Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

23 February – 29 May 2022

by DAVID TRIGG

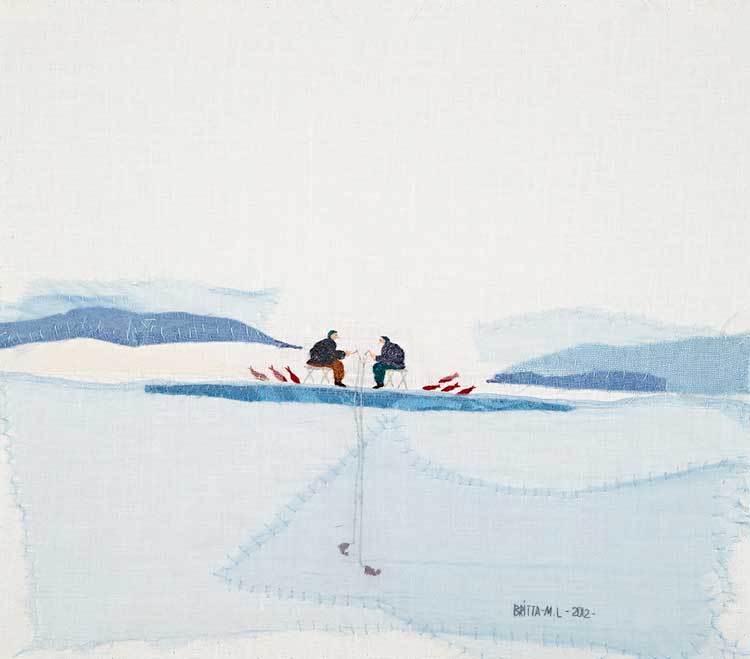

There is something undeniably charming about the miniature stitched worlds of Britta Marakatt-Labba, whose delicately embroidered scenes chronicle the history, culture and cosmology of the Sámi community, one of the largest Indigenous groups of northern Europe. Her wintery landscapes, ranging from scenes of reindeer-herding and ice-fishing to figures frolicking in the snow or huddled together in traditional lávvu tents, have the feel of festive greetings cards. But a closer look at the seemingly benign imagery in this, the artist’s first solo exhibition in the UK, reveals darker themes: exploitation of the land, far-right terrorism and even the Holocaust. Beneath its congenial surface, the artist’s work is no less than an impassioned protest against environmental destruction, extremism and the violence of colonialism.

[image2]

Born in 1951, Marakatt-Labba was raised by reindeer herders in the Scandinavian mountains of Sweden. Embroidery has been her medium of choice since the 1970s and, though she studied at Gothenburg’s Academy of Design and Crafts, her work is rooted in the handicraft tradition of the Sámi, known as duodji, which she learned in childhood. Storytelling is central to her practice, and it is through needle and thread that she has related accounts of Sámi life for more than four decades, using techniques that reference Indigenous textiles as well as historical sources, from the Bayeux Tapestry to late renaissance wall hangings. Combining simple running stitch, appliqué and painted elements, her compositions are striking in their economy, conveying the essential information of a scene with a handful of basic elements.

[image8]

An understanding of history is crucial to grasping Marakatt-Labba’s work. The discovery of silver in Lapland in the 1630s galvanised the Swedish Crown’s expansion into the Sápmi region traditionally inhabited by the Sámi. Not only did it mark the start of resource extraction in the territory – including fur, game and minerals – but also the colonial agenda to “civilise” the Sámi and displace them from the land. As several works in the exhibition reveal, the colonial legacy in Sápmi is still evident today. Take Minerálaroggan/Mineral Extraction (2018), one of several sweeping panoramic landscapes highlighting the threat to Sámi grazing lands. Here, black running stitches outline the site of a proposed mine to extract iron ore, while elsewhere, in Čullon Meahcci/Felled Forest (2020-21), scores of birch trees lie on their sides in reference to the increased logging of the ancient woodlands where herders have grazed their reindeer for generations.

[image3]

Appearing in many of these stitched landscapes are goddesses wearing ládjogahpir – the distinctive curved hat worn by Sámi women that was once prohibited under colonial rule. These spiritual beings signify protection for the Indigenous populations as their ancient way of life repeatedly collides with corporate interests and the effects of climate change. The broad history of Sámi culture is recounted in the epic 24 metre-long tapestry Histoja/History (2003), which brought Marakatt-Labba to the attention of the wider art world when it was shown in Documenta 14, in Kassel Germany in 2017. The tableau, which hangs in Norway’s University of Tromsø, is presented in Birmingham on video and includes episodes such as the Kautokeino uprising of 1852, in which a group of pious yet militant Sámi killed representatives of the Norwegian authorities while protesting against the state church’s ties to the alcohol industry. The event led to the ringleaders being executed and sparked a long period of repression and forced assimilation of the Sámi.

[image4]

Modern confrontations with Norway’s authorities are addressed by the powerful allegorical embroidery Garjját/The Crows (1981/2021). Relating to peaceful protests against a proposed hydroelectric dam on the Áltá River in the late 1970s, this fantastical image shows an intimidating flock of crows flying over activists’ heads, which upon landing transform into aggressive police officers. Marakatt-Labba was one of the arrested protesters and even spent time behind bars. A symbol of authority in Sámi culture, the crow is a creature that grabs what it can. In the adjacent work, Girdi Noaiddit/Flying Shamans (2011-21), it is the police who have been grabbed, this time by soaring shamans, who drop them like rats into the river below. If, as some have suggested, Garjját is a history painting, albeit one grounded in duodji practices and materials, then its humorous counterpart might be considered a Capriccio.

[image5]

Among the most atypical works in Marakatt-Labba’s oeuvre, Dáhpáhusat Áiggis/Events in Time (2013) is also her most haunting. Several large burlap flour sacks dating from the Nazi occupation of northern Europe hang in a broken circle, evoking a Sámi lávvu tent. There are allusions here to the Nazi’s intention to eradicate the Sámi, who were considered ethnically inferior to the Germanic “Nordic” Norwegians. But the grubby sacks, stamped with Third Reich insignia, also provide the canvas for a stark, semi-abstract portrayal of the 2011 Utøya terror attack. Here, the right-wing extremist Anders Behring Breivik, whose murderous rampage on a Norwegian island left 69 dead, including several Sámi youths, is reimagined as a double-headed eagle, surrounded by weapons firing bullets. In combining these two historical events separated by seven decades, Marakatt-Labba teases out the dark connection that unites them: the pernicious ideology of the far right.

[image6]

Although the Sámi language does not have a word for “war”, these nomadic people are no strangers to conflict. Their desire for a peaceful existence with the natural world is constantly threatened by a culture that sees nature as a resource to be plundered and exploited for profit. This is the tension at the heart of this exhibition: the struggle between tradition and progress, between nature and technology, between the timeless landscape and rampant industrialisation. These might be themes that have preoccupied artists for centuries, but for Marakatt-Labba it is the imminence of these issues that makes her work so urgent, so timely.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-1.jpg)

-16.jpg)

-2.jpg)

-3.jpg)

-4.jpg)

-5.jpg)