by JILL SPALDING

There is Before Christo and After Christo. Tell him that and his eyes roll, but to admirers of heroic interventions it is quite clear. In a universe where size matters, big things have been undertaken since the beginning of time, or at least from the moment that labour was conscripted, materials assembled and leveraged buildup engineered.

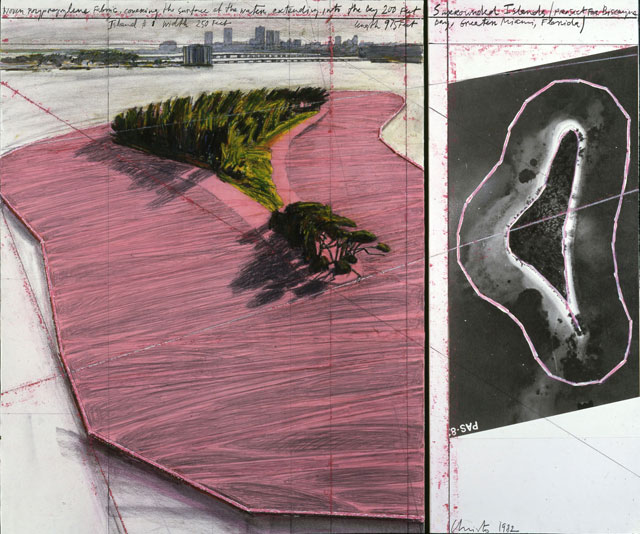

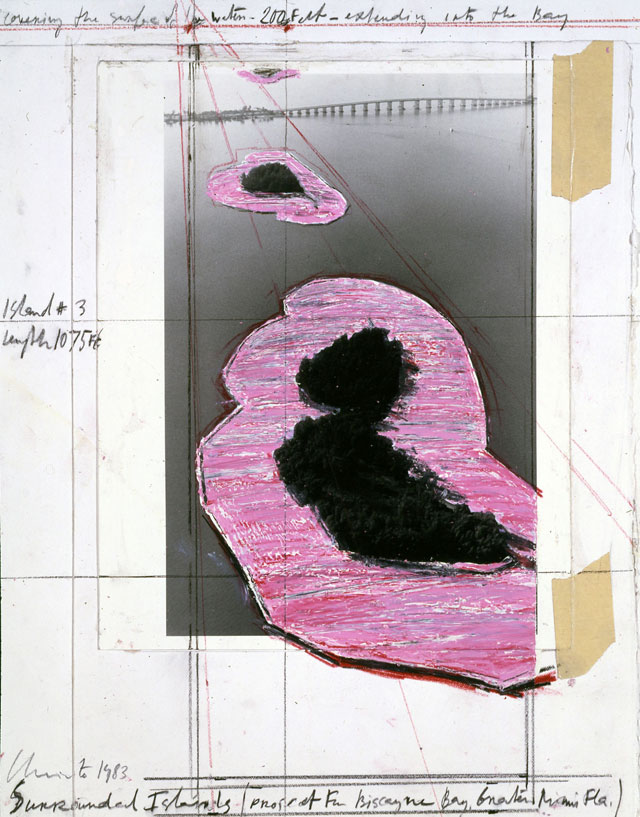

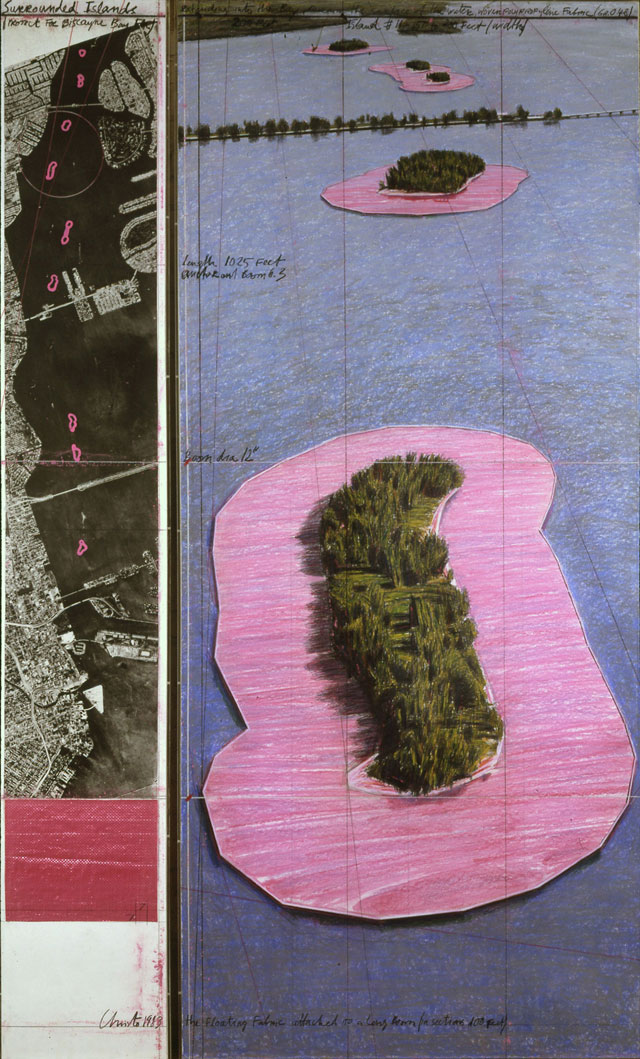

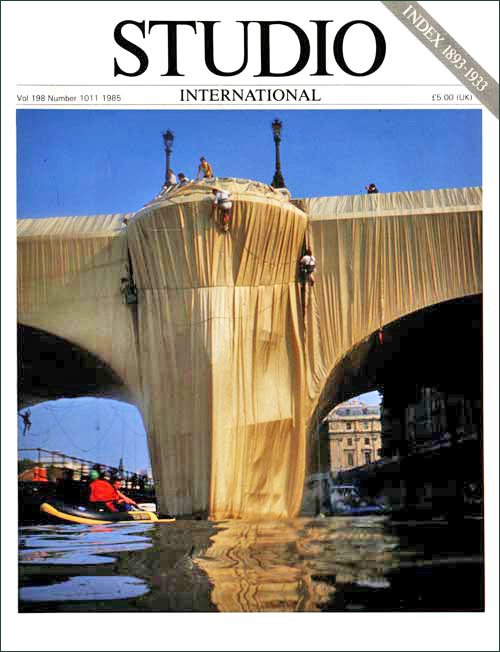

Who really saw the Pont Neuf in Paris before it was dressed? The coast of Australia before a sizeable chunk of it was trussed? Those 11 small islands anchoring a Miami lagoon before they floated pink skirts? Anticipating Christo’s imminent visit to the Perez Art Museum of Miami to talk about their exhibition of that famed installation, I stopped by his New York residence to review his career.

[image4]

I have known Christo for some time, although never one on one. After he met Jeanne-Claude in Paris in 1958, where he was eking out an immigrant-living as a painter of portraits, she was joined to him at the hip as wife, collaborator, gadfly and (frustratingly to both the powers that be and those seeking his thoughts) spokeswoman. It has been almost 10 years since she left us, but the palimpsest of her contribution infuses the projects still in development: Christo speaks of her in the present tense and has enthroned her in the cadre of counsellors that presents as their court.

[image5]

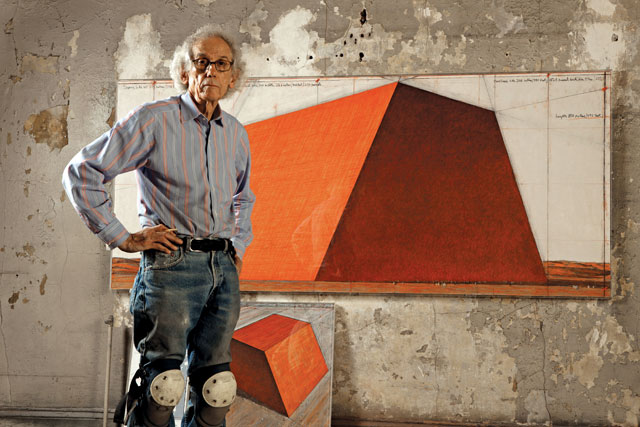

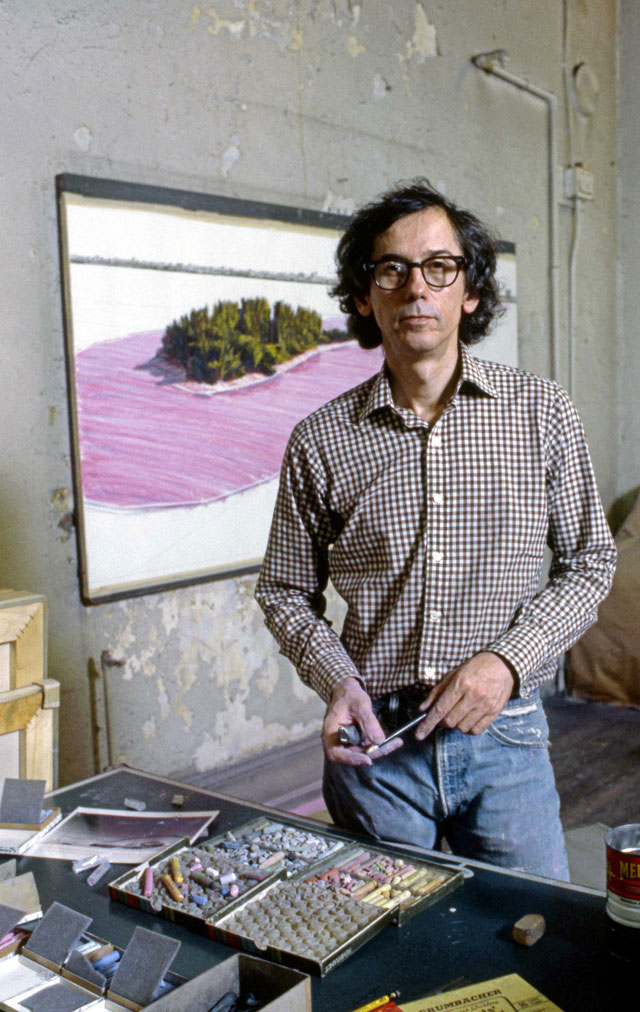

So it was with disbelief and relief that I found myself seated across from him, no one else in attendance, in a studio of sorts, incandescently lit and hung with drawings of one failed, two realised and one incipient project.

After the offer of tea, there was no more small talk. I told him that I would not be asking the usual questions or going over ground already well covered. Having attended numerous presentations and read myriad interviews unfolding the same litany of immigrant background – (born Christo Vladimirov Javacheff in Bulgaria in 1935), formal art education (abandoned halfway through), first wrapped packages (group show, Paris 1958), first personal show (stacked barrels, Cologne,1961) – I had carefully prepared questions that, to my recollection, had never been asked of him.

[image6]

To no avail: bent on chronological narrative, Christo worked each question into established biography. He said it was critical that I register the trauma of statelessness; the artistic swirl of Paris overwhelmed by its alienating attitude to immigrants; the struggle to break free of “refined” art, “art that smells nice”, in very controlled gallery spaces – a liberation realised with the unfettered, urgent collusion of Jeanne-Claude in the 1961 portside installation, Dockside Packages.

There followed a rat-a-tat sequence of the early projects conveyed with a baton of hand movements in a rapid, heavily accented speech punctuated with bursts of enthusiasm that would topple you in a wind tunnel.

The few questions I could interject received abrupt answers:

Which comes first, the site or the concept?

“Sometimes the site, sometimes the idea.”

Do you think of yourself as a multimedia artist?

“I don’t know what I am; sculptor? painter? architect?”

When did Javacheff become Christo?

“From the very beginning – even as I was signing the portraits ‘Javacheff’, I was signing the wrapped packages ‘Christo’.”

What brought you to the wrapped object?

“All those ideas were in the Paris air in the 50s – I was very influenced by [Jean] Dubuffet for the rich surface of the cast ones.”

But wrapping as a concept, did it address secrecy? Metamorphoses? Imminent revelation?

“Oh, no, nothing like that. It was more about cheap materials and variable forms.”

There were nuggets, nonetheless. Leaning in as though picking a recollection apart, Christo added: “They were poor things, like me – miserable, transitory and, in a short time, they’d be gone.”

[image16]

He said much the same of those painted drums in Stacked Oil Barrels and the Dockside Packages he and Jeanne-Claude stacked by the Rhine in Cologne in 1961: “The harbour was closed and the material was in stuck in transit, so we borrowed it for two weeks”; of the first street intervention, Rideau de Fer (Iron Curtain; 1962) at Rue Visconti in Paris, and of a larger installation along a highway in Gentilly: “They were an inexpensive way to build up.”

Thinking to be laughed off the island, I asked if he had ever thought of wrapping a person. “Of course! In London and Dusseldorf, in 1963, I wrapped a naked woman. At the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, in 1968, I placed several wrapped women on bases. It was wonderful. The Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Marrakech will be showing them in 2020.

Temporality was the link. Once their practice moved out of the gallery into rural and urban spaces, impermanence became the sine qua non. Christo cites budget. “You cannot imagine how much the maintenance of an outdoor project cost us – just for the staff and the rental. And every penny paid by us.” This last could have stood as a refrain for his recounting of the feats involved with each work – the figures seared in his memory; $3m for Valley Curtain, $15.3m for the Wrapped Reichstag.

[image14]

I asked how addressing a rural space differed from an urban one. “Both are borrowed spaces and while we inhabit them everything in them becomes part of the work – the water, the bridge, the rope – so that we are always dealing with the real thing, not a photograph of it, not a video of it, the real thing.”

Both, too, are intended to create “gentle disturbances”, but for a rural one they must have distinct points of reference – a telephone pole, say, or a bridge, to provide scale.

Scale in the Christo vocabulary is as much an aesthetic as a mathematical device, as much philosophy as engineering. The elements, too, serve as guidelines. Wind, the rush of a river, the flow of a current, all are addressed by a fleet of professionals with models built to scale in a similar but undisclosed, rented, location – a small stretch of coastline wrapped for Australia’s 2.4km long Wrapped Coast (1968-69), a private ranch to test the curtain to be strung across the Arkansas River. Some pushed the environmental envelope too far – wind brought down Valley Curtain in Rifle, Arkansas, after a day – but so be it. The drawings and documented permitting process gives it viability. For Christo, “the energy of the elements is a necessary part of my existence” and viewer participation exacts the voluntary surrender to extremes of climate; “wet, dry, warm, cold, dark, light”. A successful work has to communicate that energy and evoke elemental emotions from the seemingly serendipitous but intentional interventions – wind rippling fabric, sun glistening on water and late afternoon shadows – constituting the sense memory that alone will endure.

[image8]

Since each of the elements of an installation delivers a unique energy, each must exist on its own and be “free” to breathe, “free” of bureaucratic constraints. The insistence on autonomy comes up again and again, growing more emphatic when I ask if each project had a different goal. “Oh no, all the projects are totally irrational and absolutely unnecessary. Each is specific to a place and a time and cannot be repeated. That’s why we never accept commissions.”

Artistic freedom may be paramount, but the sheer complexity of the massive outdoor installations entails reliance on teams of professionals and paid volunteers – engineers, physicists, mountain climbers, rafters, installers. Christo nonetheless insists that he maintains total control, seeks little advice and admits to no authorship but his and Jeanne-Claude’s, because they had worked out the logistics and all were “technically simple”.

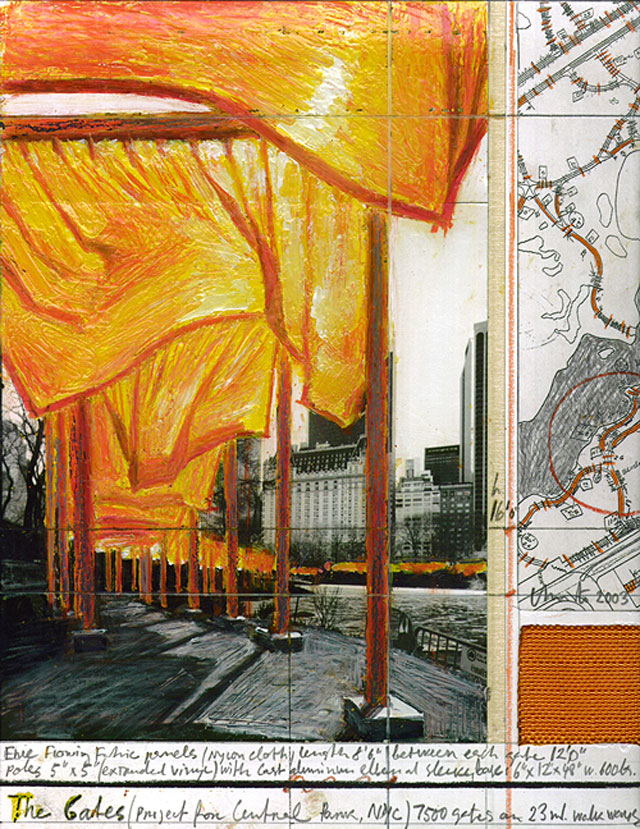

Simple in the Christo vocabulary translates as heroic; 500 workers to dress the Pont Neuf; 603,870 sq metres of pink fabric for Miami’s Surrounded Islands; 3,100 umbrellas marched down the coasts of Japan and California to link the two continents; 7,503 gates marched through Central Park; 9.5km of silver fabric panels to be hung for Over The River at eight locations along the Arkansas River.

[image17]

Tellingly, visitors experiencing a finished work don’t note the statistics. Nor the site’s secret narrative. It is the majesty that marks, the sheer impossibility of it all. Those of us who walked The Floating Piers (2016) across 3km of Lake Iseo, as realised by 200,000 high-density polyethylene saffron cubes stretched between two islands in Italy, engaged thoughts of precarious balance, Jesus Christ or visual beauty – but the project’s hidden dimension of the “horrendously deep ice age chasm” that a misstep would access by the intentional absence of railings was understood only by Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

Where they remained totally dependent was on the permissions. It ever had been so (46 projects refused for 22 realised – the Reichstag alone was refused three times before approval), but especially now, without the combative skills and fierce confrontations of Jeanne-Claude, Christo’s established fame weighs little against an obdurate establishment – the mayors, ministers, presidents and, latterly, emirs, who give the thumbs up or down to the ultimate scheme. Permits served as the interview’s undercurrent – again and again, Christo interjected them. The last work installed illegally was Iron Curtain, his immigrant answer to the just-built Berlin wall; permission refused, it was put up at 10pm and came down seven hours later.

If “free” is the Christo mantra, “politics” is the basso continuo. Could an interview have a crescendo, ours built to a frenzy of permits sought, granted or refused; years, decades of quixotic battles against the windmills of bureaucracy, public protest and even – permission within months of obtaining – a sudden changeover of the political guard. The years of battling for permits to green-light Over the River proved so frustrating that Christo finally tired of it and £7.85m into paying for it, cancelled it.

“Jeanne-Claude and I are nobody in the world of power; we only exist when we are accepted by the establishment,” he repeats twice, with a fervour that is almost ecstatic. He freely admits, “I love to challenge the status quo”, but when I ask if he has relished the controversy, if controversy had become a vital aspect of process, he pushes back with mock fury.

[image19]

“What do you mean? I am not a masochist. Why would I want to spend years and years fighting? And pay for it. We’ll get to the big Mastaba later” – that chronology again – “but you should know that for my last visit to Abu Dhabi I hired Mrs Madeleine Albright – I had to pay her company, of course – to personally fly with us and intervene with the emir, because she has direct access, and without him our project could go nowhere.”

Nowhere, too, without funding, meaning self-funding, a feat they pulled off by beating capitalism at its own game. “I studied Karl Marx in school and, though I may be anti-corporation, I am not anti-capitalist – in fact, we work closely with banks; Citibank, Credit Suisse, so many others.”

But what of his own for-profit corporation, identified by his initials, CVJ?

“But, of course. How else can I pay my large staff? All those workers, those trips, those materials. We have never been beholden to anyone and must remain independent, existing completely outside the context of institutions and galleries.”

I remind him that, although he is famously reluctant to talk about process, he has been eager to document it – each iteration, each adjustment, has been closely recorded. What is he showing with the drawings if not process?

“It was essential to document each phase and all the components of that documentation are integral to the project: they are the project. And, of course, we had to have work to sell along the way because (he jumps up for emphasis) we are completely self-funded.”

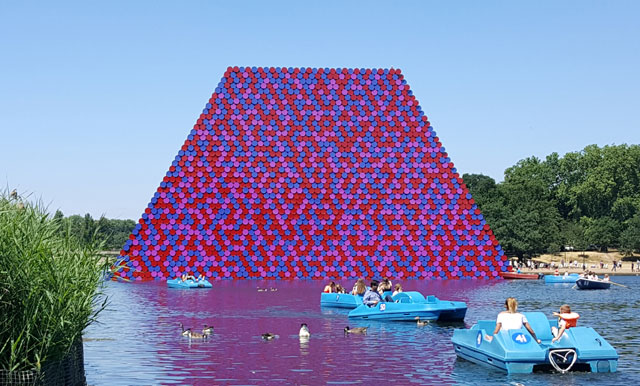

He says he never revisits a project, but can we talk now about the Abu Dhabi Mastaba? He had built small ones in Paris and then in Cologne. There was the one planned for the Reichstag Museum that he never got permission for; the scaled-down one that he erected at the Giacometti courtyard at the Maeght Foundation in 2016; the larger one that showed last year at the Serpentine Gallery, and several others along the way that never materialised.

[image15]

“That’s all one long story because Jeanne-Claude and I had envisioned the big Mastaba for Abu Dhabi back in 1977 – we even found the location, this gorgeous stretch of desert – but didn’t have the resources or connections at that time to realise it. So, we built smaller models, but all to scale, always to scale – down from the projected footprint for Abu Dhabi of 150 x 200 x 300 metres to, last year, 20 x 30 x 40 metres for the Serpentine. That one may save us. When we hit a wall with the Emirate, the director Hans Ulrich Obrist said, ‘Let’s bring the preparatory work to London and stage it as an exhibition’, and we immediately agreed, knowing we could use the scaled-down model to show the royal family.”

[video1]

The London Mustaba. © Christo.

All the while, Christo has been pulling out books from a stack lying conveniently on the coffee table – this one illustrating the developing stages of the Abu Dhabi Mastaba – scaled on the page to show its gigantic footprint handily enfolding the Vatican’s St Peter’s Basilica and even, astoundingly, the Pyramid of Giza. His elation recalled a long history of pride laced with hubris (I thought back to that 1893 Chicago World Fair moment that announced the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building as large enough to contain that same Vatican cathedral.)

What, then, is the problem? What could the Emirate, so eager for landmarks that it built the world’s fastest roller coaster, possibly object to?

“It’s too far away. The desert area we propose is 120 kilometres inland, close to the Saudi border – we scouted miles of desert and nowhere else has the same sweep and beauty. But they are not at all interested in something completely out of sight – they want it right there, in that ugly city of tall buildings, just another tourist attraction. No, no, it needs to exist in a completely free space – we have specified a protective area of 6 sq kilometres on which nothing will ever be built aside from good access roads and the little hotel you see here, all of which we will build, pay for and maintain.”

[image18]

This next trip may nail it. Straining at the bit of travels scheduled by the hour, Christo left for Abu Dhabi two days after our interview and from there headed to Miami to oversee and talk about PAMM’s installation of rarely seen Surrounded Islands material.

[image9]

I ask what else lies in the future and he references three forthcoming projects. I hope for a scoop – “No, no (that gleeful chuckle again), it’s a secret. I can tell you there are three new things, one in the works, but I cannot tell you anything about them.”

I deduce from what follows that all will be big and outdoors – “I must be in nature. I enjoy the energy of the elements, it is a necessary part of my existence.”

Given that even a weather whisperer must eventually move on, I ask what will happen post-Christo to the unrealised projects. Might they be revisited? He bristles: “Of course not. Once a project fails to get permits or we tire of it, it’s over.” Unless, he adds, one is very close to completion.

[image8]

Nonetheless, Christo obsesses on immortality. Whether failed or abandoned, each undertaking has been obsessively documented. Foundational to the drawings sold as individual artworks during each project’s planning stage, a huge scale model, together with the vast documentation of photographs, drawings, permission letters, samples of every material incorporated – fabric, hooks, anchors, rivets, ropes, poles – has been stored in a vast warehouse in Basel, Switzerland. The model, together with 300-500 sample documents can be sold as an entire installation to a collector or museum on condition that it never be separated. In 2010 the Smithsonian showed and acquired Running Fence (1976), but since the cost of even staging one is prohibitive the others remain for sale, travelling to the world’s museums as freestanding exhibitions. On no account may the components be separated. Holding every installation to be a single artwork, Christo returned more than once to the “stupidity” of museums and collectors who ask to buy a “flag” or a “barrel”. “One Gate is not a sculpture. Would the Louvre ask for one arm or one leg of a sculpture?”

It has taken some time for cities to acknowledge a work’s collective importance. The Reichstag installation now occupies its second floor and Paris will at long last honour the transformational aesthetic moment of dressing and undressing the Pont Neuf to reveal it anew with a massively documented exhibition planned for the Pompidou in 2020.

[image3]

Has he thought about a retrospective?

”Retrospective? What for? I refuse a retrospective!”

Might that partially be due to the time it would take from the ongoing projects? The reason, he gives, for example for why he won’t teach: “I have no time, I am always travelling, and why do I need to teach when I am always communicating? No, what matters to me now is that everything I do is for my enjoyment. That I pay with my own money. That I am free. I want the rest of life to be a marvellous journey.”

Thinking to save the cosmic question – the one I thought he would relish – until last, I asked what he thought Christo had brought to the canon of art. “Ha!” He bristled at “canon” and bristled at “art”. “Art is useless!” Were he not a person of the world, dependent on people if not on their pronouncements, he might have waved my question aside altogether.

Still, he did not seem displeased by it, nor by my proposition. As I see it, I went on, before Christo a great work was constructed for the ages and presented itself to the eye when revisited. After Christo, a work built to intervene with its surroundings for a strong visual moment remains, in the mind’s eye, a timeless mirage. The memory of a Christo is the artwork: its aesthetic, the residue. Then I braced myself.

Christo leaned in again, threw up his hands one more time, smiled, and said nothing.

[image11]

Postscript. Christo will be visiting Miami on 4 December to talk about PAMM’s exhibition of the Surrounding Islands material that remains in his personal collection. It toured through Europe and Japan in the 1980s and 90s but has never before been presented in the US. He will also be talking about work pertaining to other outdoor installations drawn both from private collections in Miami and from PAMM’s own collection (The Gates). The Surrounding Islands exhibit will remain on view until 17 February 2019 and then return to Christo.

I asked the museum’s director, Franklin Sirmans, what exactly will be displayed. “We are showing everything. Approximately 50 drawings and collages; a large-scale model; hundreds of court records, multiple sizes and uses of photography, both documentary and ‘fine art’ product, if you will. The actual material that surrounded the islands will be displayed for the touch.”

• Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Surrounded Islands, Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida, 1980-83 – A Documentary Exhibition is at the Pérez Art Museum, Miami, until 17 February 2019.

.jpg)

.jpg)