by ANNA McNAY

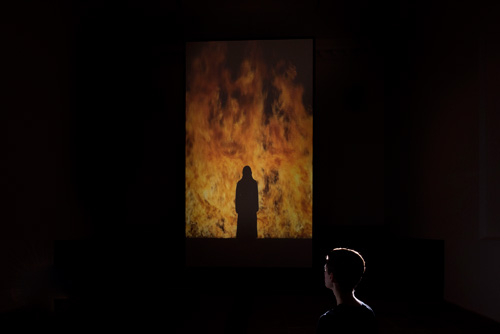

Bill Viola (b1951) was an early pioneer in the medium of video art and his work has been shown not only in museums but also in universities and religious institutions across the globe. His universal themes of life and death speak to audiences from all walks of life and the expressions of his actors evoke powerful, empathic responses. His works take inspiration from the history of world art and religions, and Viola is well versed in Buddhism, having spent a year and a half living in Japan, studying with a Zen master. His emotionally charged, slow-motion works are inspired by traditions within Renaissance devotional painting and certainly exhibit a painterly quality, while other pieces, such as The Veiling (1995), projected through layers of translucent cloth, hung as screens across the gallery, are more sculptural in form. A current exhibition at Yorkshire Sculpture Park brings together 10 of Viola’s works from the past two decades, including a new work, The Trial (2015). It is his most extensive show in the UK for more than a decade.

Viola spoke to Studio International at the opening of this exhibition.

Anna McNay: Your work deals with some of the central themes of human consciousness and experience – birth, death, love, emotion and spirituality. How has it evolved over the years? Would you say your themes and interests have remained consistent? Has your viewpoint developed as you’ve garnered more personal experience, both of life and of art-making?

Bill Viola: I first used the camera and lens as a surrogate eye, to bring things closer, or to magnify them, to experiment with perception, to extend vision and make lengthy observations of simple objects. Once you do that, their essence becomes visible. So I suppose I was always interested in the inner life of the world around me.

AMc: Have you been influenced by changing technologies? You’ve spoken of the absence of solitude filling our minds with useless information. How do you protect yourself from this overload? Many artists – for example, David Hockney and Derek Boshier – have embraced the iPad and use it as a tool. I assume you are not about to follow in their footsteps?

BV: No, I am not interested in the iPad as a tool for my own art, but why not? Beautiful creations have been made with a twig and pigment. The development of the technologies of the moving image has been important for me as it broadened my palette and stimulated new work. When flat-panel screens were invented, for example, I felt liberated from the box of a TV screen, and also from the projector. I explored human emotions in the form of portraits – portraits that I could hang on the wall, or place on a shelf. What comes with today’s overwhelming glut of the moving image is that we cannot escape it. Now it is on billboards as you drive on the freeway.

AMc: You began reading about different world faiths while studying fine arts at Syracuse University in New York in the 70s. Were you brought up in a particular faith? And do you follow one now?

BV: My mother was Episcopalian and even though I went to Sunday school, I was not really brought up in a strongly Christian home. I do not follow any particular faith, but like to meditate and believe in peace and compassion.

AMc: You fell into a lake when you were six years old. What did you learn from this experience? Does it still feed into your work today?

BV: I saw the most beautiful watery world and did not want to leave. I did not realise it at first, but I think this experience was seminal in creating pieces like Five Angels for the Millennium (2001) and Ascension (2000).

AMc: Of the four elements – fire, water, air and earth – it seems you work primarily with the first two. Do they hold more significance for you? If so, in what way?

BV: I have worked with fire and water for a long time. The two seem to be opposites, but in fact are quite similar. Both can represent destruction or purification, life or liberation. Both are fluid and fascinating: they can be gentle and life-giving, or terrifying and violent. We only began working with air and earth for the work in St Paul’s Cathedral, London, Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water) (2014) and it was not easy to develop the right action for air and earth. We had to strip everything down to the barest essentials and made each element a protagonist.

AMc: You have said of The Dreamers (2013) that they represent eternal life. When you first look at them, they are beautiful, but then you realise the subjects aren’t breathing. To me, therefore, I see death. Is death simply a disguise for eternal life?

BV: Water is the sustainer of life, it is the amniotic fluid, it is the place in between, where the dreamers neither take a breath nor come to the surface. Nor do they open their eyes.

AMc: Your exhibition at Yorkshire Sculpture Park is superb but, at the same time, I almost found it too much. I could happily sit for an hour or so with a single one of your works and the impact from it would stay with me for months. How did you go about selecting which works to include and how to position them in relation to one another? There is just one way in and one way out of each room, so visitors are forced to take a specific journey through the show. Do you think the works form a cohesive whole? Is each one seen differently, as part of this whole, than it might be, seen alone?

BV: These are all good answers to your questions. Yes, we always create a journey. Once the viewer is on the path, they don’t surface until the end, it is immersive. Our team, Kira Perov, Bobby Jablonski and myself, created an interior space that is filled with people, in contrast to the outside, which is all nature, trees, hills, sheep. The people inside represent our inner world, our emotional world and our spiritual world.

AMc: Your work is being shown at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Do you see it as a form of sculpture? I felt this dynamic in particular with The Veiling (1995), where the image is projected through layers of translucent cloth, hung as screens across the darkened gallery, with a projector on each side, enabling the visitor to walk around – and almost through – the work. Here it becomes tangibly 3D. But elsewhere, too, there is a sense of the subjects stepping out of the frame and into the darkened gallery – for example, at the end of Night Vigil (2005/2009).

BV: Yes, thank you for those comments. Sound and movement and light and veils – it is all a physical experience.

AMc: For me, your most powerful works are those that focus on changing expressions. My favourite series – not on show at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park – is The Quintet Series (2000). The Return (2007) (which is on show) has a similar impact when the woman steps through the wall of water and her expression contorts with agonising grief. How much scripting or directing takes place for a work like this and how much is left down to the actor? Have you ever had someone come to be filmed, who simply couldn’t produce what you wanted?

BV: I spend some time getting to know the performer and we talk about deep personal experiences, which puts them into the right emotional zone. Weba Garretson, the woman in The Return, has worked with us for many years, since the Passions series. We have a good understanding. She had recently lost her mother and this “purification” with the water wall helped her through some of her grief. We try to choose people who will be good collaborators with the idea, but sometimes they do not work out, so we simply do not use their takes.

AMc: You mentioned over lunch at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park that you don’t tell your actors quite what to expect – so as not to dampen the impact of shock or influence their expressions. In The Trial, your two actors are drenched from above with black, red and white fluids and then warm water. What exactly might these actors have been told in their briefing to prepare them for this? Presumably, they will be familiar with your work anyhow and thus expecting something along these lines?

BV: The performers were told about the fluids and the order in which they would be coming. There were emotions and feelings attached to each of the colours, but that gave way in the end to whatever the performers were experiencing. We knew that we needed to get the first take in each instance, since we needed the element of surprise and that cannot be duplicated. We had not worked with these two people before and I don’t think they knew much about the work.

AMc: The exhibition coincides with the release of a fantastic Thames & Hudson monograph on your work. This book – and the smaller exhibition guide to accompany the exhibition – are edited by Kira Perov, your wife and executive producer and director. How involved is she in your work on a daily basis? How difficult is it to differentiate between work and home life?

BV: Kira has worked with me since 1979. Over the years she has taken on more and more in terms of the production and editing of the works. She organises and coordinates exhibitions of the works worldwide and is responsible for our paper, photo and videotape archives. I could not do what I do without her.

AMc: The monograph includes a lot of reproductions of your sketches and preparatory drawings, technical diagrams and notes. Are you not worried that, like a magician, revealing how things are done – for example, the mind-boggling levitation in Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain under a Waterfall) (2005) – might spoil the illusion and impact on the viewer?

BV: I am happy that my creative process has been documented and recorded, thanks to Kira. I don’t work with tricks, so it is always good to share some of the behind-the-scenes stories. What is in this book is only a fraction of what is there, many more pieces and more drawings and notebooks.

AMc: You wrote a note when you were 33 saying: “Once we have procreated, the next transition is death, but somewhere in between these two posts we look for something else – we know there must be something that lies deeper …” Do you know yet what that something is?

BV: I am still searching…

• Bill Viola at Yorkshire Sculpture Park runs until 10 April 2016. Bill Viola: Moving Stillness (Mt Rainier), 1979, is showing at Blain Southern, London, until 21 November 2015.

Bill Viola by John G Hanhardt, edited by Kira Perov, is published by Thames & Hudson, price £40.

-Kira-P-erov,-courtesy-Bill-Viola-Studio-.jpg)

-Kira-Pe-rov,-courtesy-Bill-Viola-Studio-2-.jpg)

-Kira-Pe-rov,-courtesy-Bill-Viola-Studio-3-.jpg)

-Kira-Pe-rov,-courtesy-Bill-Viola-Studio-4-.jpg)