The Cob Gallery, London

10 September – 2 October 2020

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

As we enter the Cob Gallery, we are given a choice of face masks in soft blues, greens, yellows and cream, printed with the word FILTH in an archaic font. There is something so prescient about the timing of Cat Roissetter’s latest show, during a temporary easing of some pandemic restrictions; we are all so preoccupied with filth on so many levels, that to reflect more deeply, albeit with a sense of surrealism and wit, is a welcome way to pass a Thursday evening in Camden, north London.

[image2]

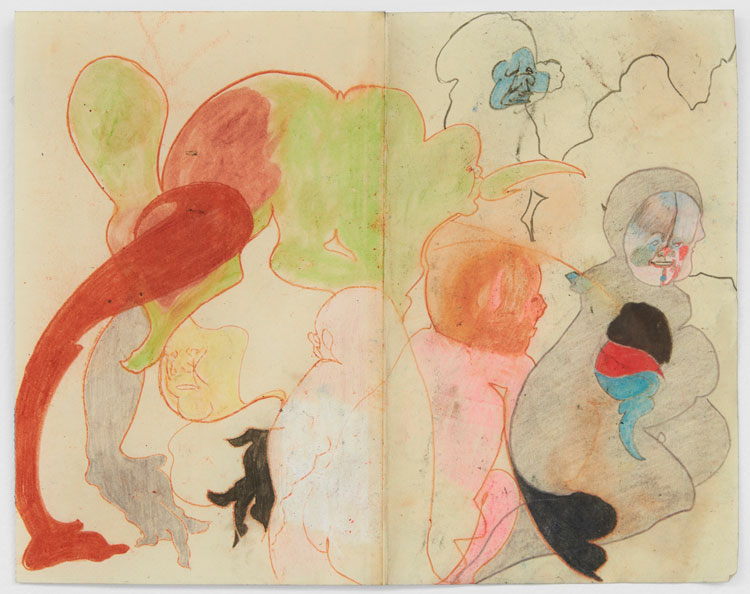

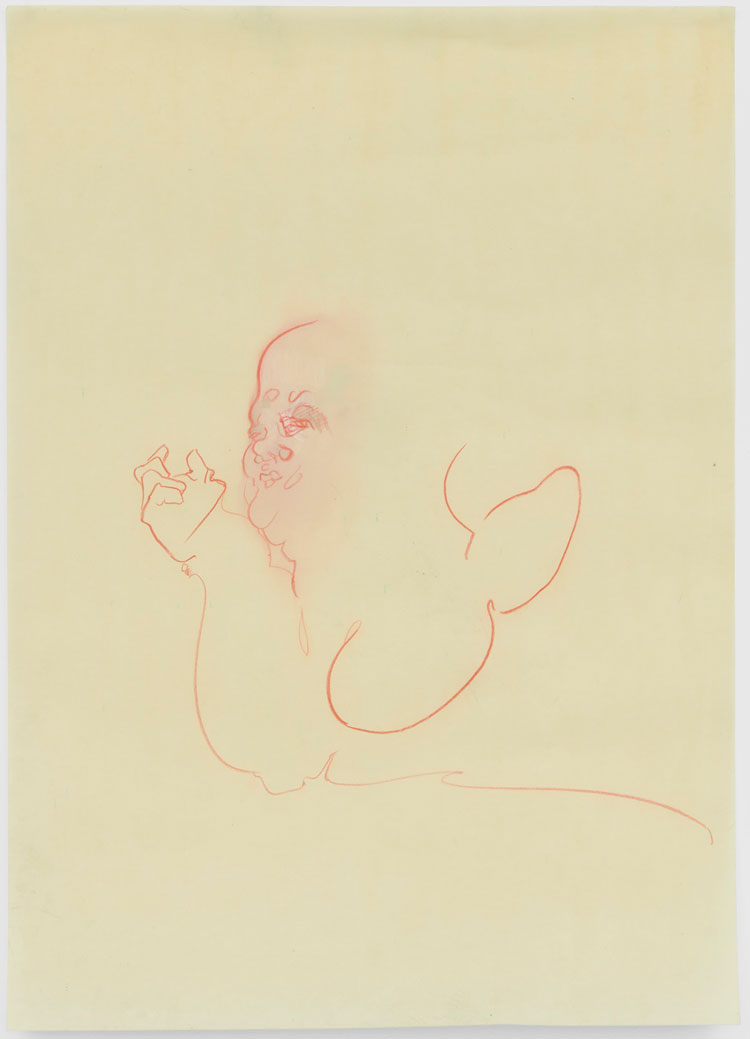

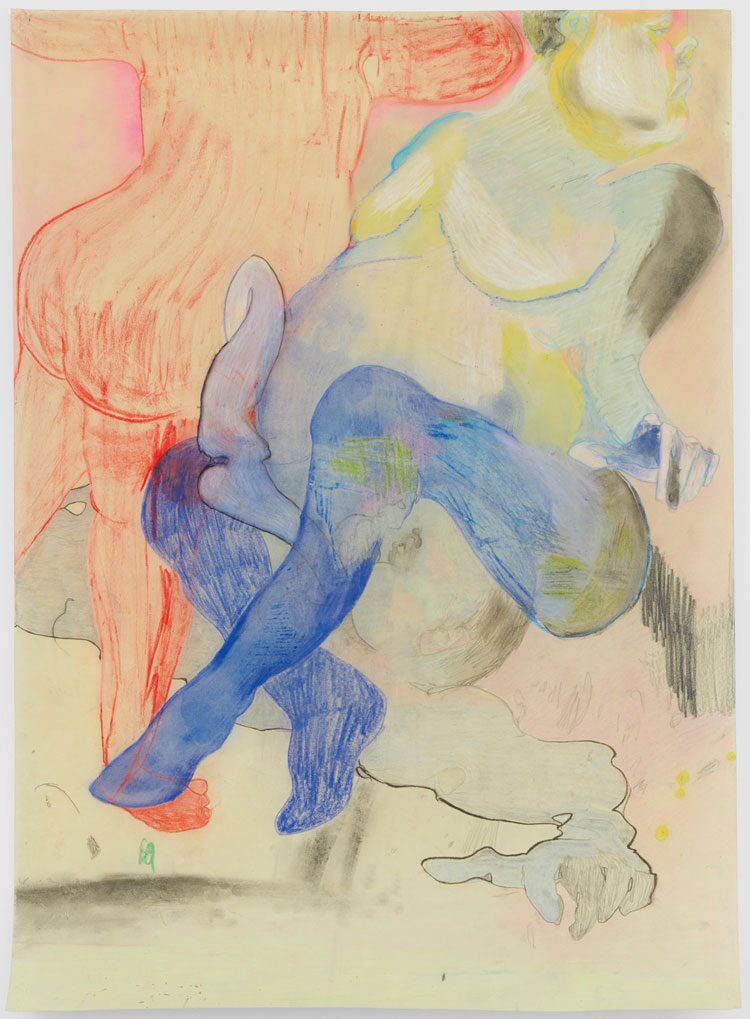

Downstairs, Roissetter’s work – mainly drawings on oil-soaked paper – is immediately wry and entertaining. Ambiguous, leering nudes, who merge into one another (even as they are at times repulsed by each other) are rendered in the vivid colours of a set of children’s pencils, which seem transient in their fluidity and layers, their erased and reappeared lines on degraded paper. The “bubble people”, as my young son describes them, are bloated and yet light; they remind me of the girl who balloons into a giant blueberry in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory; certainly there is an almost childish sense of enjoyment and daring, as these human figures transform, coalesce and fade into one another.

There is, of course, a more “adult” edge to these works (subtle enough that it is clear only to adult eyes, I think). “English filth” refers not just to the materials with which Roissetter works – oil-soaked, crusty paper, hard and transparent like the discarded paper from a fish supper – but also to a form of English culture as familiar as it is often overlooked. In a humorous, mocking way, Roissetter casts light on the duplicity of these social structures: the ways in which a mask of politeness often conceals the vipers and smut, the lewdness and vice, that underlies the “culture” we often export and choose to represent us.

[image4]

Rooted in a Victorian, dualistic and hypocritical morality, this approach to culture is nowhere more emblematic than in the tradition of English portraiture, where nudity is typically absent. The puritanical streak in our history and culture, which presumes that nudity is always on some level a depraved state, transforms natural things into criminality and depravity, something inherently suspicious. So Roissetter gives us the Hyde to English Portraiture’s Jekyll; she shows us Dorian Gray’s portrait in the attic. She creates a visual language that is fluid and complex enough to soak up myriad implications and projections; her art is the oil-soaked paper on to which our ideas and images attach and fall apart, in a process of psychological unravelling, a playful interrogation of our own subconsciousness.

It is interesting, moreover, that, to a child, these images are still just “bubble people”, not sinister at all. So much of our sense of filth is subjective and projected. Here, Roissetter experiments with us, the viewers; we see, to some degree, what we want to see. Her figures are grotesque, but not obscene as such; it is up to the audience to invest them with seediness and vice.

[image5]

In Muster I (2020), for instance, a female figure in blue stockings, her stomach bloated, turns away, her face disappearing into the paper, while a red figure seems to crash into her, albeit opaquely.

[image3]

In Feast (2020), a simple red line drawing, a figure sits like someone propping up a bar, expression wry and detached. In Study for King’s Maid Dream (2020), several figures merge into each other. While the title implies some seediness, the image also recalls a mourning scene, the central character seeming to fade away as he is consoled. Then, in King’s Maid Dream (2020), brighter and deeper in its shades of blue, red and pink, a character is upright and yet overwhelmed by ambiguous blobs; phallic, cloud-like forms surround him.

[image6]

In Slow Poke (2020), awash with pale pink, a central figure seems to dominate another, as a third person looms over them; though the palette is dreamy and soft, there is, just in the slight facial expressions, an implication of some subdued terror here, too.

Roissetter plays with our subconscious fears and suspicions – our imaginations apparently primed to disappear into dark alleyways and crevices of connotation and meaning, at the slightest cues. In these rooms, behind our FILTH masks, we are all Dorian Gray. We are all the products of our culture and its complex history of erasure and reappearance, of suppression and statement. Toxicity and delicacy coalesce in tension and harmony in these mirrors, finely wrought, to expose and free dark things in pastel shades.

.jpg)