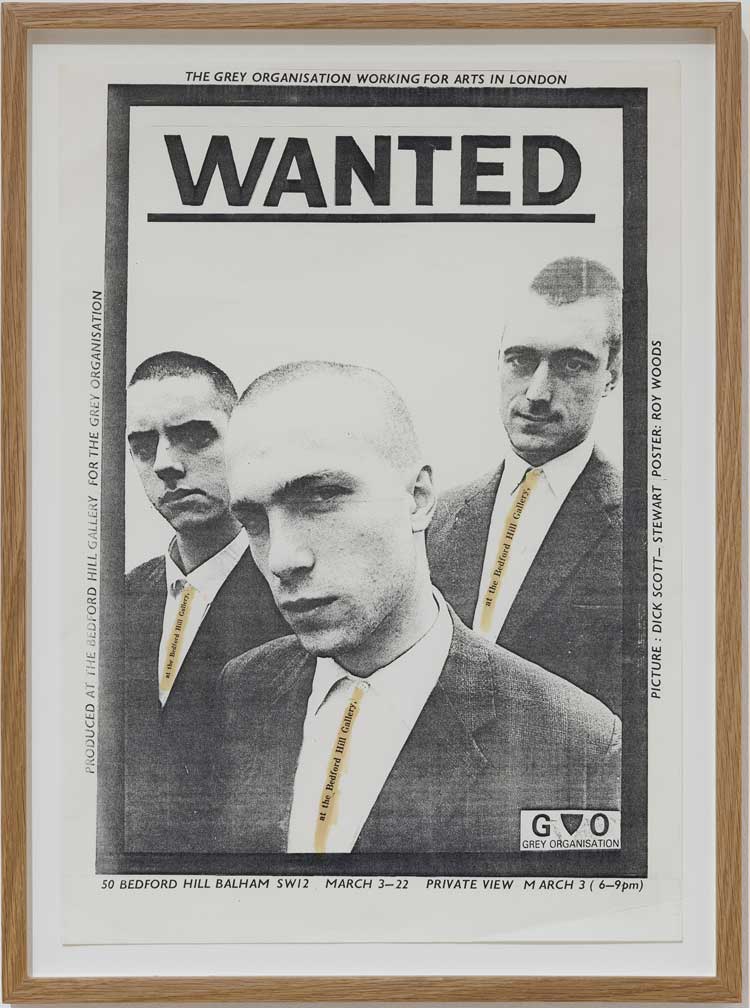

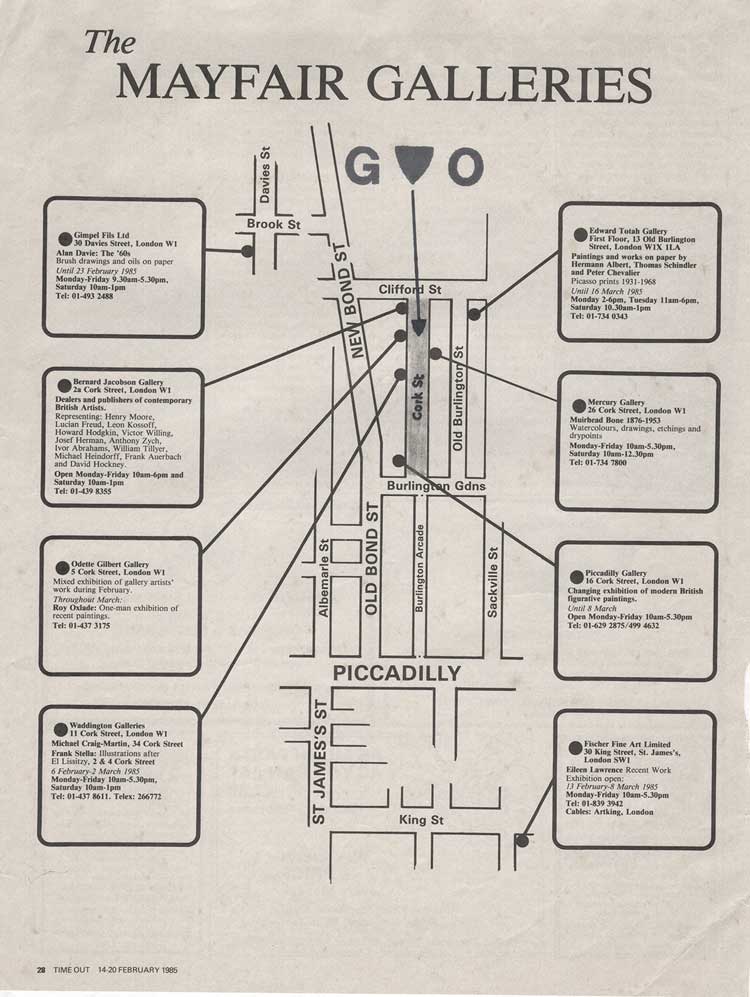

[image2]

Officers were dispatched to the scene of the crime from the nearby West End Central police station on Savile Row – incidentally, the same constabulary that had put a killjoy stop to the Beatles’ rooftop concert 16 years earlier.

Two days later, they were arrested at their digs in Bow, east London, unsurprisingly given that they had publicised their incursion with a press release and handy map. The group was subsequently banned from central London, a rather hawkish prohibition that has been attributed to the presence of an MI5 seat on Cork Street.

[image16]

In a laconic mission statement for the Cork Street “terrorist” attack, as they bombastically termed it, the GO summed up the raison d’être of their assault which: “should not be interpreted as vandalism” but as a comment on “the boring and lifeless art establishment. We intend to liven up their lives a little.”

[image15]

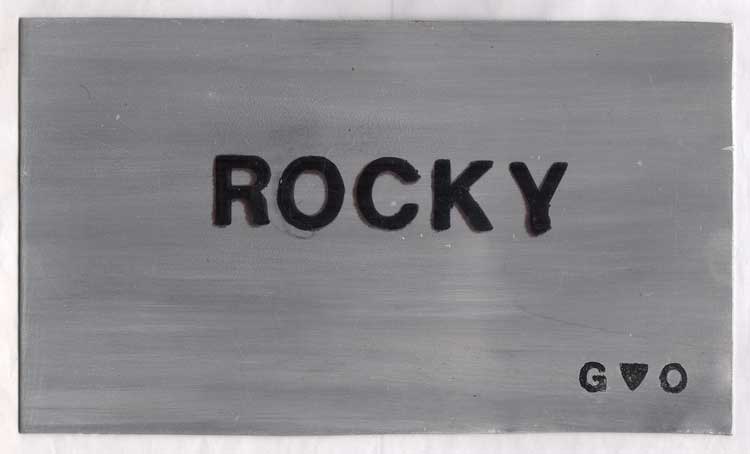

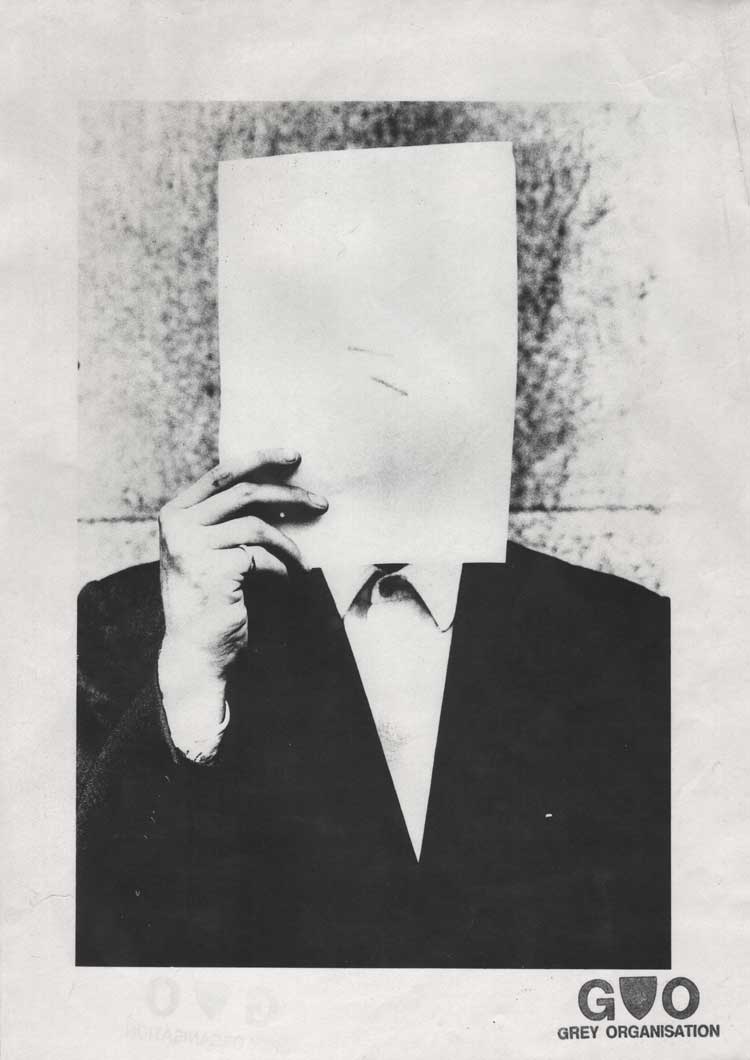

Founded in 1983 and dispersing in 1991, the GO’s core members were Toby Mott, Daniel Saccoccio (né Clegg), Paul Spencer and Tim Burke (1963-2018). Almost indistinguishable with their buzzcuts, austere grey suits and buttoned-up, sans cravate white shirts , the look they were aiming for was Soviet corporate monoculture – the “Polish lab-technician look”, as the social analyst Peter York characterised it in a talk introducing the exhibition. In the ferociously individualistic Thatcherite Britain, the GO was drawn to a collective model of artmaking that scorned the heroics of the lone artist, looking to the constructivists, Art & Language and Gilbert & George as templates. As was de rigueur for most post-1968 European malcontents, although state-educated, the group’s members were mostly of solid bourgeois stock.

[image11]

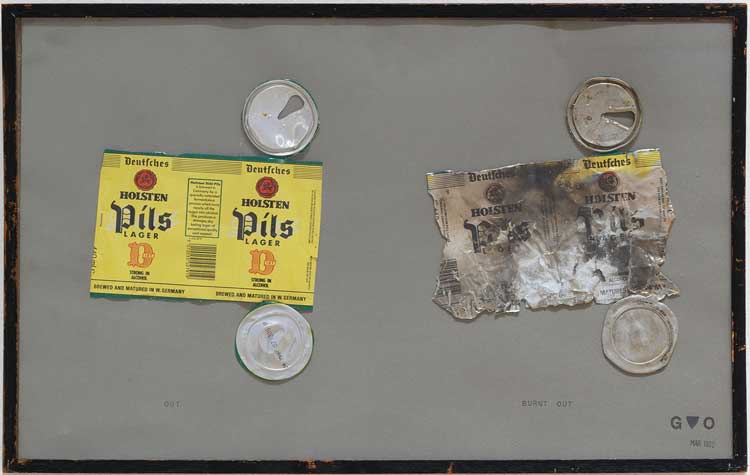

The GO went on to produce varied projects that encroached on many art forms, from paintings made by tracing around their bodies, super-8 and video, typewritten manifestos and open letters, mail art, collections of youth subculture ephemera, and the preservation of the debris of their daily lives: used tea bags, hair clippings and beer bottle caps. Sometimes, they made guest appearances in the work of other nonconformists, such as Gilbert & George and Derek Jarman.

[image12]

Other activities spilled out into a distinctly social domain, including dinner clubs and illegal drinking events, but also direct actions such as the invasion of a booth at an art fair in London’s Olympia and, most conspicuously, the Cork Street Attack. These performative intrusions derived from a long line of more or less belligerent collectives intent on critiquing the social and artistic old guard, from the dadaists and vorticists in the early 20th century, to Guy Debord’s Situationist International in the 60s.

Curated by William Ling, the current exhibition is dominated by the life-size reproduction of the splattered gallery front shortly after the incident, a suitably grey-tinged photograph that conveniently – for the purposes of the decidedly meta nature of the show – includes the proprietor James Mayor. Further documenting the attack are court summonses, police witness statements and a note from the GO’s solicitor, attesting to a remarkable self-awareness that all this would one day be art: “I now enclose the prosecution papers in your case, for your portfolios!”

[image9]

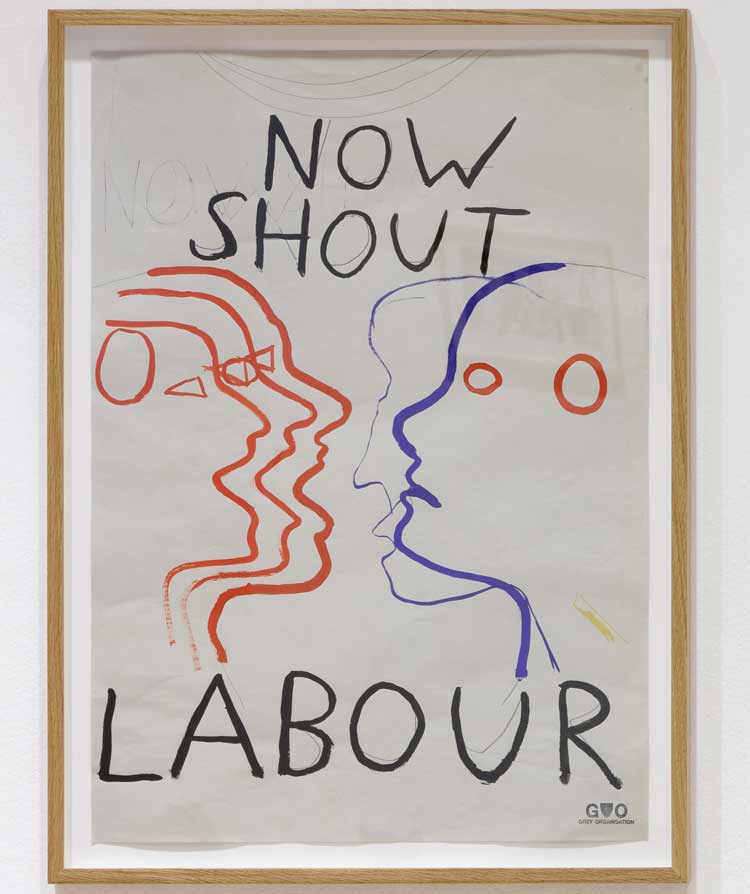

Also on view is a capsule array of other GO works. Taken under the flamboyant wing of the PR grandmaster Lynne Franks, through her patronage the group obtained commissions from Swatch and the Labour Party, and some drawings made for the party’s 1985 election campaign are on display.

After the Cork Street attack, the GO eventually decamped to New York and the sunny album cover art for De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising was one of the notable works produced during that period, for which preparatory designs are included in this exhibition.

[image8]

In a report of the raid in Art Line International Art News, the justifications for the group’s rancour vis-a-vis their gallerist victims ranged from the banal to the more disquieting: Waddington was “too busy to get involved in art, said he had some old canvases to sell”; Kasmin was only interested in abstract art with no content as it couldn’t be criticised; Nicola Jacobs “had to go shopping in South Molton Street”; Robert Fraser (AKA Groovy Bob) “said he’d show us if we were gay and would sleep with him”; “The Mayor Gallery said they were digging up dead artists.”

Mayor was, in fact, showing the work of Harold Shapinsky, an abstract expressionist who was still very much alive and had been rescued from oblivion thanks to the zeal and imagination of the life- enhancing Akumal Ramachander, a teacher who set out from Bangalore determined to make the powers that be install Shapinksy into the canon of the New York School. He succeeded, and this fairytale of sorts echoes the Cork Street attack in the way that it challenged the status quo of the art world.

[image5]

Following an artist’s talk to launch the opening of Cork Street Attack, an audience member asks Mott: “Have you sold out?”

“Yes,” is his unhesitating retort, and Mott, now more Jermyn Street than Tower Hamlets, seems to have no qualms about adapting to changing winds in ways that best suit supply and demand. Observing that his punk(ish) contemporaries’ entrepreneurial impetus eventually turned many of them into investment bankers, Mott estimated that this type of buyer didn’t want to be subjected to viewing the printed artefacts of their youth in the insufficiently plush surroundings of, say, a pub. Long before the present exhibition, he obliged by showing items from his copious archives in the reassuringly well-heeled ambience of a gallery in Mayfair – still, despite everything, at the persistent, if not inflexible, heart of the British art establishment.

Each party now comfortably ensconced on the right side of the glass, it’s smiles all round, and any animosity that might have arisen from the GO’s brazen stunt all gone.