Whitechapel Gallery, London

28 August 2021 – 2 January 2022

by EMILY SPICER

The Whitechapel Gallery’s latest exhibition takes visitors on a nocturnal tour through dreamscapes and dramatic landscapes, from haunted forests to wild Nordic regions inhabited by trolls. The works in this exhibition have been chosen from the Christen Sveaas Art Foundation by the Norwegian artist Ida Ekblad, whose own varied practice incorporates painting, sculpture, performance and poetry. With an eye on folklore and the macabre, Ekblad has used WH Auden’s poem The Night Mail as her starting point. The poem details the journey of a train through the Highlands of Scotland. Ekblad’s selection, however, takes us on a European tour, replacing the cosy descriptions in Auden’s verses with far more gothic images.

[image4]

The exhibition is conceived as three train carriages and explores the psychological aspect of travelling at night alongside more literal representations of moving through the landscape. Harald Sohlberg’s watercolour Winter Night in the Mountains (1911) depicts the Rondane Mountains in Norway in a symphony of blues. A prophetic star glitters between two snowy peaks that are framed by bare and gnarly trees. Sohlberg made several versions of this painting. “The longer I stood gazing at the scene,” he said, “the more I seemed to feel what a solitary and pitiful atom I was in an endless universe.” In Sohlberg’s chest, there beat the heart of an 18th-century romantic painter.

[image3]

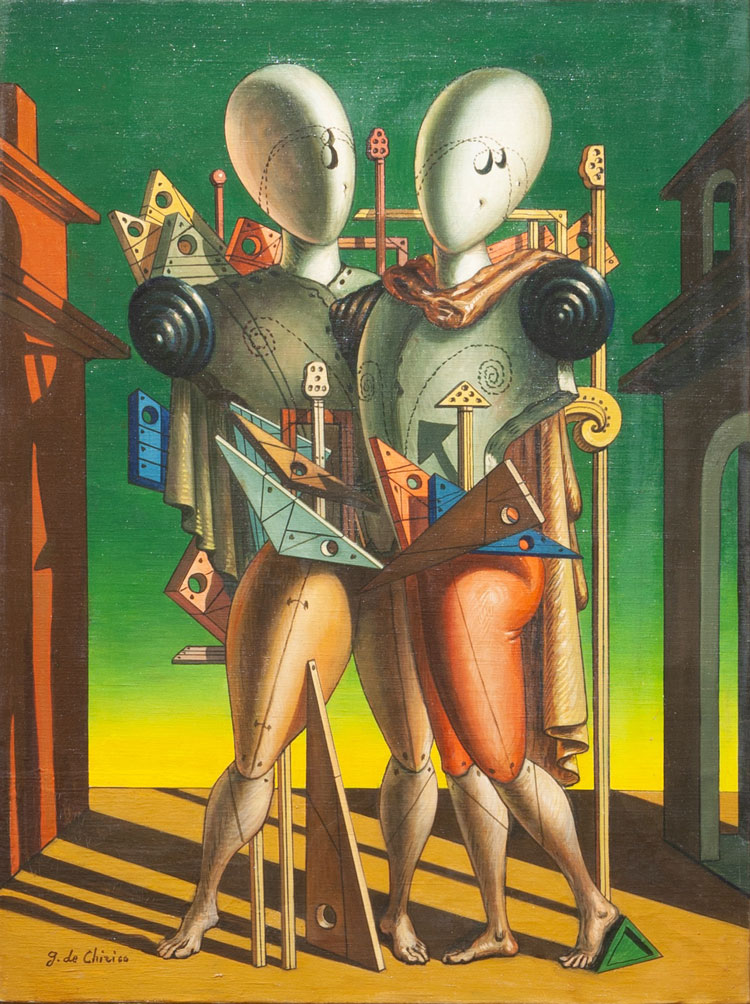

Travelling often excites feelings of wonder and curiosity, but journeying at night can make one feel introspective and even vulnerable. Ekblad has explored this sense of alienation, of being removed from the world around us by the darkness and quiet of night, with some surreal offerings. Take, for example, Giorgio de Chirico’s Ettore e Andromaca (1959). Lifted from Homer’s Iliad, the scene depicts the farewell between Hector and his wife Andromache as Hector leaves for the Trojan war. De Chirico’s version sees two armoured mannequins wrapped in mechanical apparatus. It serves as a meditation on love and war but, as with all surrealist paintings, it also deconstructs reality, serving to disorient the viewer from a sense of time and place.

As our train hurtles through the gloom, we perhaps doze off awhile and the unfamiliar surroundings work their way into our subconscious. We feel unsettled and dream of nightmarish happenings and ghoulish goings on. Andreas Bloch’s Man with Helmet and Young Boy on Horseback (1890-1910) depicts a Nordic character galloping through a dark forest. A small boy clings to him as they are chased by four spectres under the light of a full moon. Ghosts are not the only thing haunting these lands. There are trolls hiding in the mountains, too. Theodor Kittelsen’s Forest Troll (1905) trudges through the trees, so tall it can see over the tops of the pines. Its face is haggard, its hair long and grey. One of its eyes glows a devilish red.

[image5]

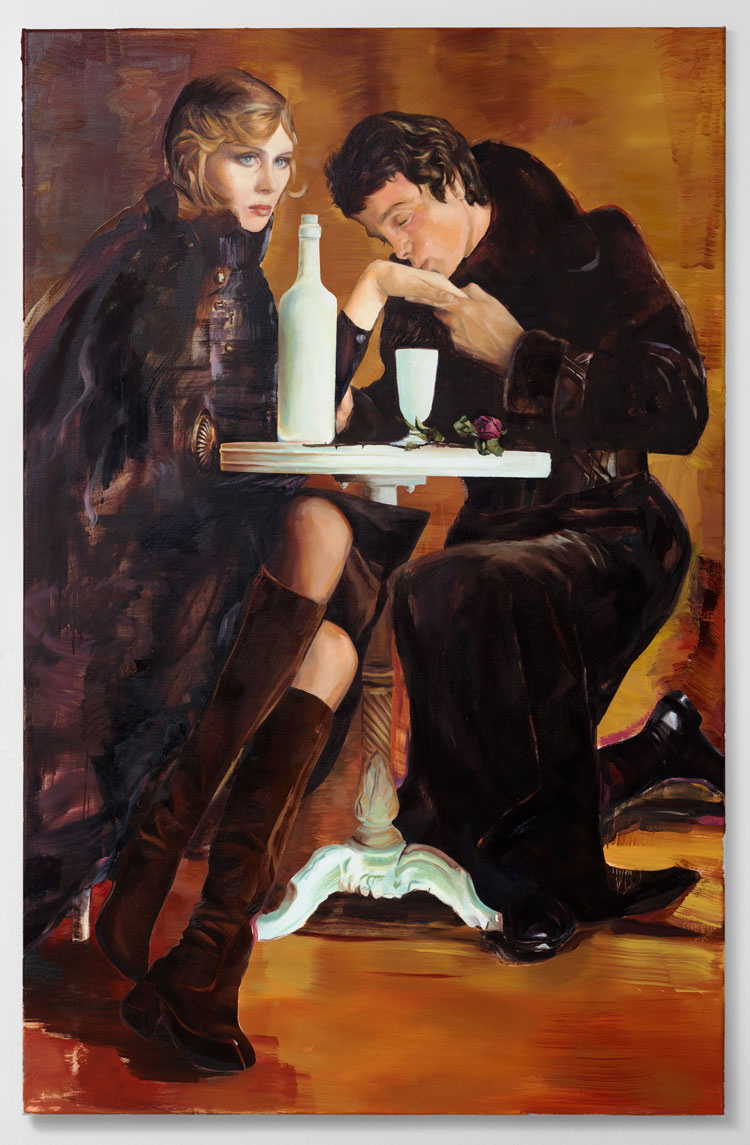

But, if we are in a sociable state of mind, a night train might offer us more congenial distractions than ghosts and ghouls. A display of elegant antique glass and silver tableware suggests fine dining and wine. Paulina Olowska’s painting Seductress (2020) adds a note of tragic romance to the gallery. The image has a distinctly 1920s feel about it, as our femme fatale, a woman with blond, cropped hair, looks away with a bored expression as a young man in a Dr Zhivago coat kneels by her side and kisses her hand.

[image2]

Anna-Eva Bergman’s Planete Argent (1973) gives us a silvery full moon to contemplate from our seat. But the full moon brings with it madness, signalled, perhaps, by the dark, swirling canvases of Edvard Munch, an artist who was famously hospitalised after he suffered a nervous breakdown. Perhaps our imaginations are running away with us. If so, Ed Ruscha’s Painkillers, Tranquilizers, Olive (1969) offers us a possible cure. The tablet-shaped objects appear to fall (or are they floating?) against a red backdrop that darkens to black. It is a simple, dream-like image, another surreal mind-space tempting us away from our waking thoughts.

[image1]

This exhibition is full of gems, but at times it also feels like a curated jumble sale. Nineteenth-century cartoons of clothed animals sit alongside abstract works; a watercolour of blue breasts by Tracey Emin occupies the same section as paintings by the 19th-century Norwegian realist Christian Krohg. Theaster Gates’ Migration Rickshaw for Sleeping, Building and Playing (2013) is so crammed into the divided gallery space that you find yourself edging around it, rather than standing back to really see it. But there is also a sense of discovery to be had. And time spent scouring the walls will be rewarded.

![Anna-Eva Bergman, Planète Argent [Silver Planet], 1973. Oil and silver leaf on plate, 60 x 73 cm. Courtesy of the Christen Sveaas Art Foundation.](/images/articles/n/072-night-mail-2021/Anna-Eva-Bergmann_Planete-argent.jpg)

![Harald Sohlberg, Vinternatt i fjellene [Winter Night in the Mountains], 1911. Watercolour on paper, 57.5 x 65 cm. Courtesy of the Christen Sveaas Art Collection.](/images/articles/n/072-night-mail-2021/Harald-Sohlberg_Vinternatt-i-fjellene.jpg)