Musée D’Art Moderne De La Ville de Paris

18 October 2016 – 12 February 2017

by SAM CORNISH

In 2010, Carl Andre (b1935, Massachusetts) ended a career dedicated in large part to endlessness. He gave up making large sculptures or accepting commissions, limiting his art-making to small-scale works given as gifts to friends. A small display of these provides the coda to the survey exhibition Carl Andre: Sculpture As Place, 1958-2010, now at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Organised in collaboration with the artist and first shown at Dia Beacon in New York in 2014, the exhibition has travelled to Madrid and Berlin and finishes in Los Angeles in 2017.

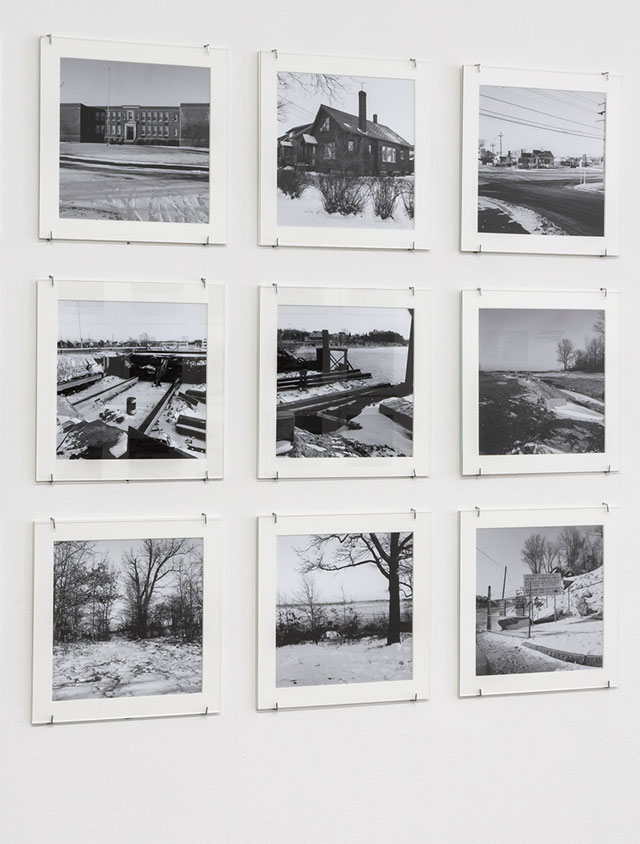

Andre’s output over the previous half-century is one of remarkable consistency and single-mindedness. Those less receptive to his work’s ascetic pleasures might say repetition and bloody-mindedness. The impression of a single-path doggedly followed pervades Sculpture As Place, despite the inclusion of peripheral aspects of Andre’s practice. These include: a selection of his poems, where visual and systematic order takes the place of conventional rhyme and meter; Passport of 1960, an autobiographical miscellany of artists, images and motifs important to the formation of his artistic identity; the Dada Forgeries – occasionally humorous assemblages made throughout his career, but rarely exhibited; a selection of photographs of his hometown of Quincy, Massachusetts, showing scrapyards, and other semi-industrial hinterlands, cliff-faces, pathways through woods, that all suggestively relate to his sculptures.

Where these peripheral strands all contain – or are – images, the mainstream of Andre’s five decades of work comprises sculptures that are devoid of imagery, physical structures that attempt to be solely what they are, with all the viewer’s attention focused on the simple facts of their existence and the way in which these facts order, interrupt and are bound up with the whole situation in which they are encountered.

As Andre explained in a 1978 interview: “I now realise that one cannot purge the human environment from the significance we give it. But I have a theory that abstraction arose in Neolithic times, after Paleolithic representation, for the same reason that we are doing it now. The culture requires significant blankness because the emblems, symbols and signs which were adequate for the former method of organising production are no longer efficient in carrying out the cultural roles that we assign them. You just need some tabula rasa, or a sense that there is a space to add significance. There must be some space that suggests there is a significant exhaustion. When signs occupy every surface, then there is no place for the new signs.”1

The exhibition opens with a selection of small sculptures Andre made in the early 60s, while working on the Pennsylvania railway and with only limited space and resources. These are shown alongside a series of photographs taken by the film-maker Hollis Frampton in the late 50s and early 60s, that document a wider range of similar small, experimental sculptures. Andre did not consider either group complete works in their own right, rather as tests pointing the way to future possibilities. They emphasise the extent to which his art emerged almost fully formed, following the impact of Constantin Brâncuși’s sculpture and the black paintings of Andre’s childhood friend, Frank Stella. Geometric units, simply fashioned and placed rather than joined together, with arrangements based on right-angles and simple stacking, appear here and never leave. Much of Andre’s career is a matter of variations on a basic repertoire that is pretty much completely established by the end of the 60s. Many of the works exhibited in Paris are remakes of originals, made for particular exhibitions or collections. I can imagine devotees of Andre’s sculpture obsessively registering the nuances between different installations of the same sculptures, or between new versions, often realised in different materials, of old sculptures.

The major aspect of Andre’s later work that is only hinted at by the very early experimental sculptures is its horizontality. The first two large-scale works in the exhibition, from the late 50s, are vertical, following the example of Brâncuși’s Endless Column. From then, the exhibition comprises parts spread laterally across the ground, whether in tight or loosely organised fields, or appropriating the forms of fundamental architectural features, such as walls, floors or bridges. This spread outwards is central to how Andre’s work responds to – or at least engages with – the different places in which it is shown. Considering the Paris show as a whole, and looking at some other installations illustrated in the accompanying catalogue, this is perhaps not exactly a matter of responsiveness. It seems, instead, on the one hand, to involve opposition and interruption, and, on the other, demarcation, control and annexation. The tendency is for the total situation to become an Andre, its identity temporarily subordinated to the invader in its midst. In a sense, this applies generally to single artist installations – the work is the main event and the place it is shown is a backdrop. But what distinguishes Andre’s sculpture is the extent to which it allows its surroundings to be seen, while asserting its own identity and independence in and from its environment.

I began by saying that Andre’s career had been dedicated to endlessness. The implication that a pattern or sequence could continue for ever is clearly important to Andre, and bound-up with his commitment to horizontality and his inheritance from Brâncuși. Yet it needs qualification. Despite its tendency to spread out into installation, his work – based on the exhibition in Paris, I would say particularly his best work – contains at least a memory of sculpture considered as a formally coherent, limited structure. “I may be absolutely mad, but I see my work in the line of Bernini, Rodin, Brâncuși, and then I would put my own name at the end of that line.”2

Sometimes, coherence follows from giving the spaces between a sculpture’s units sufficient identity of their own; elsewhere it involved individual units with enough self-presence to truncate a sequence with certainty. Conversely a sculpture such as 44 Carbon Copper Triads seemed endless in a negative sense – without a clearly considered relation between its parts, there seemed no special reason why the sculpture stopped where it did. Perhaps when it was first shown it was displayed in a much more limited setting, providing an external limitation otherwise lacking? I felt that the most convincing, and also most troubling, works in the exhibition were those made from flat plates of metal, which the audience are allowed – in fact here encouraged by the wall labels – to walk across. They seem to bear down on the floor. I could see the weight of the metal. Walking on them, for me at least, referred back to the initial visual experience, which remained primary. The walking confirmed my visual apprehension of their weight and also helped to dissipate the sense that their impact was just a matter of staking out an area – which might have implied they were just empty, plinths lacking sculptures. Rather they appeared definite – clear and dense. Despite my worries that this is all a fuss about almost nothing – or relies on a kind of hyper-attention to experience that is difficult to justify – I found these works difficult to ignore, and they remained with me for sometime after the exhibition.

References

1. Carl Andre quoted in Carl Andre interviewed by Peter Fuller, Art Monthly, 1978, reprinted in Patricia Bickers and Andrew Wilson (eds), Talking Art 1: Art Monthly interviews with artists since 1976, Ridinghouse, 2013.

2. Ibid.