Clore Learning Centre, Royal Academy of Arts, London

22 December 2018 – 11 January 2019

by JULIET RIX

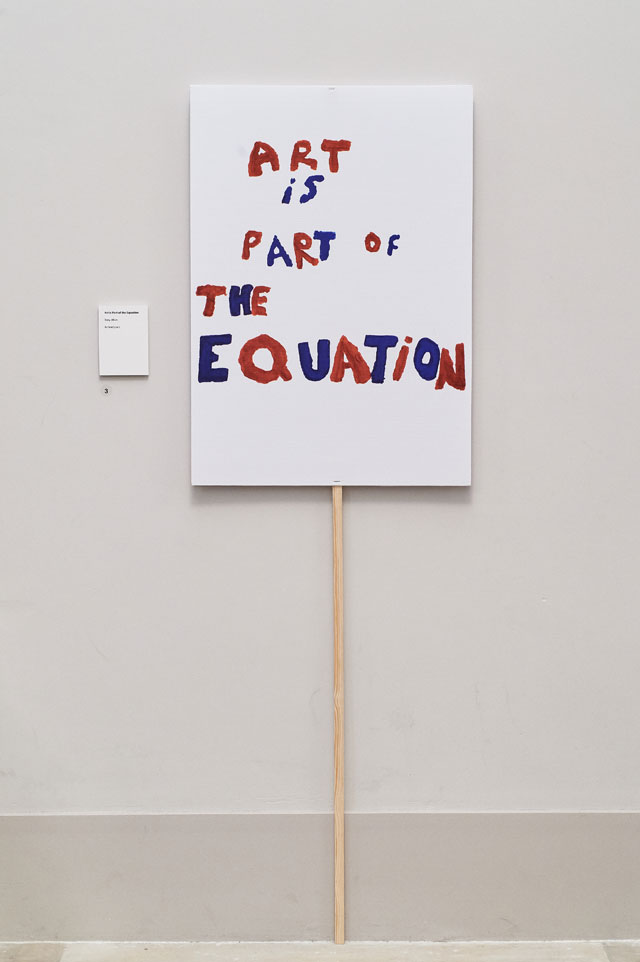

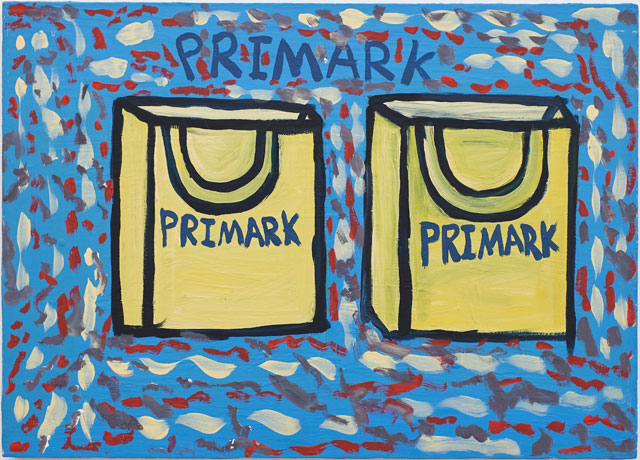

Alongside its better-known activities, the Royal Academy has been bringing art to marginalised Londoners for the past decade. Now, for the first time, it is exhibiting their work. The opening in May of the new Clore Learning Centre (where much of the academy’s outreach work now happens) has provided the necessary space. Lined with false white walls, this single large room has been hung with about 200 works by groups and individuals linked to the RA’s 14 partner organisations, which support homeless people and those with mental health problems, terminal illness and learning disabilities, among other things.

“There are so many barriers to saying you are an artist,” says Molly Bretton, the RA’s access and community manager, “but one of our Royal Academicians, Michael Craig-Martin, said: ‘You are an artist when you are making art.’ That’s how we see it. When you are making art with us, you are an artist.” It is an approach that pays dividends. Partner organisations are clear about the tremendous benefit to their clients, and some of this exhibition’s artists – artists by any definition – began to do art only as a result of referral to these organisations. It was important to the organisers to be inclusive so not all the work here would find a place in other galleries – but some of it certainly could, and the range is remarkable.

[image9]

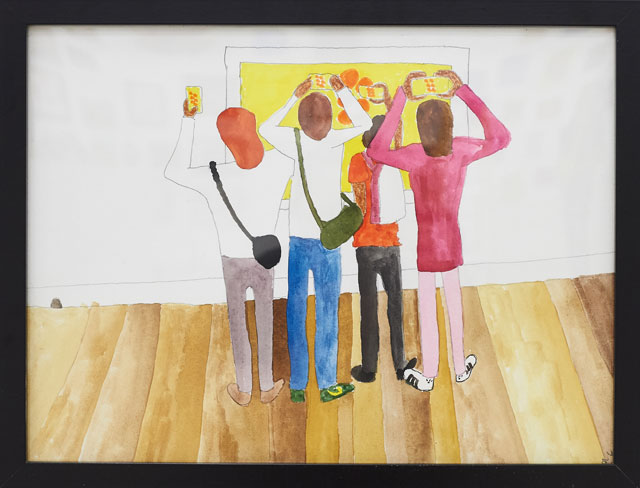

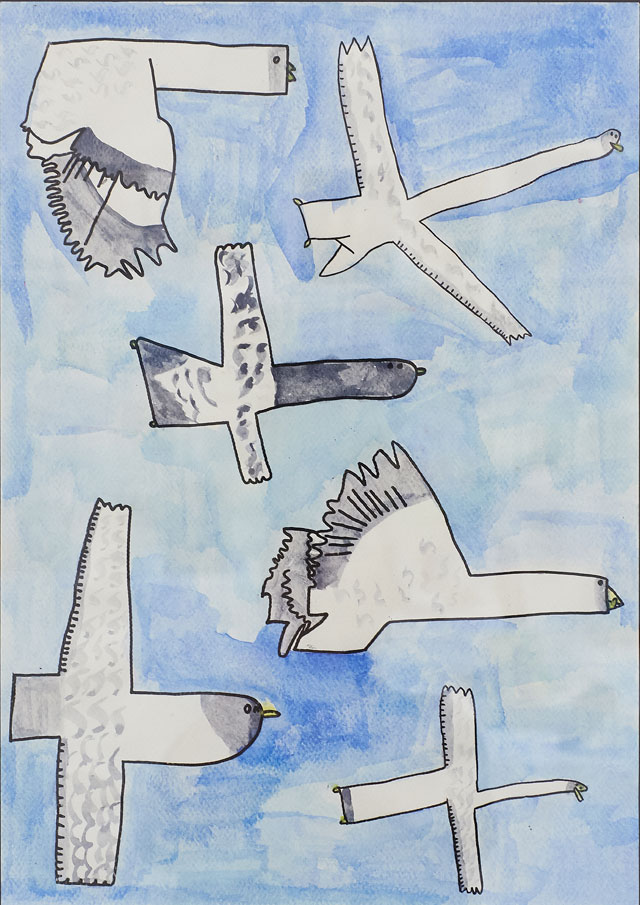

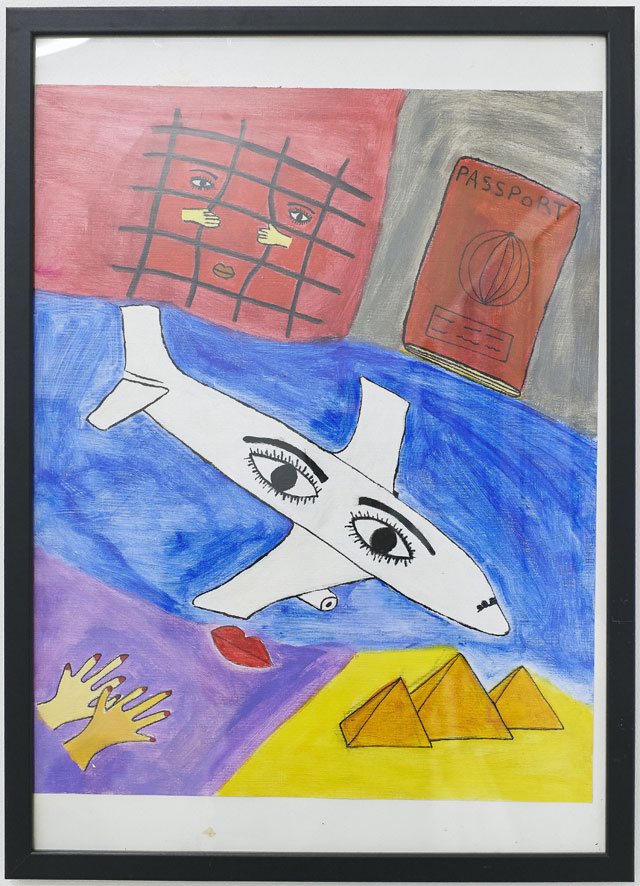

Luminous abstract landscapes hang beside personal portraits, smart urban photography neighbours gentle fabric collage, an earthy clay foot stands opposite an evocative pencil sketch like a fluid Renaissance study (entitled Man from Camden). A surreal image of a young couple (A Place Where You Cannot Return by Gusan) evokes loss of youth and country, and a graphic monochrome collage (Zenon Pardon’s Black Cats) cleverly shifts the eye diagonally back and forth across part-obscured images of everyday life.

[image2]

“The art handlers who were hanging the show were saying some of the work was better than the Summer Exhibition,” says Becky Jelly, the RA’s lead art educator, who, among other things, runs the Academy’s monthly art club for homeless people. “We’ve had a lot of members of staff wanting to buy the work.” They will have to wait. This is not a commercial exhibition, although the RA will note contact details for potential buyers and pass them on to the artists. There may be considerable competition for certain pieces.

One such is Soundwave by Chris Bird. A brightly coloured little landscape with Chagall-type hills topped with sparse schematic trees, it has a vertical sky filled with licks of colour like a felt-pen Seurat, but with a bit of white space between the marks giving them a shifting, undulating rhythm. It is both beautiful and intriguing.

Bird suffers from depression and says his art helps to keep him steady. He also makes intricate cartoony drawings in black, white and red. His Istanbul Meets London (he has lived in both cities) is ultra-urban, an organised chaos of detailed patterns, symbols and images of generic buildings and human faces merged now into a whirlwind curve, now individually, like the man in a skyscraper hat. The work is dark but not unhopeful.

[image6]

Bird was one of six artists from two of the partner organisations, Portugal Prints (which supports creative people with mental illness) and ActionSpace (run for artists with learning disabilities), who helped to curate the exhibition. Jide, from ActionSpace, whose accomplished pencil drawing of the Royal Albert Hall is in the show, explains that they laid printouts of all the works on the floor, then looked for themes and groups. Trained in advance by the RA, they worked well as a team, he says, and the hang has ended up largely as they intended.

“Putting the pictures together was like creating a painting,” adds another of the curators, Daijang Kong, a softly spoken artist from Portugal Prints whose atmospheric palette-knife oil Journey in the Ocean hangs nearby. A rolling light-blue sea of scraped-peak waves is topped by an expansive lighter-blue sky. Subtle tones and textures give it luminous depth but no definition. “It expresses my feelings,” says the artist shyly. “You can’t see your future very clearly and you don’t know what is happening next in the journey.”

How does he feel about having a painting hanging in the RA? His face, until now tentative, unchanging, breaks into a smile as luminous as his paint, but with total clarity. No need for words.

[image10]

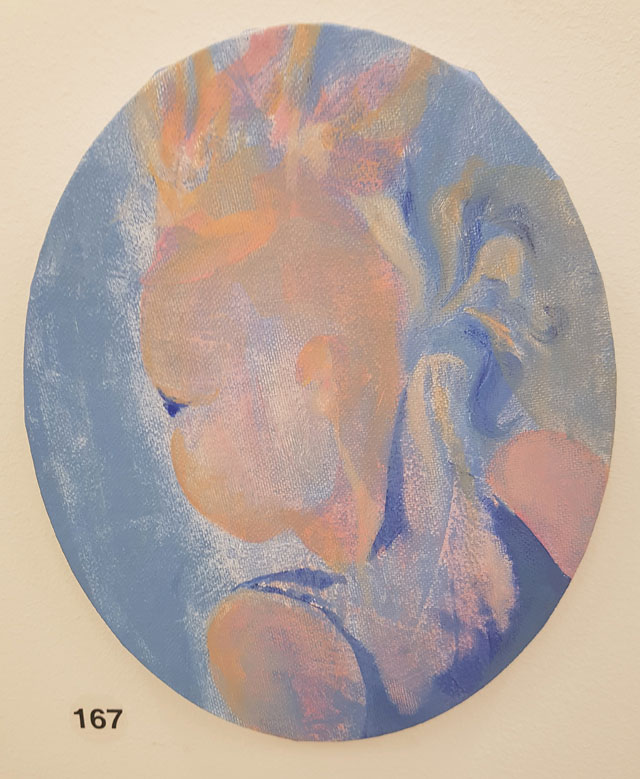

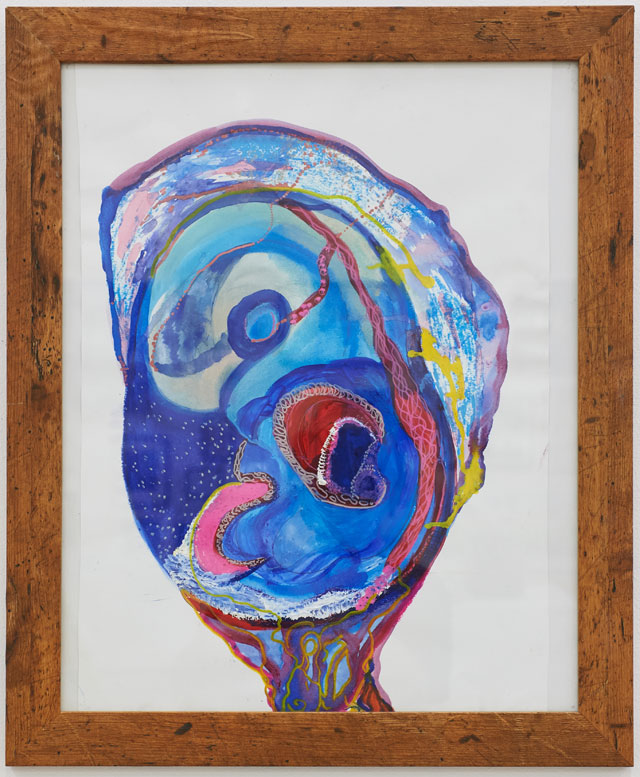

Luminosity is also a key feature of the work of Sonja Matarese, whose art has already graced the cover of the Big Issue. Her Untitled abstract painting in many shades of green, with one unsettling spot of red, owes much to her favourite artist, Claude Monet. She brings the same layered technique (scraping off as well as adding paint) and gently mysterious semi-translucence to her (also untitled) beautiful little oval, pastel-hued portrait of a girl.

[image8]

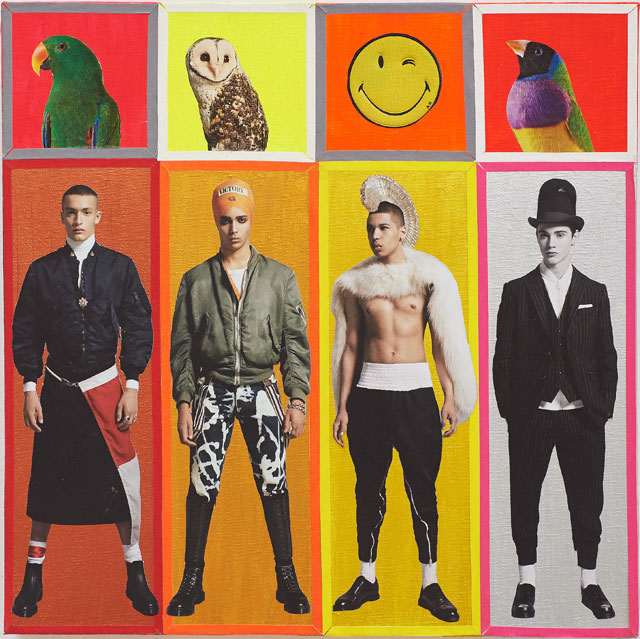

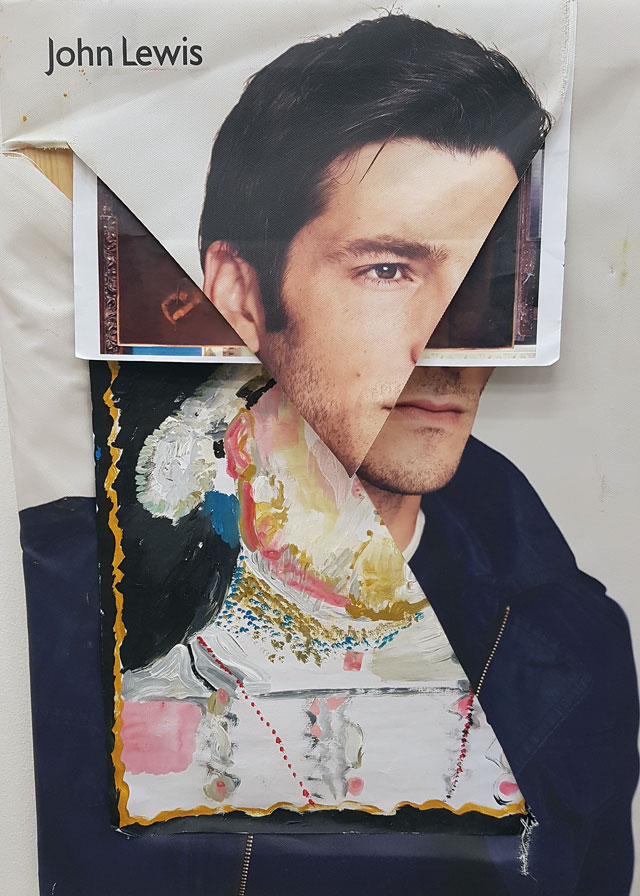

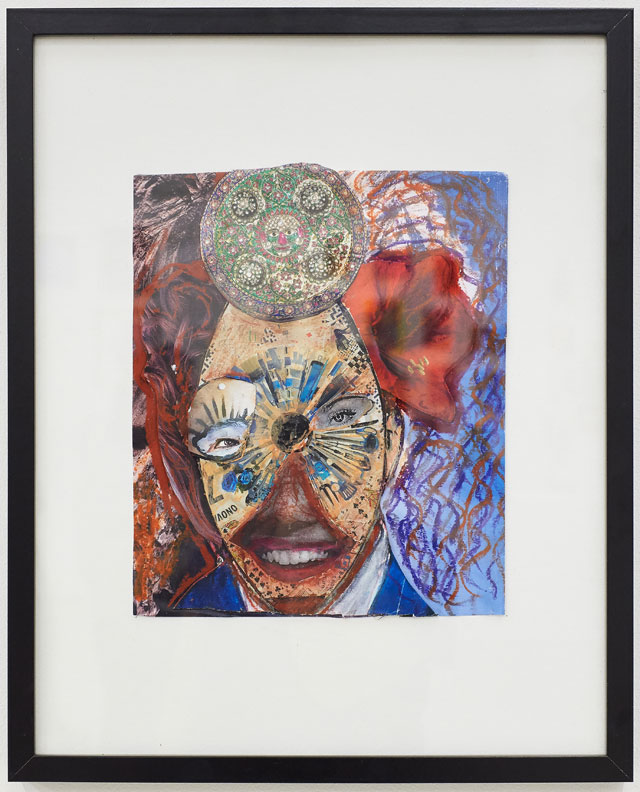

A collage by an artist who wishes to remain anonymous, but has attended the RA’s art club monthly for five years, plays with the iconography of portraiture. The work involves a cut and folded John Lewis poster of a male model that invites you to lift the flap of the model’s identity. Beneath lies Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (c1638), while the model’s torso is partly overpainted with a white, pink and golden costume that links to the title, Henry VIII History. “This work was done after we’d visited the Academy’s Charles I exhibition and talked about portraiture as propaganda,” says Jelly, “This artist is very good … very intuitive.”

[image3]

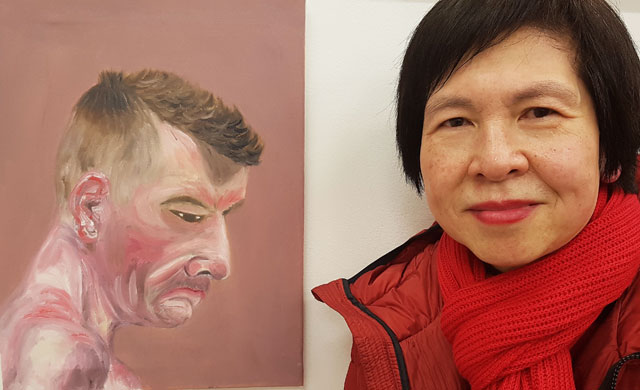

More conventional but equally thoughtful are Roseline Ma’s Lucian-Freud-like portrait of a man’s head, entitled Carer (Backbone of Society), and Aaron J Little’s touching Nana Nana Nana! showing a black grandmother lifting her grandson from a swimming pool. White highlights in her tightly curled grey hair are picked up in the drops of water falling from the baby and in the grandmother’s love-lit eyes. She looks directly at the child, while he scans the world with curiosity. But his delicate little hand on her neck gently invokes his dependence. The painting was done in part to draw attention to the loss when families fall out and grandparents do not see their grandchildren, says Little. His particular experience is of older generations “shunning” younger ones over religious differences, a practice he is passionately against.

[image4]

His link to the Royal Academy is through Capital A, an organisation that takes people who have been marginalised for many reasons to exhibitions and gallery workshops across London. The group has no base and Little often paints in London’s parks.

Many of the artists here spend more time than most outside, observing the world go by, something strikingly brought into view in one of the two video works in the exhibition. In John Watts’s powerful My England, the artist sits in a fixed frame against a wall on “the cold pavement I call home”. He turns his head from side to side following legs walking by and cars striping past between us and him. Meanwhile, in a poetic monologue he talks about his life. People give him, “sometimes change, sometimes wine … sometimes they even stop to chat about their lives … or mine”. It is understated but passionate, especially as he talks of “the stone-throwers judging my sins in the hypocrisy of their brief but vicious glances … They say life is all about choices, but there is no choice to be had on the streets of my England.”

The hope of those organising the Royal Academy’s first exhibition of its partner artists is that shows like this, and the work leading to them, might offer just a few more choices to people such as Watts – as well as pleasure and understanding to the exhibition’s visitors.

-by-Roseline-Ma.jpg)