by JANET McKENZIE

Berenice Carrington lives in Shetland, an archipelago that lies between Scotland and the Faroe Isles, and is a 12-hour ferry journey from Aberdeen. Carrington was born in England in 1962 but, at the age of 14, migrated with her family to Australia. She returned to London to attend Chelsea School of Art, then worked in several Australian states with Aboriginal groups. She completed her doctorate in anthropology, Pekina an Ethnography of Memory, at the Australian National University in 1997. After working on projects in Shetland she moved there permanently in 2013. Her art projects there investigate the meaning of the land and the interaction that humans have with it. She describes her work as ethnographic drawing. We meet in Glasgow.

Janet McKenzie: You describe your work as ethnographic drawing. How would you describe the manner in which you have arrived at the unusual and distinctive genre?

Berenice Carrington: It came about through experience. In Australia, as well as being an artist, I worked as an anthropologist for the National Parks and Wildlife Service in New South Wales. This role influenced my approach to drawing. To carry out a major research project into wellbeing and Aboriginal cultural heritage, I joined forces with Pamela Young, one of the service’s Discovery Rangers. Pamela was a member of the “stolen generation”, a term Aboriginal people coined to explain the negative effects of being removed from their biological families as children, to be raised by non-indigenous families.

[image10]

She and I travelled extensively together in New South Wales, talking with members of Aboriginal communities about their experiences of recording their oral histories and their subsequent transcription and publication. Many of the people who spoke with us were hurt by historical and contemporary government policies. It was a demanding and exhausting experience. In my down time, I started drawing small doodles. Often, I’d be in a hotel somewhere, just knackered and unsettled from the day’s work. The process of making these compositions served as a kind of acclimatisation.

The doodles then carried over into my studio time and they became bigger. Without a conscious effort, I had until that point kept my work as an anthropologist separate from my art practice.

[image4]

To do ethnographic fieldwork, you have to really be there, really open yourself up in order to take everything in. At the same time, paradoxically, you are outside yourself, watching, observing the action from a distance. You distribute your awareness between the inside and the outside of the situation, joining in as one of the group of people you are with and also putting your mind to some other place, that is silent, so as to achieve the observational work. Well, that was the sensation that I recognised while I was doing the doodles. I realised I was no longer making art in a manner that was quarantined from my ethnographic training.

JMcK: Shetland is extremely remote and, in terms of the range of daylight hours through the year, life there could not be more different from Australia. Yet both places are linked by their geographic isolation from cities and from urban life. What is it about marginalised culture that sustains you as an artist?

BC: There isn’t a centre and a periphery anywhere for me. Where you are is a place in its own right. But outback Australia and Shetland are places with low population densities and that is what I notice most. When there is distinct space between people, the influence of commerce and crowds becomes diluted. Correspondingly, the consequences of many human actions can become more conspicuous. I’m intrigued by forms of self-reliance and, when I’m in a place that is socially less populous, there seems to be more room for personal initiative. Australia is not as far away from Shetland as you might think.

[image6]

JMcK: You migrated to Australia at the age of 14 with your family, but returned to London to study at the Chelsea School of Art (as it was known then). What influenced your decision to do that?

BC: I read Mary Quant’s autobiography when I was 15, and her description of dressing up and heading off to the Chelsea Arts Club ball entranced me. At that age, for me, costumes were everything! I set my sights on going to Chelsea School of Art so I could be in this fabulous world that I had read about. I had completely missed the fact that the Chelsea Arts Club and the Chelsea School of Art were different institutions. I did get into Chelsea and secretly waited for the ball to be announced – I was too shy to ask anybody about it – and then I just got on with making sculpture in a much plainer world than that of Mary Quant’s.

JMcK: Who were your teachers at Chelsea School of Art? Was there a stronger emphasis on perceptual drawing there than in Australian art schools at the time?

BC: Shelagh Cluett and Richard Deacon made the biggest impression on me. They were both insightful about the struggle that you go through when first making your own work. At Chelsea, there was no perceptual drawing focus while I was there. It did not impact on me particularly, as I considered myself to be a sculptor.

[image7]

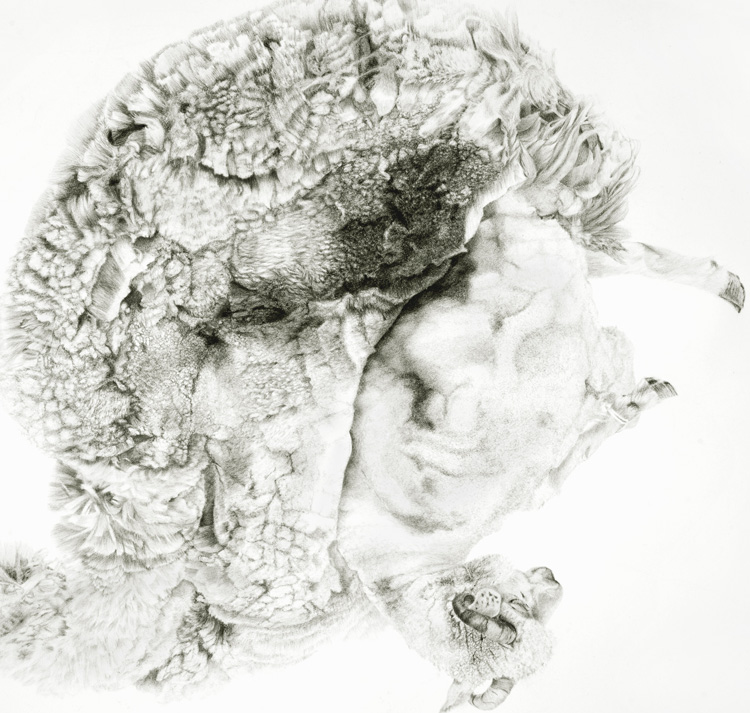

JMcK: You have a distinctive naturalistic drawing style and your drawings are highly evocative. Can you describe the impact your intentions as an artist in anthropological and ethnographic projects has had on the work you do in formal terms?

BC: I think of the naturalistic style of my drawing as empathetic realism. The drawings are meant to offer up ordinary things and situations for contemplation. The realistic style of rendering, with its familiarity, helps people to recognise their world first, and then perhaps to consider the effect of seeing things from that world as drawn images.

The effect that I am after is phenomenological, to allow people to experience the ordinary as otherworldly. The question that drives me is what happens to something when it becomes ordinary and what do we have to do to ourselves for it to be accepted as ordinary? The drawings are meant to release us from those orderly parameters that make things and situations commonplace, so that we can become open perceptually to them.

[image8]

JMcK: What have Australian artists learned from the rebirth of Australian culture, a unique living, visual culture worldwide?

BC: Aboriginal self-determination and multiculturalism were the two big social movements that redefined my experience of life in Australia. The waves of resistance to colonialist policies from generations of Aboriginal people and from migrants to Australia have, in my opinion, established and legitimised public debate about what it means to live there. Australians are confident about art that emanates from ideas that work within the frameworks of anthropology, ethnography and incoming cultures.

JMcK: What can you bring to an understanding of the land and the environment now that you are working in Britain?

BC: The idea of indigenous forms of knowledge versus contemporary thinking in agriculture is something that has really influenced my understanding of how some crofters live on, and work with, their land.

In Shetland, for example, evidence of domestic handworked peat banks in the hill can be interpreted as degradation of a blanket bog, whereas in Australia, it might also be regarded as an indigenous form of land use, integral to the meaning of the landscape and an important component of the management of that land for the future. A paper from the International Union for Conservation of Nature suggested that, in Shetland, Neolithic, bronze and iron age societies most likely used peat as a source of fuel. The continuity of land use is significant.

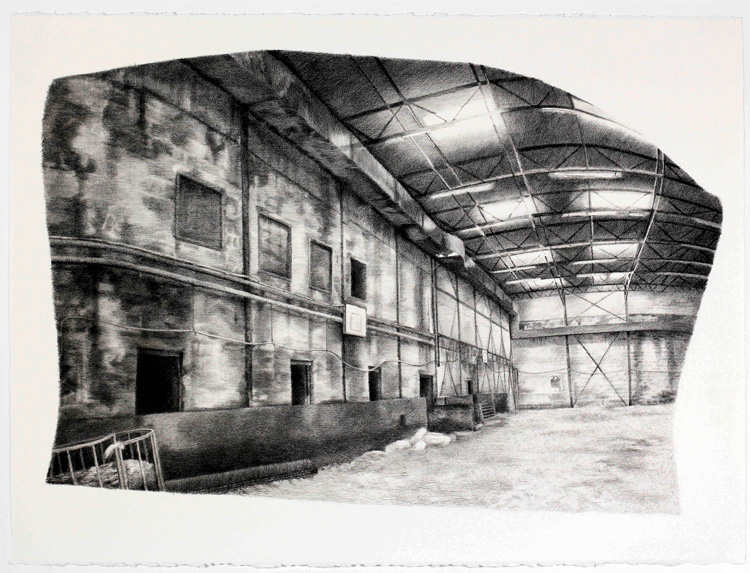

[image9]

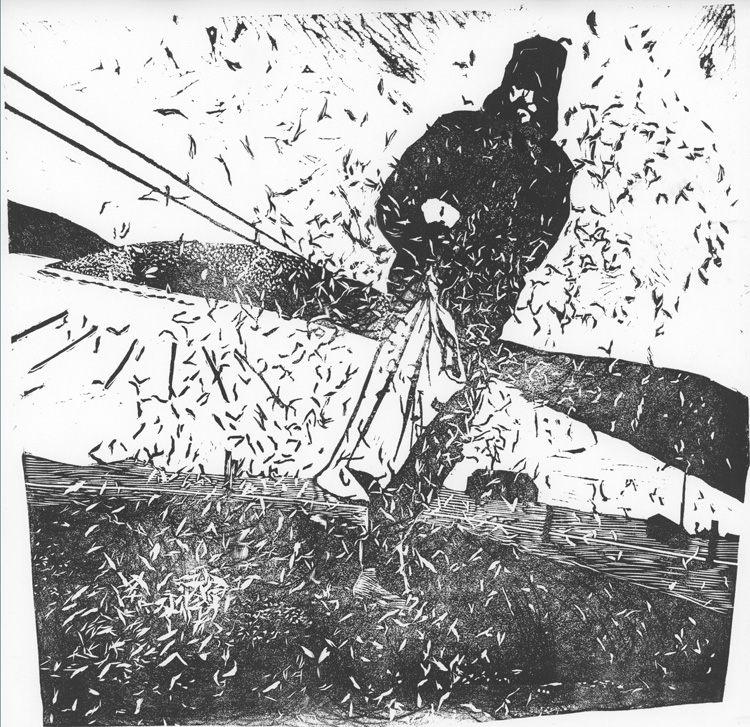

It was this tension between opposing cultural understandings of land use that underpinned the suite of drawings and prints that I exhibited in 2018 entitled: A Social Life of Peat. I wanted to demonstrate the immense scale of human involvement in the life of these blanket bogs, and to articulate its cultural value.

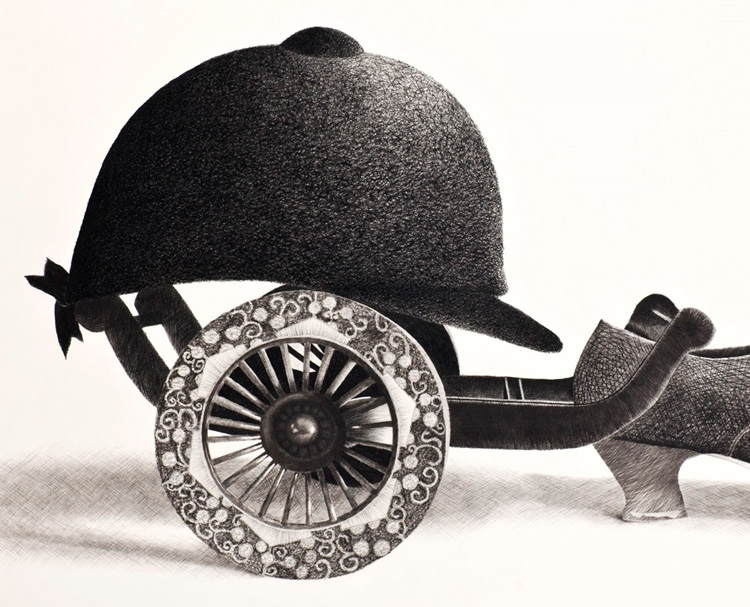

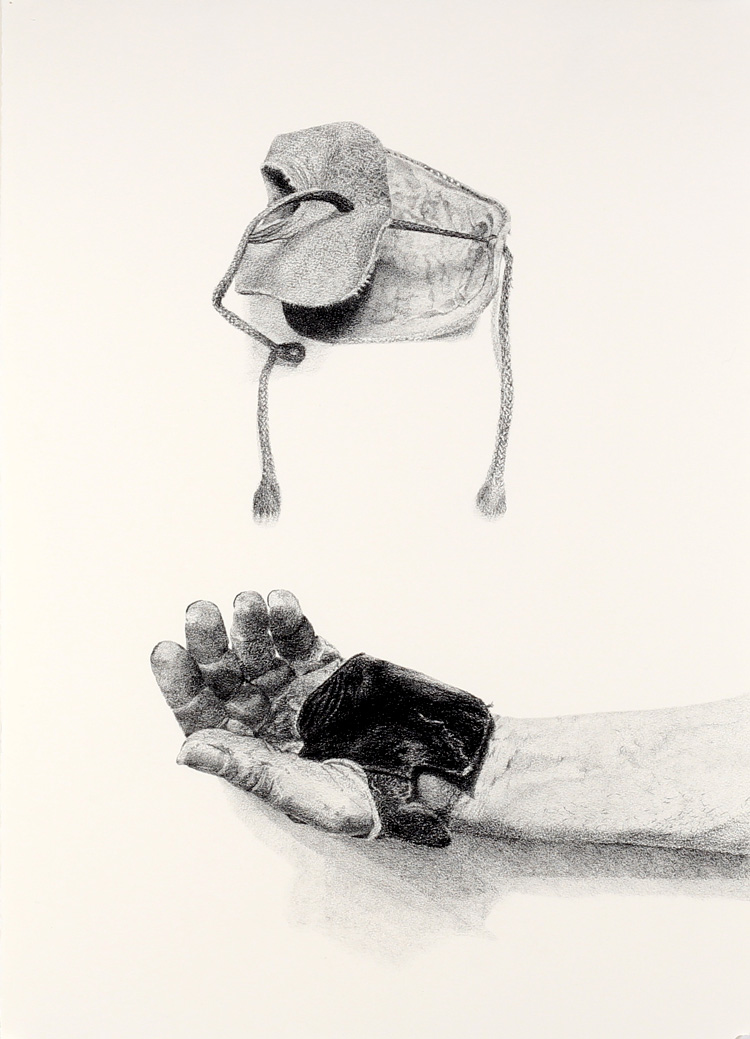

JMcK: Can you explain the impetus for your project on Shetland of Unearthed: Art and Skran, Ethnography from Shetland’s oil era?

BC: Things accumulate on these islands, borne in on the tide, or built to serve the national interest, like the oil and gas terminals and the cold-war defence systems. Unearthed explored an ancient cultural habit of Shetland islanders to salvage everything possible. Skran is a word used there that describes the act of gathering up the bits and pieces of rubbish, the flotsam and jetsam. I think of it as a term that was once associated with an indigent way of life and is now a form of cultural expression.

[image5]

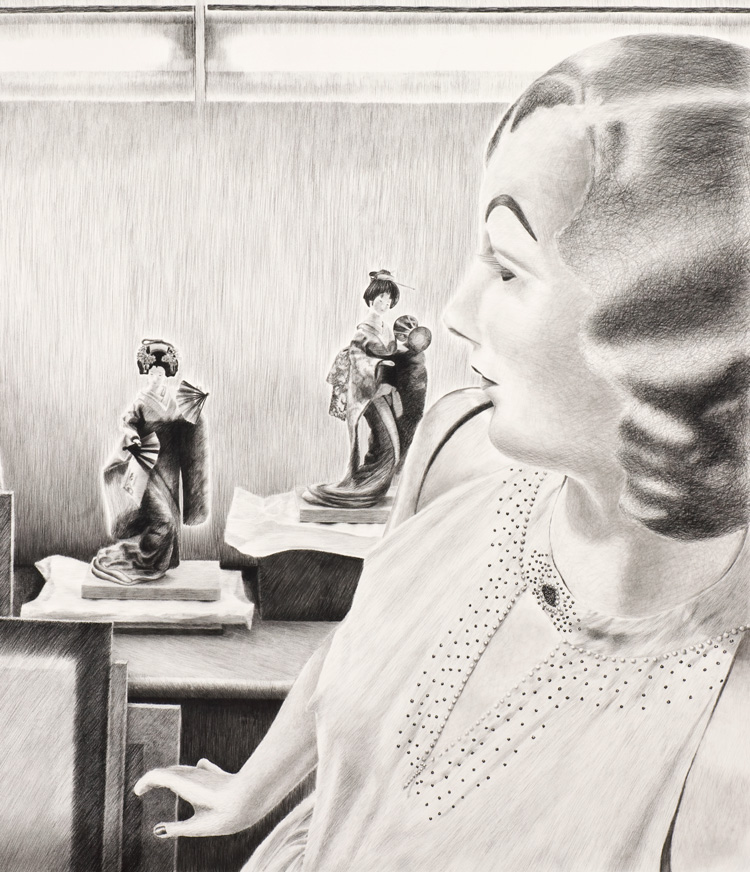

JMcK: One of my favourite drawings of yours is Sayonara Sisters (2012). Can you explain the story that prompted the work?

BC: It records an embarrassment (some time before 2011) in an Australian museum’s collection. The district had elected to terminate its twin sisterhood with a Japanese city. The dolls and other ceremonial gifts were “buried” in the store. The drawing depicts the awkward ownership of artefacts; the corollary of an unwanted relationship.

JMcK: What are you working on at the moment as we go into the very short days of winter?

BC: When cereals such as oats are grown, straw is produced. There is a type of oat that is specific to Shetland and also to a few other northerly countries. It has fallen out of production and become a rare cereal. Traditionally, its straw was used for thatching, basket-making and costumes. A handful of people still grow these oats in Shetland. I’m focusing on the indigenous knowledge that is bound up with growing, harvesting and using these oats, working towards an exhibition in 2020.