Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, Germany

30 March – 8 September 2019

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Over the past few years, the Vitra Design Museum has pioneered a particularly engaging approach to architecture in its exhibitions, examining the discipline through the prism of historic and cultural moments and trends, from the evolution of design and disco (Night Fever, 2018) to co-operative living (Together! The New Architecture of the Collective, 2017). Even though this latest exhibition focuses on the work of one architect, Balkrishna Doshi (b1927, Pune, India), it is no less inclusive and wide ranging in its themes: the title rather gives it away – Architecture for the People. Throughout the eccentric spaces of the Frank Gehry-designed gallery on the Vitra campus – itself an extraordinary collection of individual architects’ endeavours - the curators have communicated the life and the work of this nonagenarian practitioner in a way that shows how well his humane sensibility connects with the communities for whom he designs, whatever the challenges.

His 60-plus years in practice, research and teaching began with four formative years as an intern and then as a senior designer with Le Corbusier in Paris, helping him to realise his schemes in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad. He returned to India to help build new townships, homes and institutions in the post-Independence boom, completed more than 100 projects while also collaborating on Le Corbusier’s and Louis Kahn’s flagship Indian projects. Despite this, his name was not well known in Europe until he was catapulted into the spotlight in 2018, with the award of architecture’s highest honour: the Pritzker Prize. He was its 45th recipient, and the first Indian architect to receive it.

[image15]

But as Mateo Kries, the director of the Vitra Design Museum, said at the exhibition’s opening, it wasn’t the Pritzker that alerted the museum to Doshi’s talents. “You can’t do an exhibition of this scale … in less than one year,” said Kries. Rather, inspiration came from two smaller exhibitions about Doshi’s work that Kries had seen earlier: one in New Delhi in 2014 and another in Shanghai in 2016. This one introduces his unique brand of culturally and environmentally adapted modernism to his first major audience outside Asia.

[image5]

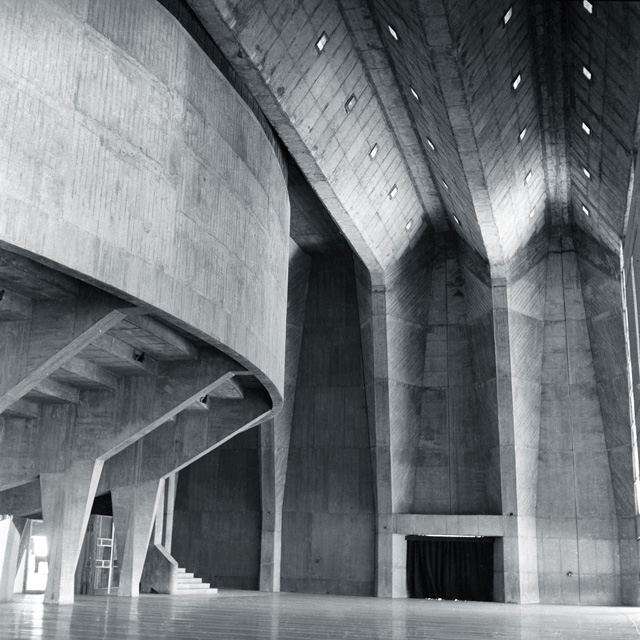

We are introduced to Doshi’s creative world with a somewhat science-fiction installation: a series of steel-mesh domes that glow from within a darkened room, representing the cave-like Amdavad ni Gufa Gallery he designed in 1994 for the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT) in Ahmedabad, the campus on which he founded the city’s first school of architecture, in 1968.

[image6]

Over five decades, he has added further institutions, as needs and funding emerged, models and photographs of which are displayed on the surrounding walls, including the Kanoria Centre for Arts (1984) and a 2012 exhibition space, which Doshi felt should include artist studios that could be leased to students after they graduated, helping to support their first steps into the world. The evolution of this campus demonstrates beautifully Doshi’s relentless curiosity and inventive spirit. The aforementioned Gufa gallery was a form so experimental that it defeated the city’s more orthodox cement construction workers, and local artisan builders - used to creating dome-like dwellings with mud - had to be brought on site to plaster the curving structure with ferrous cement, using hand tools.

In these and all other projects assembled here, we see the intelligence with which Doshi intuits how people should move through a space. The foundations for this understanding were laid in his early years with Le Corbusier, according to co-curator Khushnu Panthaki Hoof, his granddaughter and one of five practice partners in his Ahmedabad studio Vashtu Shilpa Consultants. She says: “During this time of working with him, Corbusier didn’t know English and he didn’t know French so they worked in a very cryptic language, which was really based on drawing and how people move and how people feel in space and how the light changes … In this way, he learned the essence of architecture.”

[image11]

In the following room, we are taken into Doshi’s concept of the home, with a simulation of his own home, Kamala House (1963), named after his wife, which deploys a signature setting: four pillars and a staircase lit from above. Apparently, Doshi once saw this combination on a construction site and has subsequently used these elements time and again to represent and reinvent the home, whether in designing his own or a block for thousands. The projects here include masterplans and models for several of the new townships that Doshi designed and built, for employers and Indian regional governments as the country’s post-independence population became increasingly urbanised. They are innovative, but not in ways you would expect.

[image12]

There is the residential scheme for The Life Insurance Corporation of India, in Ahmedabad (1973), where Doshi wanted to combine three different economic and social strata – a radical idea, in this caste-constrained country. Panthaki Hoof says: “The idea was the person who works under you lives above you. And each one has a place to grow and adapt, either a terrace where they could expand or they could get a garden in front of them. In order to expand, they have to communicate with the person living above or below them. For two years, nobody accepted the scheme, then people moved here. Since then, only 8% have left. Most of them have bought the house next door and expanded. All the homes have grown organically, and you can paint your houses the colour you like.” Sadly, she says, this experiment has never been replicated.

Another radical proposal was Aranya low-cost housing (1989), a huge development for the Indore Development Authority. Doshi’s masterplan involved six self-contained neighbourhoods, linked by a central spine of shops and facilities, and each with its own schools and medical centres.

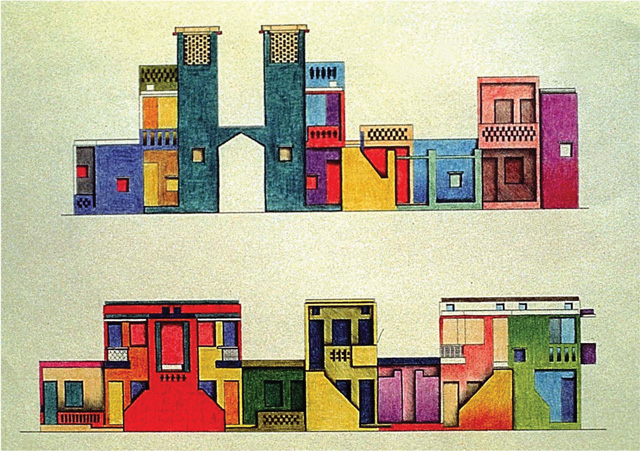

[image7]

It houses a population of 80,000 and Doshi’s revolutionary suggestion was that people should be given 30sq metres, plus water and electricity, and provided with a modular system of housing components, which allowed them to build, adapt and improve their homes according to their means and requirements. That community has thrived, says Panthaki Hoof: “These people are no longer from lower-income sections; they have all become middle income. Their children all go to school.” The Co-operative middle-income housing project for Ahmedabad (1982) is also featured here, a scheme so impressive that the Pritzker Prize jury citation said: “The entire planning of the community, the scale, the creation of public, semi-public and private spaces are a testament to his understanding of how cities work and the importance of urban design.”

[image2]

The most impactful display, however, is in the gallery that follows, focusing on work and study spaces. Here, we are invited into a foreshortened, 1:1 model of a room from Doshi’s own remarkable, barrel-vaulted office in Ahmedabad, which shrinks down to 1:2 scale. This unique office was built in 1980 and named Sangath after the Sanskrit word meaning “to accompany or move together”. Structures are semi-underground, embedded in the site’s topography, linked by a sequence of terraces, ponds, mounds and the aforementioned vaulted ceiling. The exterior walls are double layered to contain storage, their voids helping to cool the building naturally. These and other measures, we are told, reduce energy requirements by 40%. Indian classical music is piped gently along the walls to help offset the noise of traffic from the increasingly busy surrounding streets. That same soundtrack also plays gently throughout the exhibition.

[image19]

As a child, Doshi suffered burns on his leg so severe that he was bedridden for months. That experience – and most specifically, the importance of the movement of the sun in communicating the rhythm of the day – has informed one of his key school projects, also displayed here: Shreyas Foundation Comprehensive School (1963). It was one of his first commissions in Ahmedabad and he used the large scale of the site and its undulating topography to split the classrooms up and make a journey through the exterior courtyards an integral part of the day. The present-day school has been photographed for this exhibition (and the fine accompanying publication) by Iwan Baan.

The Indian Institute of Management (1977, 1992), a scheme designed by Kahn, but for which Doshi acted as collaborator and executive architect, also reveals this rich interplay between nature and structure. It is inspired by the maze-like arrangements of ancient Indian cities and temples; as one moves through a series of interlocking buildings, courtyards, gardens and galleries, tall ceilings and canopies offer shade along semi-open corridors infused with greenery.

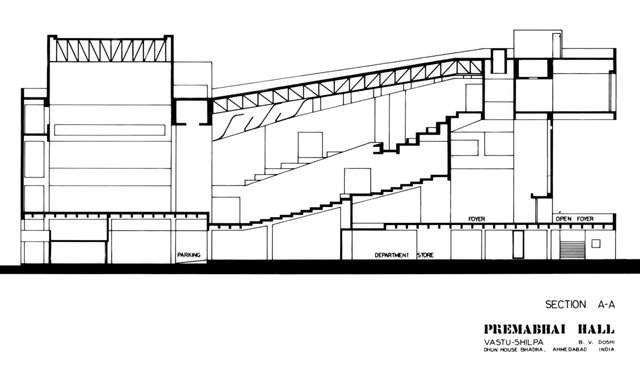

[image9]

The exhibition – generously – takes us through his failures as well as his successes. There is the monumental, concrete concert hall he designed and built for Ahmedabad, Premabhai Hall (1976), which sadly failed to achieve the funding it required to maintain a concert programme and so stands empty, in the centre of the town. But we also see that a scheme he proposed for the same site – a civic town square, at the edge of an adjacent ancient fort – has come to pass. Doshi is always thinking about how his buildings can contribute to the life of a city or a community, says Panthaki Hoof, and when he goes to visit a client with a solution to one problem, he always takes other solutions with him.

Another failure is included – and, interestingly, it is the one project that looks clunky and unresolved. A market hall and offices for 7,000 diamond merchants in Bombay; one of the few fully commercial (rather than civic or institutional) projects he has been commissioned with. Panthaki Hoof says: “After the structure was finished, the management put a lot of pressure on changing a lot of things so he left the project, and, unfortunately, this was a time when (Doshi’s) office nearly shut down.” The studio – which had expanded to premises in Bombay – was reduced to a core team of only five or six people, she says. Fortunately, it is now back up to strength, with around 60 employees, all in Ahmedabad.

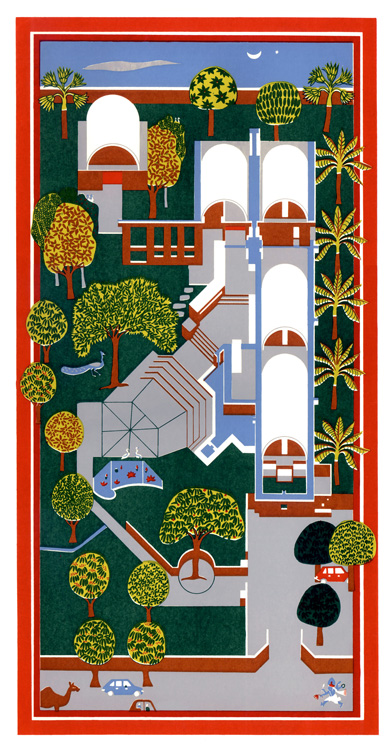

[image13]

There are several more remarkable buildings, including temples, private houses and shrines, in an exhibition that is the epitome of content rich. But one of the problems it suffers from – in common with so many architectural exhibitions – is how to convey the life of these buildings without swamping the visitor with texts, plans and diagrams. Most of the detail of what I have related above would only become apparent on a tour, which not everybody has the time for. There are a few of Doshi’s paintings – inspired by the Indian miniature style - to depict the more significant schemes which try to convey the richness of detail and the role of plans, paths, plants and people.

It is certainly worth making the effort to delve into his story and his practice, on so many levels. At the launch, Vitra Design Museum curator Jolanthe Kugler talked about the importance of showing his work in Europe. “It contains so many ideas which can help us to resolve our own problems.” Foremost among his qualities in this respect is, as she says: “His humane approach to architecture. People are always at the centre of everything he does. That is quite exceptional. Some architects build to try and make themselves immortal. Mr Doshi has never done that. He builds to empower people to build better lives.” Of this quality, we could surely do with more.