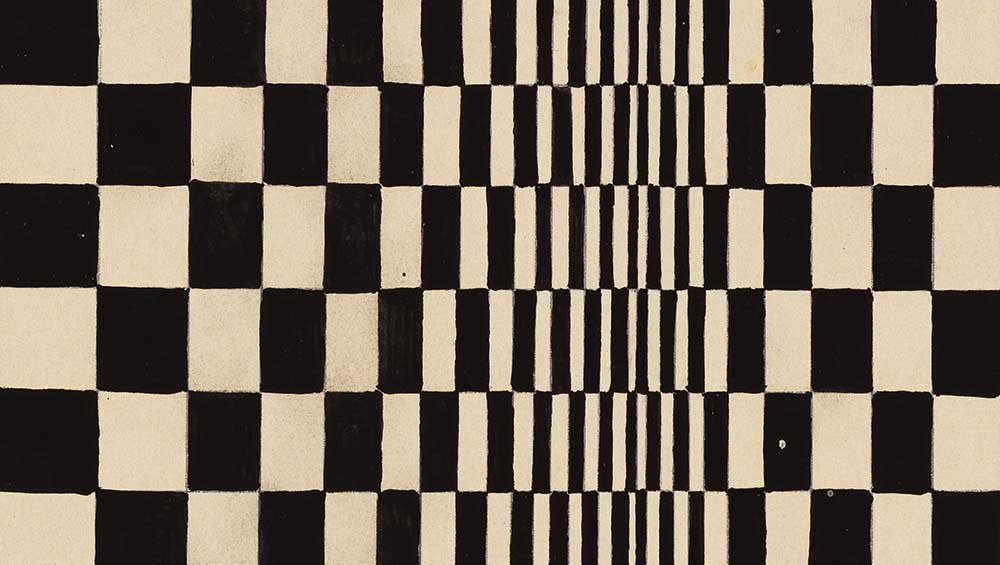

Bridget Riley, Study for Movement in Squares, 1961 (detail). Gouache on card. 6 1⁄2 × 6 3⁄4 in (16.5 × 17.2 cm). Collection of the artist, © Bridget Riley.

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

4 February – 28 May 2023

by JILL SPALDING

None who attended Bridget Riley’s first solo show, in 1962 at London’s Gallery One, has forgotten it, a revolution in perception as unsettling as snow in the south. The impact of her optics was jolting – at once intellectual and emotional, disrupting and exhilarating – and I remember fearing that, if I didn’t move out of the field of those vibrating geometrics, the dazzle would topple me.

Even as Riley’s vision was “vulgarised” (as she still sees it) by fashion and furnishings – all those fabrics and housewares awash with polychrome dots and skewed stripes – the ideas transferred from her studies on to large canvases, with a precision enabled by a tailored formula of emulsified paint, were so elaborately thought out as to elude meaningful replication. Animating the space with canny manipulations of line, shape and contrasting tonalities, they derived their power from repeating patterns conceived to dislocate and recalibrate. Luminous and monumental, their effect on the retina seemed miraculous – the magic, not of a party trick, but of a new way of seeing.

This by way of explanation as to why I didn’t expect much from the drawings, albeit billed as the most comprehensive showing ever staged by an American museum and, for the most part, sourced largely from Riley’s studio and from private collections, most never seen before. I am still eating my hat.

Approach Riley’s drawings with her dictum of “receptive participation” and you will discover that such is her mastery of kinetics and craft that even the small renderings, and even those lacking the immaculate finish created for her paintings, deliver the same punch.

Bridget Riley. October 24 revision B, 1986. Gouache on paper, 26 3/4 x 25 3/8 in. Collection of the artist, © Bridget Riley.

Organised chronologically, the exhibition mounts the early works in a separate gallery. Don’t miss them. “How artists start is quite important,” Riley has said. The only painting included, Blue Landscape (1959), a hybrid study of Cezanne’s flat-planed Provence and Georges Seurat’s pointillism,speaks to a grounding in art history and (together with her scaled-down copy of A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte that hangs on her studio wall) to her deepening investigation into the refraction of light and the power of the dot.

See, too, how the early black pastel and crayon landscapes taught her to manipulate space and shading, and how the chalk and charcoal tonal studies of the human body, undertaken to analyse movement, brought her to eliminate texture, inflection and any hint of a blurred edge. Most revealing is Self-Portrait (1956), a biomorphic construction built of monochrome geometric shapes with the more yielding Conté crayon to create a “light-to-dark tonal scale – long thought her entry to abstraction”. (The artist later flagged the eureka moment as the “flash of light” produced in Kiss, 1961, by the white line bisecting a black-on-black juxtaposition of Ellsworth Kelly-like shapes. Revealing line to be a fundamental form occasioned the theory she would develop into an extensive “visual vocabulary”, much as Seurat had deployed the dot.) Riley’s figurative drawings had been accomplished enough to provide a comfortable living, so her leap to abstraction was largely intellectual, delivering the freedom to “objectify tonality” and to explore with string compass the sensations created by an intricate interplay of geometrical forms.

Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 4 February – 28 May 2023. Photo: Jeff McLane.

The year 1964 marks her career breakthrough. Whereas the earlier showing in London had launched her, Riley’s lasting fame traces to the black-and-white abstractions shown that year at the Yale Center of the Arts and to the Museum of Modern Art’s acquisition of Current, featured on the catalogue cover of its 1965 exhibition, The Responsive Eye, staged to showcase Europe’s newly heralded op artists.

Revolution is not too strong a word for the impact of Riley’s involute dazzle on the collective brain that for ever set her apart from her imagist Royal College of Art colleagues (David Hockney, Allen Jones, Patrick Caulfield, Richard Smith). Not that she was the first to upend the western canon’s three-dimensional perspective. In 1960, Los Angeles had brought London’s ICA such fledgling hard-edge artists (a term coined for the show) as Frederick Hammersley and John McLaughlin, and Kelly had already made his mark, but Riley’s deeper investigations into op art’s possibilities completely upended the understanding of perception as what you see with a uniquely multidimensional vocabulary of how you see it – a vision of “perception is the medium through which states of being are directly experienced” that won her the international prize for painting at the 1968 Venice Biennale (the first woman to receive it) and that, newly adopted by Gen Z, visionary artists such as Uta Barth, and non-fungible token engineers, is once again rocking the world.

Take a deep breath before transitioning to the main gallery. Like a volley of fireworks, it opens with a stunning selection of the pulsing black-and-white geometrics that established her signature. Leading off with Studyfor Kiss, they showcase her mastery of the hidden image (Hidden Squares, 1961), of oscillation (Blaze, 1962), and disturbance (Zig-Zag, 1963). All manifest a fluidity that belies extreme effort (once, Riley spent three weeks on achieving a particular curve). These, for me, are the show’s heart and soul. Most directly, for their hand-wrought immediacy. Whereas the paintings, transcribed by assistants, derive their primary power from retinal wizardry, the intimacy of the preparatory studies, although impeccably executed – no wayward lines or rough edges – impacts viscerally. Most lastingly, for the beauty of the radiating forms and their starkly contrasting black-and-white interaction. Outsized chequerboards melt together as they seem to recede; horizontal stripes are reduced and expanded, darkened and lightened, to take on a newly radical “pictorial identity”; intersecting squares and circles morph into vibrating hybrids. Now fully commanding space and volume, Riley orchestrates triangles, spirals and ovals into elaborate compositions arranged to surprise and derail. Stand close and the pattern is constant; move away and the optics will make your legs buckle.

Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 4 February – 28 May 2023. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Having plumbed the potential of stark black and white, Riley experimented with the more subtle tonalities of grey – pencilled grids, shaded ovals – quickly exhausting its limitations. Often a search reached a dead end; shown here, the lacklustre lava-black square resulting from her failed experiment with solid fields.

The late 70s opened Riley’s palate to colour with her keystone revelation of line as a fundamental form. Staunchly positing “line as colour” (a founding principle that eludes me), she created “what you might call a colour vocabulary” – vibrating fields achieved with noncomplementary colours – to produce the body of work that predominates here. Pairing varying saturations of such as red, green and turquoise complicated the rippling effect devised to engage the spectator in a visual discourse of how to see. The wave drawings deliver; standing in front of the two-toned pencil and gouache Twisted Curve unsettles but invites participation. Not so the serial renditions of horizontal stripes, selectively coloured to shimmer but appearing, to my eye, mechanical. Even the intricate piecing of later works cut into interlocking shapes in the manner of a Matisse collage fail to disrupt.

True, all convey serious analysis. Like all Riley’s studies of visual agitation, each was undertaken to distinguish optics from tricks; “that some elements … can be interpreted in terms of perspective or trompe l’oeil is purely fortuitous and is no more relevant to my intentions than the blueness of the sky is relevant to a blue mark in an abstract-expressionist painting.” And all are of interest as studies for the prints or as worksheets for the execution of large paintings. Colour does contribute to animating the wave drawings and several are masterful. Yet, for me, they remain lesser, speaking more to craft than to glory, while the black-and-white studies fully illustrate Riley’s oscillatory wizardry, her unique control of geometric forms and her ability to create an “event” where the “spectator experiences at one and the same time something known and something unknown”.

Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 4 February – 28 May 2023. Photo: Jeff McLane.

All, however, are valuable as keys to her process and speak to her rigorous exploration, over 74 years, of form and motion. That each juxtaposition of line, shape and colour was conceived to create a neurological and psychological disturbance is why Riley’s complex geometrics cannot be figured out, only experienced.

Giving op art lasting significance, these exercises in perception are not puns, puzzles, tests, charts, mathematical equations, or games. Riley’s elaborate disruptions humanise optics, rather than codify them, because they skew perception organically. Linking them to the output of Victor Vasarely, who encouraged the transposition of his geometrics to textiles and murals, completely missed the point.

Avoiding that pitfall, Riley remains one of the very few artists whose commentary on her own work renders the critic inessential. Case in point is her observation about polarities as “an echo in the depths of our psychic being … static and active, or fast and slow. Repetition, contrast, calculated reversal and counterpoint also parallel the basis of our emotional structure.”

Also, “I want the disturbance or ‘event’ to arise naturally, in visual terms, out of the inherent energies and characteristics of the elements which I use.” And, “The basis of my paintings is this: that in each of them a particular situation is stated. Certain elements within that situation remain constant. Others precipitate the destruction of themselves by themselves. Recurrently, as a result of the cyclic movement of repose, disturbance and repose, the original situation is restated.” Nothing more need be said.

But more must be recognised. “Ubiquitous as Henry Moore”, observed by a contemporary, has widened to an appreciation of Riley’s enduring imprint on perception. Yes, find it in socks and frocks, but experience it, too, as you feel a tingle looking out on a dancing fence or a shimmering landscape, and it will stir life into the drab of your day.

• Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio will travel to the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, from 23 June to 8 October 2023.