At the time of writing, the Olympic torch continues to make its troubled way around the globe, the protests which accompany its passage sparked by the Chinese government's repressive reaction to both peaceful marches and violent riots in Tibet. In its uncritical eulogising of creative industry, this exhibition skates over the paradoxes of contemporary China, and does too little to advance the cause of mutual understanding.

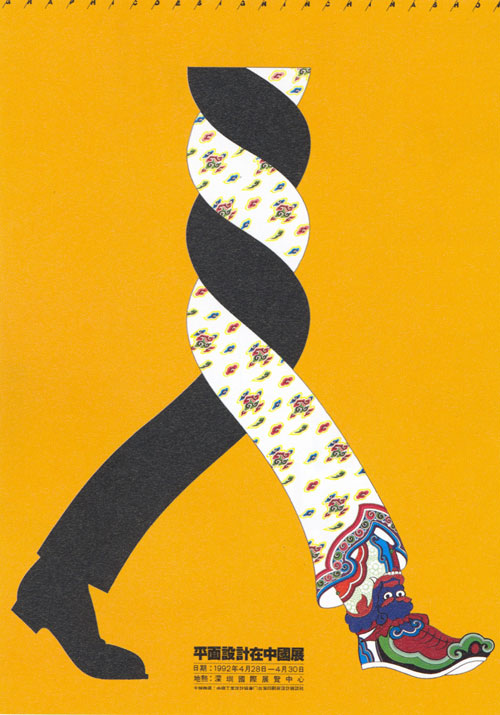

If objects both encode and influence ways of perceiving and being in the world, then a design exhibition provides an excellent vehicle to explore the ways in which individuals, collectives and companies are creating and disseminating new interpretations of cultural identity. Indeed, the show starts in a promising manner, looking at the graphic design boom in the Southern city of Shenzhen in the early 90s. The rapid transformation that turned a group of fishing villages into a special economic zone bordering Hong Kong, and subsequently a city which today has 10 million inhabitants, is reflected in posters by pioneering graphic designers both north and south of the border. The exhibition-s designation of Shenzhen as a 'frontier city' seems apt in the light of a poster by Freeman Lau for Fifteen Hong Kong Graphic Designers (1994): a matchbox in the corner is emblazoned 'Hong Kong-, while in the centre a star formed from burning matches evokes Mao's ambiguous slogan, 'A single spark can start a prairie fire'. As the successful testing ground for a new 'Socialist Market Economy', Shenzhen was well placed to benefit from a dialogue with Hong Kong and beyond, as exemplified in the bold and inventive work of graphic designers such as Wang Xu and Kan Tai-keung. A further series of works, grouped under the banner 'Ideograms', showcases the ways in which contemporary graphics exploit the possibilities of Chinese characters and traditional calligraphy. One of the most interesting pieces is a book designed by Guang Yu, Catalogue of Paintings by Chang Jin (2004), in which traditional thread binding, with holes stabbed through the left-hand margin, has been adapted so that the threads connect to form the artist-s name.

The exhibition focuses on three cities as emblematic of modern China, emphasising Shenzhen's youth culture (the average age of the inhabitants is 27), as well as its frontier status. Hence we get a crash course in design associated with various underground music scenes: rave zines, CD covers and rock videos. An interesting video clip investigates the tradition of a 'flea market' of home-made pin badges and T-shirts at Beijing's Midi Festival, China-s largest outdoor music festival. The DIY tradition is being undermined as informal trade is curtailed and international brands like Gibson muscle in on the lucrative market, a depressing story that finds its logical conclusion nearby in a Nike 'Year of the Dog' Air Force 1 trainer, designed by Runyo, PK and HIMM in 2005.

Admittedly, there is nothing especially surprising about the fact that Nike should want to commission special editions of a standard shoe to sell in particular places around the globe. And perhaps the designers are naively sincere when they claim inspiration from Tibetan religious culture and state that environmental protection is a key concept behind the trainer-s design.1 But while one aspect of contemporary China is undoubtedly the rise of youth sub-cultures and their embracing of global brands, it is sad that an entire culture is apparently reducible to the patina on a pair of shoes, to say nothing of the political ramifications of this particular appropriation.

The next room focuses on Shanghai, centre of fashion and 'lifestyle'. A clip from Wong Kar-Wai's lushly-shot film 'In the Mood for Love' (2000) sets the scene: dealing with the romantic entanglements of Shanghai exiles in 60s Hong Kong, Wong-s film has fed a nostalgia for qipao dresses and retro styles. Products from the boutiques in Shanghai's Xintiandi district include Han Feng-s elegant silk dresses, Lin Jing's bird-like teapots and Jiang Qiong Er's jewellery, whilst gorgeously coloured pâté-de-verre glass barstools from the TMSK Café contrast with Shao Fan-s modern take on dark-wood Ming seating. The exhibition at last starts to get its teeth into the matter of social conditions here, with Hu Yang's 'Shanghai Living' (2004-05), a series of photographs which depict subjects, from entrepreneurs to labourers, sitting in their homes. The disparity between rich and poor is underlined by the captions, short interviews in which the subjects talk about their lives, problems and hopes for the future. Meanwhile Xing Danwen-s excellent 'Urban Fiction' series (2004-08) uses photographs of developers- maquettes, to which she adds images of herself as different characters, populating the unreal spaces of as-yet-unbuilt homes with fictions of murder, illicit affairs or everyday life. Her disjointed and lonely characters act out Ballardian scenarios, looking out of brightly lit windows into deserted streets. Although the topic is touched upon obliquely in 'Shanghai Living', no other mention is made of the consequences of these new 'lifestyles- on those forced out of their homes by new construction, nor of the fates of those who advocate human rights. Amnesty International has reported on the case of Zheng Enchong, a Shanghai lawyer, who, 'on 24 July 2007, […] was publicly beaten by a group of around six police officers outside the Shanghai Municipal Higher People's Court after he and his wife, Jiang Meili, tried to register to observe the trial of Zhou Zhengyi, a local property developer. He has since been kept under tight surveillance and blocked and often beaten when he tried to leave his home'.2

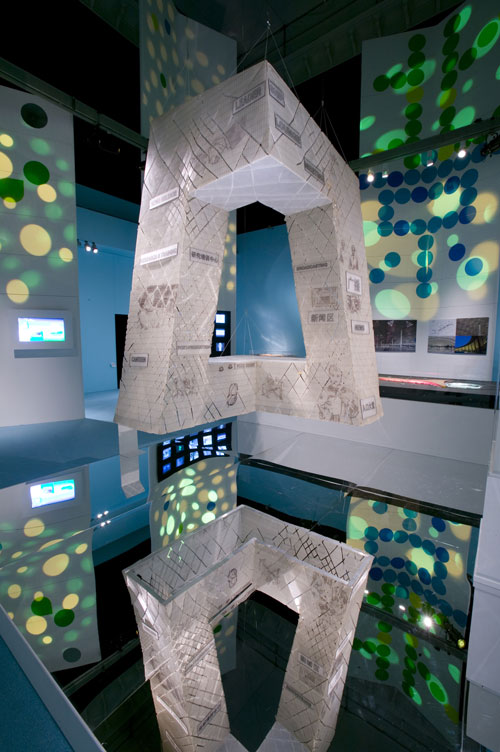

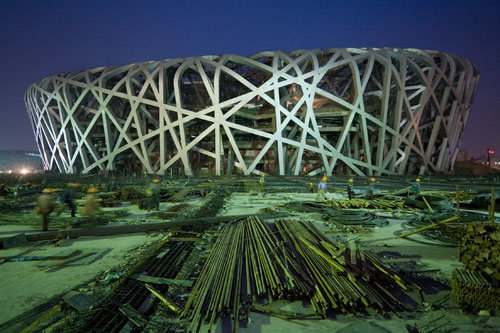

The final room concentrates on architecture, and again the politics of land use is conspicuous in its absence. With some buildings, such as the beautiful and innovative private houses designed by practices such as Atelier FCJZ and Ma Qingyun, this is not an issue. However, the presentation of the Olympics-inspired prestige projects, such as Foster and Partners' Terminal 3 of Beijing Airport, Herzog and de Meuron's National Stadium and Rem Koolhaus's China Central Television Headquarters, is short on scrutiny or even context, considering that London is already embarking on its own grandiose building spree in preparation for 2012.

As a final triumphal touch, a glass case in this room houses one of the Olympic torches, the stylised cloud pattern of which, we are told, represents harmony. Unfortunately, the harmony that this exhibition attempts, by watering down critical debate and in-depth discussion, is misguided. If, following Chantal Mouffe, we accept that pluralism entails conflict, the challenge is to find 'agonistic' modes in which this conflict can be carried out, as opposed to forms in which adversaries become de-legitimised as enemies.3 Although Mouffe-s argument is directed towards specifically political institutions, design, as the crossroads between business, artists, consumers and objects themselves, is another potential arena for encounter and questioning. 'China Design Now' is a missed opportunity to build understanding through debate with the makers and users a global superpower's material culture.

James Wilkes

Footnotes

1. See their 2006 interview with Freshness Magazine: http://www.freshnessmag.com/v4/2006/03/19/

year-of-the-dog-af1-interview/ (accessed 21 April 08).

2. Amnesty International. People-s Republic of China: The Olympics countdown - crackdown on activists threatens Olympics legacy, ASA 17/050/2008, 1 April 2006, p. 9.

3. See Chantal Mouffe. On the Political. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005.