by ALLIE BISWAS

The industrial origins of a striking white building close to the centre of Turin can immediately be sensed if not seen. The streamlined white contours of the Merz Foundation, established in remembrance of arte povera artist Mario Merz in 2005, formerly housed part of the Lancia car factory, and reflect the modernist architecture of 1930s Italy. Walking up the short driveway to the entrance, a vertical row of red neon numbers can be seen up the side of a tower. On closer inspection, the lit-up digits read “1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8”. Merz was fascinated by the number system named after the medieval Italian mathematician Fibonacci, whereby the next number in the sequence is found by adding up the two numbers before it.

[image6]

Although the foundation was established to honour Mario’s name, his wife – and, arguably, the more interesting artist – Marisa Merz, has also been celebrated by the foundation as part of its exhibitions programme. Marisa, who died last month at the age of 93, was a prodigious talent and the only female artist to be identified as part of the Turin-based arte povera group. Her experiments with abstracted themes of nature and metaphysics were recognised only towards the end of her life: the first retrospective of the artist’s work in the US took place in 2017, accompanied by an inaugural English-language monograph.

[image7]

Located in the burgeoning Borgo San Paolo neighbourhood, the foundation is a short walk from the Gallery of Modern Art and the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, and only an hour from Milan. Drawing an international crowd, Turin has built on its rich art-historical foundations, becoming an important contributor to present-day dialogues. The Merz Prize was established by the foundation in 2015 with the aim of identifying emerging talent in the fields of art and contemporary music. Names are nominated by an extensive network of artworld figures; members of this year’s jury for its third award include the artist Lawrence Weiner and Massimiliano Gioni, artistic director at the New Museum, New York.

Bertille Bak, a French video artist, is a highlight among of a group of art category finalists that includes Mircea Cantor, David Maljković, Maria Papadimitriou and Unknown Friend. The works of all five are currently on display in an exhibition at the foundation.

Bak (b1983, Arras) studied with Christian Boltanski and has spent the past decade developing an intelligent and compelling practice that centres around fictional and ethnographic documentaries. Bak focuses on communities that have been overlooked or discriminated against, and is interested in how people participate in their own environment, as well as their relationship with wider society. The artist joins the people she documents, living with them for several months to learn about their culture as well as their circumstances. She has examined a diverse range of subjects to date, from residents in the mining towns of northern France to a small Bangkok community under threat from the development of a shopping mall.

A solo exhibition of Bak’s video works is on display at Le Cyclop, Milly-la-Forêt, France, until 20 October.

Allie Biswas: Tell me about the works you are presenting at the Merz Foundation.

Bertille Bak: The project is about circulation, the mapping of territories, and new archives that are filled with stereotypes about the Roma population.

Transports à Dos d’Hommes (Transport on the backs of men) is a video that features the inhabitants of a Romany slum in the suburbs of Paris. It is a kind of collective fable that describes the present situation as well as the future of a group that is in permanent fear of expulsion. In this absurd narrative, public transport systems join forces with the French government to silence this population. The noise of helicopters drowns out Roma voices, subways swallow musicians’ notes and trams are called on to displace the inhabitants.

[image5]

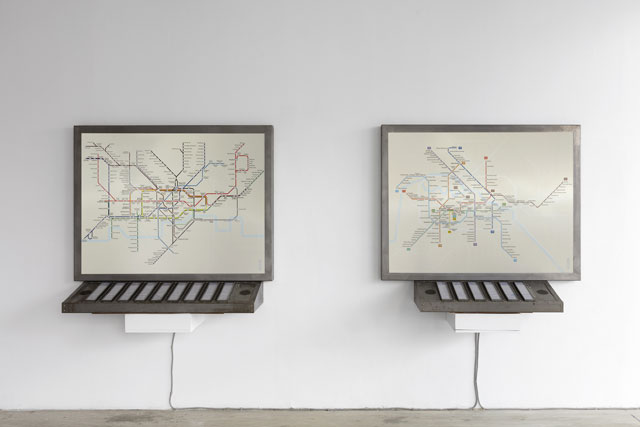

Interactive maps of London, Rome and Berlin called Notes Englouties (Swallowed Sounds) are near the video projection space. They play on-demand sounds from the metro lines of all three cities, which have been methodically archived. This archiving allows us to identify the noisiest stations and the most hostile environments for musicians to play in.

In the context of a busy city, where the transport militia construct lies, the red traffic lights that appear in the last project, titled Itinerario Bis (Alternative Route), undermine the city’s Roma population. In this work, I refer to a new law in Italy, which reduces the waiting time at traffic lights throughout the country so that motorists are no longer bothered by window washers from eastern Europe. With each silence in the soundtrack, flags (made from curtains recovered from the slum) are activated intermittently.

AB: The flags are positioned near to the ceiling, and on the opposite wall is a series of postcards.

BB: Thirty-four paintings are reproduced on these postcards, which depict every red traffic light found between the Merz Foundation and Torino’s police headquarters. It’s a kind of symbolic march from the peace flags that hang in the exhibition space to the official building where three flags also adorn the facade. The offerings in the exhibition space map all of the real or symbolic barriers that prevent integration in the city.

[image2]

AB: Although the display shows you working in a variety of media, you have developed your career primarily as a video or film-maker.

BB: I do not think I fall into the category of film-maker, perhaps because the term for me suggests scripted writing, pristine plans and the absence of clumsiness, whereas the videos presented here are closer to a joyful DIY project with “budget” special effects. What are important to me are the encounters and collective action; ephemerality and making without constraint.

AB: The way you work reflects this DIY approach.

BB: Only one camera is used for shooting, and there isn’t any film crew or other sound technicians; the team that makes the images is formed within the group that met.

In my early years, in a fine-arts setting, the medium of video became the perfect ally for making short films with all the members of my family, and then with all the inhabitants of the city of my grandparents. It quickly appeared to me as a “sharing” medium that everyone could seize, in order to take part in the construction of a story.

[image3]

AB: How do you decide which community you are going to immerse yourself in, and where does this commitment to others come from? Is your intention to bring wider awareness about certain groups of people?

BB: It is mainly the place I am in that leads me to discover those who occupy it – a mining town where my family lives, a Paris subway that leads me to Roma musicians, a chapel to the Elders, a residence in a port city that brings me in proximity to sailors or shellers of small grey shrimp in Morocco. It is true that I am interested in groups living in situations of injustice that have been overlooked, or marginalised communities, but, above all, I observe the intricacies of my immediate environment.

The fallout from such a common creation will be in vain. This departure will not solve the problems in which these communities are mired because the rebellion presented here is ultimately a fiction and a fraud with no revolutionary value. It’s not so much about allowing people to learn more about themselves, although there is probably a new perception of themselves that arises. Perhaps the priority is not to let their spirit of rebelliousness escape. And it is through highlighting these anonymous lives, through these simple “various facts” that the viewer can then perceive the derivatives of modern times.

AB: Your process suggests that you are trying to make yourself at one with your subject. You move into the community you film, living with them, becoming a part of their world.

BB: I have been working collaboratively for years, because videos are always a condensed version of each voice and each life encountered. The long exchange is absolutely essential: it takes six to 18 months to fully involve people in the work’s creation and to be as fair as possible, and respectful of the social and cultural context. But, at the end, it raises a lot of questions for me because I remain the conductor of the work. I do the editing alone, for example, and have to make decisions about the construction of the story. The question of the collective is not simple, my own approach is full of doubts about transmitting the exact words of the groups I work with.

What is common to all projects is that I never arrive in a group with a pre-conceived idea or scenario. I am not a group puppeteer, and the content springs from the various contributions of people. But I think I want to get closer to a certain truth, even though the stories are intentionally fictional. My position as an observer, similar to an ethnologist, allows me to gather as much information as possible and then draw on this reserve of wealth, hobbies, traditions and codes within the group in order to say otherwise, who they are and what they are experiencing. Allowing myself to invent alternative and poetic rebellions to symbolically counter unacceptable decisions and champion anonymous lives is the basis of my practice.

AB: How do you think the term “documentary” relates to your work?

BB: During the months of living with people I meet, I sometimes take some shots of their “real life”. If these so-called documentary scenes can join the construction of the narrative, they are not used as such. Sometimes, these moments are replayed so that the group has full awareness of what it shows. It is not a documentary: the basis of the reality is parodied, amplified, deconstructed or totally transmuted in reverse copy.

AB: You studied with Christian Boltanski. Did that experience help to shape how you developed as an artist?

BB: The memory work of Christian Boltanski has influenced me since my youth. Knowing how to tell stories, and especially being able to step aside, paradoxically, in order to tell the truth, has become the basis of my work. Through it, I discovered that the world of art is a territory capable of giving space to artists who care about humanity and its condition.

AB: What have your collaborations taught you?

BB: These collaborations provide me with the opportunity to live several lives, where living together with the community is a creative driving force. These collaborations remind me of the difficulty of putting down roots in a territory, of maintaining an identity and links.

Finally, these collaborations have taught me that it is not possible to predetermine a specific timeline of creation. For people spending the majority of their lives in a volatile environment, these artistic concerns are not a priority. Working with humans requires time; it can take several years, depending on the groups encountered and situations experienced.

AB: How does it feel to have been nominated for this year’s Merz Prize?

BB: Being nominated for the Merz Prize came as a surprise. The prize is accompanied by the legacy of an iconic and internationally recognised artist, whose work oscillates between fragility and superpower. And the jewel that is the foundation is an incredible setting within which to think up some creative madness, as it were.

• The Mario Merz Prize (3rd Edition) exhibition runs at Fondazione Merz, Turin, Italy, until 6 October 2019; A solo exhibition of Bak’s video works is on display at Le Cyclop, Milly-la-Forêt, France, until 20 October.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)