Piers 92 & 94, New York City

3-6 March 2016

by JILL SPALDING

At long last, there is something new to say about an art fair. Bear with me, though, as I have to go through the motions first. A day after the twin VIP openings of the long-awaited Met Breuer (which is opening to the public on 18 March) and the storied Art Dealers Association of America (its usual elegant self, which held its own in quality and curatorship of the estates of deceased artists and museum-level secondary market material) a crisp wind blew the VIP crowd to Piers 92 and 94, where 205 galleries from 36 countries, showing more than 1,500 artists, spanned 28,000 square feet of thinly carpeted hallways. All the givens were present: viewer density, champagne, a broad range of dealers, and a wide selection of material involving mediums and techniques conceived to float, sprout and hang across floors, over tables and on walls. Expectations of quality, curatorship and work familiar and new were for the most part realised, and for a good part impressively. Standouts were small sculptural works, vigorous oil painting, obsessive drawing, elaborate ceramics, and a handful of the still-trending closely curated mini-shows.

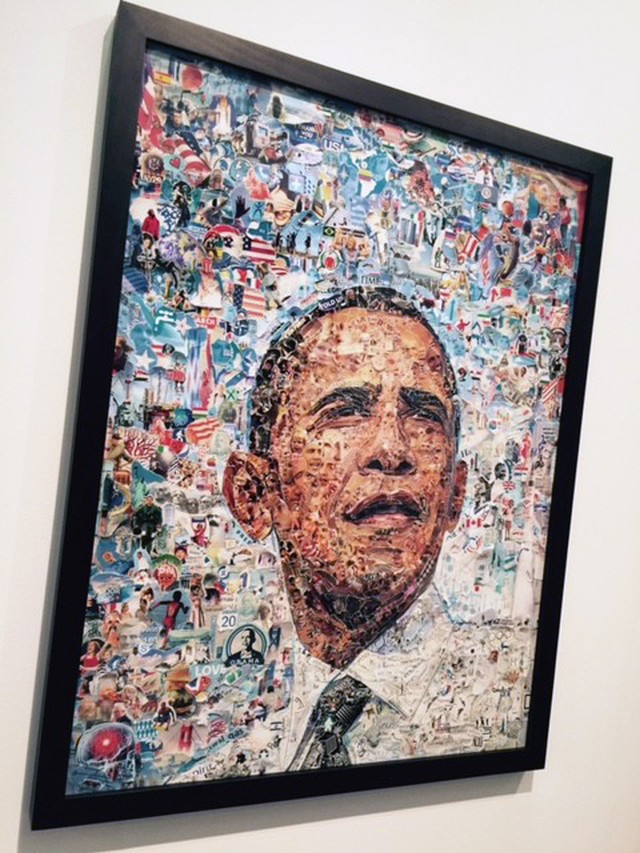

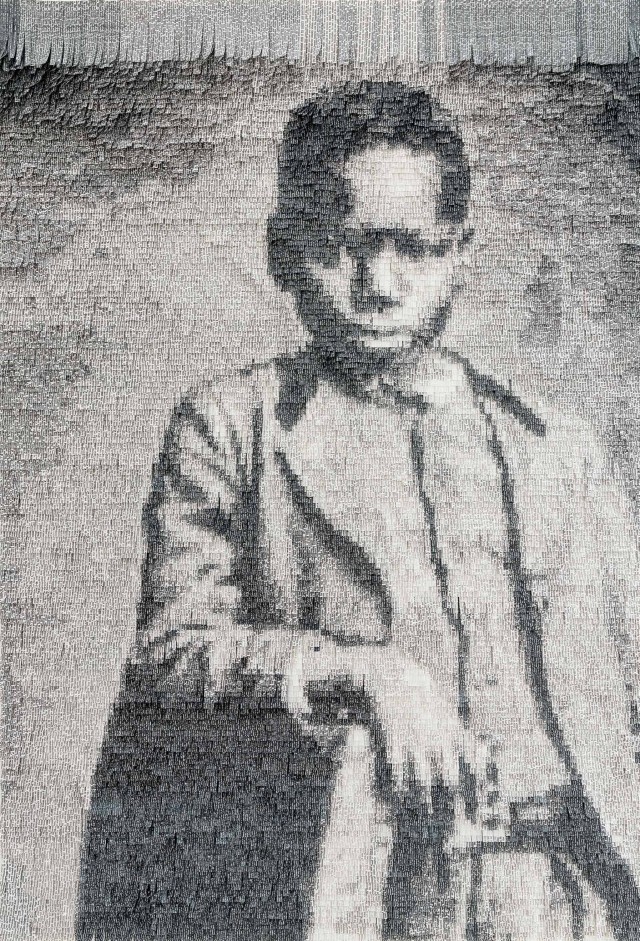

The effort of single artist presentations was left largely to Volta, the satellite fair on Pier 90 that has adopted the formula. “Too expensive now,” said Thomas Schulte, who had assembled a first-time multi-artist presentation. The exceptions were welcome – a standout, at Dittrich & Schlechtriem, was Metamorphism, Julian Charrière’s geological reset of a future consisting of melted-down tech devices embedded in post-primal magma. Photography ceded to canvas and sculpture and, speaking to fading collector interest in traditional video material by virtue of its high cost of maintenance, the moving-image works that sold here were on discs. Politically driven work was in abeyance, but where it manifested – as in #blacktivist at KOW, Mario Pfeifer’s searing double-screen video sequence of police brutality; in a Vik Muniz Obama at Ben Brown; and with Barthélémy Toguo’s painterly memorial of the victims of a terrorist attack in Burkina Faso, at Stevenson – it felt timely and strong. Refreshingly absent, work by Chuck Close, Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst; persistently present, work by Tony Cragg and Alex Katz; revived and vibrant, Larry Poons. Drawing across-the-board attention was obsessive work involving collage, weaving and drawing – Nathalie Boutté’s ink on Japanese cut-paper drawing at Yossi Milo, took the artist six months to make and sold in six minutes, earning her a solo show as soon as she can produce enough work.

The only startling factor was no startling factor. Frisson, traditionally supplied at the Armory Show by the monumental, outrageous or gross, was generally awol. Was it nerves? Dealers playing it safe in anticipation of a softening market? (If so, the strategy worked, according to reports of robust opening-day sales at the “above 50” – that’s 50,000 – level).

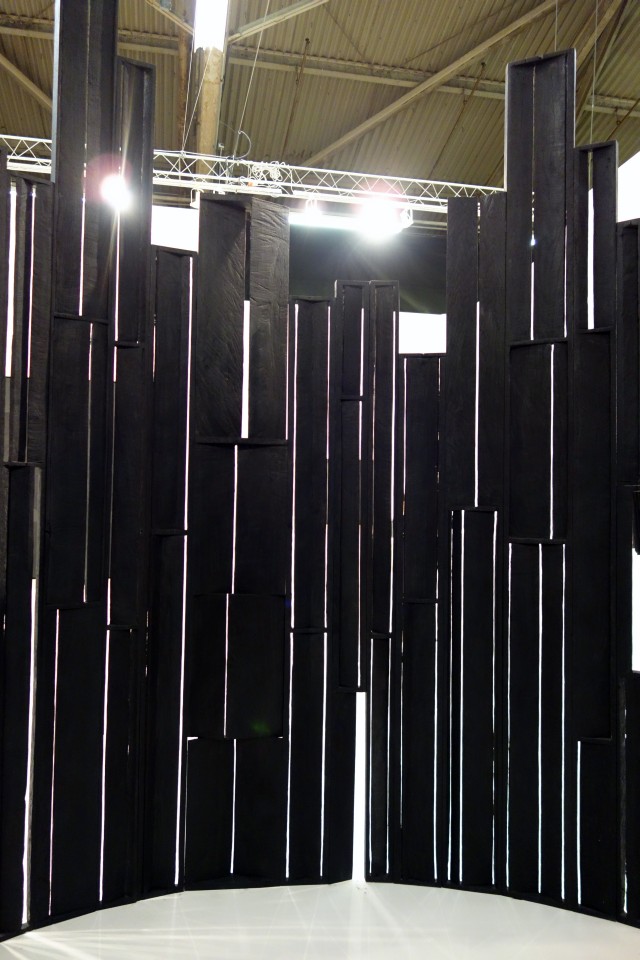

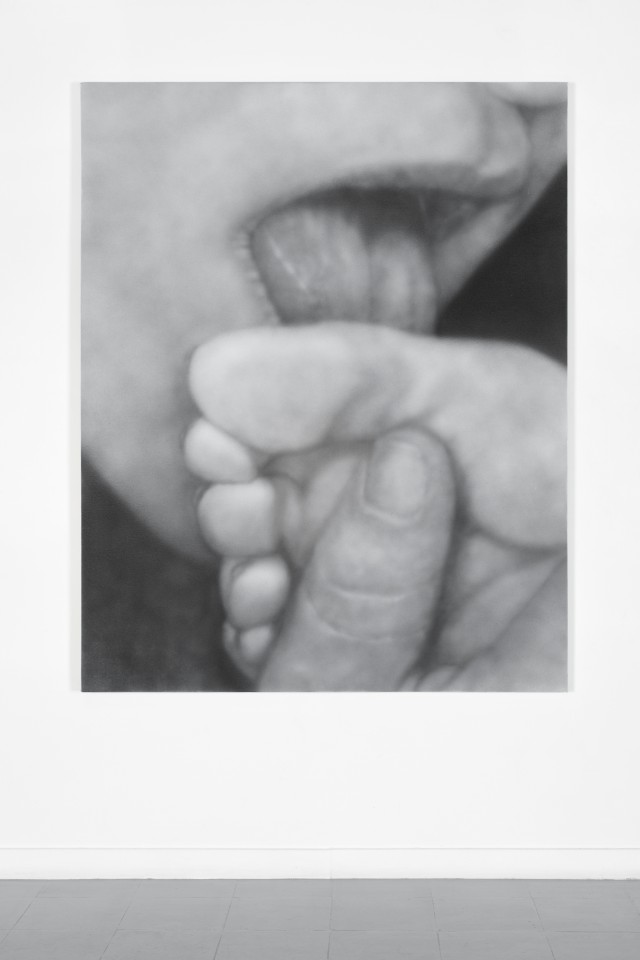

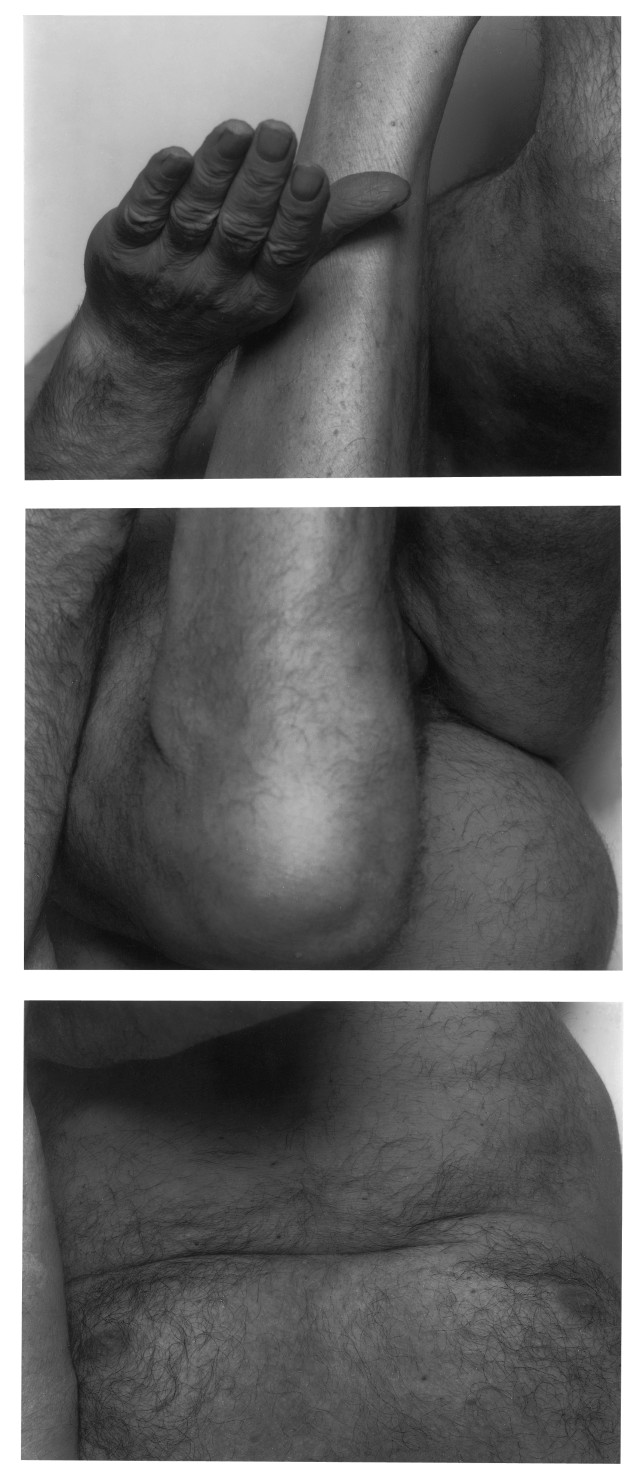

Exceptions, plus and minus, included an heroic recreation of Joan Miró’s Mallorcan studio; a looming, circular, burnt-wood installation by Nunzio at Mazzoleni, which folded you into the metaphor of a black city on a hill; and, at Donald Ellis, a wall-width diorama of small Plains Indians Ledger drawings that read both as nostalgia and guilt. In contrast, at the Breeder Gallery, Marc Bijl’s Crayola-coloured trash bag installation (priced at $20,000/£14,000!) drew groans; at Guido W Baudach, Yves Scherer’s overthought ensemble enfolding a gold nude of Emma Watson and a transgender exercise titledMerman earned the generally admired Swiss artist more press coverage than praise; at Rodolphe Janssen, Betty Tompkins’ Sex Painting #4, of a woman licking her foot, served only to elevate to masters-status Galerie Nordenhake’s superb installation of John Coplans’ auto-body close-ups; and the contortions of artist Romina de Novellis, confined nude in a cage that she was all-too-slowly obscuring with white roses, intrigued only the prurient and – perhaps with an eye on performance art for their next Art Basel Miami show – the envelope-pushing collectors Don and Mera Rubell.

The true surprise was an across-the-board feeling of tectonic shift. The change that was promised by our black philosopher-king President has finally arrived, and not only to the art world. Only those buried in selfies can have remained unengaged in our Black Matters moment. Many generations in the coming, but sparked by the election of Barack Obama, all things African American are now as much a part of the fabric of the American Experience as the cowboy and the burger. Be it Vogue cover girls (Joan Smalls, Aya Jones), male models (Armando Cabral), hit singles (Kanye West), boxers (Ngoli Okafor), TV sitcoms (Empire), news anchors (Lester Holt), movie stars (Lupita Nyong’o), or Chris Rock’s 2016 pounding theme for the Academy Awards, black is the current chic, the absolute cool and the urgent must.

Not surprising, then, that the Armory Show’s Focus section, ever a measure of where attention must be paid, is on Africa. The surprise is the level aspired to, the level attained, and the reach. Leaving the media to bring “the west and the rest” up to speed with how much black lives matter, curators Julia Grosse and Yvette Mutumba aimed to move western culture beyond a disingenuous take on the African-American Experience to a more sophisticated understanding of the pan-African Perspective. In a multicultural world, they wanted us to see that “art from Africa and the diaspora can look, sound and feel many different ways”, and how artists who are identified as African, but who identify as transglobal, challenge the assumed African aesthetic and see their country of origin only as a point of departure. Focus: Africa was curated to show that the new African presence may have filtered through the diaspora as a metaphorical collective, but that its variant practice is nuanced and complex: that the work of artists known in their own right, such as South Africa’s Jane Alexander, Angola’s Francisco Vidal, Nairobi’s Cyrus Kabiru, Egypt’s Ghada Amer and Senegal’s Mame-Diarra Niang, is both singular and connected by community and their part in the rebirth of an ancient continent.

Africa is not a logo: an artist with a connection to Africa need no longer portray its visual taglines. Work by a Ghanian artist based in London resonates with work by an artist based in Yogyakarta. The artist Ato Malinda was born in Kenya, studies in the US and works now in Rotterdam. Kapwani Kiwanga, Armory 2016’s commissioned artist, was born in Ontario, studied anthropology and comparative religion at McGill University in Montreal, was artist-in-residence at top institutions in Dakar, Le Fresnoy, Tourcoing and Eindhoven, now lives in Paris, and addresses historical interpretation through visual investigations ranging from the manufacture of sisal to diplomatic gifting to a UN secretary general.

Revealing, too, the wide range of methodologies; reshaped by a stunning variety of tools, mediums and voices, the distinction between them is not subtle. There was equally powerful work in weaving, photography, painting, sculpture and installation. Dan Halter’s Patterns of Migration at What If the World wrested a headless, walking man from woven plastic bags; Blank Projects featured Turiya Magadlela’s wallhangings stitched out of pantyhose sourced from African prisons; Cyrus Kabiru’s photo-portraits at SMAC translated the ceremonial mask into sculptural eyewear. Brightly coloured perspectives drew viewers to Eddy Kamuanga Ilunga’s poignant canvases at October Gallery, Emanuel Tegene’s newly minimalist Hypocrite l at Addis Fine Art, Francisco Vidal’s graffiti-inflected Portrait Series at Tiwani Contemporary, and Kudzanai Chiurai’s ambitious storefront, Emporium, at Goodman, complete with mannequin, trolley, prints and wallpaper. Along with new talent, Focus: Africa showed work of the artists who inspired it; at Vigo, Sudan’s legendary Ibrahim el-Salahi, the first African-born artist given a retrospective at the Tate, was lyrically represented by his signature black-and-white calligraphic drawings; El Anatsui, miraculously, was represented by himself – no one believed that the shy, elderly artist would make it over for the scheduled symposium, but he did.

What was truly new about Armory 2016 was less the Focus section itself – a yearly feature – (those on China and the Middle East remain memorable), than that this year’s lens on Africa widened out to the fair’s storied galleries – Sean Kelly, Paul Kasmin, Yancey Richardson, Howard Greenberg, Jack Shainman, Victoria Miro and Alison Jacques among them – introducing the notion of dealer as curator, teacher and, by association, tastemaker; the pundit with a finger on the zeitgeist who now openly drives the direction taken by both collectors and artists. Cases in point: by aligning Barkley L Hendricks’s pop-pink Photo Bloke painting with Nick Cave’s Soundsuit sculpture, a Toyin Ojih Odutola ballpoint pen drawing and Kay Hassan’s photographic composition, Shainman gave substance to the trending term “Afrofuturism”; by pairing of a portrait by Alice Neel with a diptych by the two-generations-down Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Victoria Miro turned a mental stretch into cultural fusion; by placing Kehinde Wiley’s powerful new bronze sculpture Bound, a deeply moving meditation on African identity, alongside the majesty of Robert Mapplethorpe’s Ada, Sean Kelly raised the decorative appeal of this purveyor to white walls to an entirely new level.

It marked, too, that, excepting Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden (both bought up since their Whitney outings) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (too token?), the pioneers were paraded; Betye Saar, Horace Pippin, Gordon Parks, Kerry James Marshall, Henry Taylor. Trailing them were the next-ups, each represented by signature work – a Kara Walker silhouette, an Isaac Julien photograph, a Mickalene Thomas rhinestone celebrity, a Chris Ofili stereotype, a Wangechi Mutu collage. Pulling the urgency up to the show’s Modern section on Pier 92, Howard Greenberg showed wrenching material by Alex Majoli. Continuing on to Pier 90, Volta broke out nine notable African artists (two of them present); Cameron Platter (South Africa), Paul Onditi (Kenya), Wycliffe Mundopa (Zimbabwe), Ibrahim el Dessouki (Egypt), Dawit Abebe (Ethiopia), Gonçalo Mabunda and Mário Macilau (Mozambique), Aboudia and Armand Boua (Cote d’Ivoire).

Most heartening was the strong presence of African viewers, dealers and collectors, many in themselves works of art. Their imprimatur made for a fair that seemed to have moved beyond shopping, or at least brought commerce into a realm that felt meaningful and adult.

Shih Chieh Huang. Disphotic Zone / Twilight Zone, 2015. Installation. Sound, light, electronic machinery, plastic bottles, plastic bags. Ronald Feldman Fine Arts. Video: Miguel Benavides.

There was a lot of everything else, of course; Asia, Latin America and Europe were fully represented, and it drew attention that Habana was the Armory Show’s first dealer from Cuba. Crowd pleasers were Ivan Lam’s illusionist portraits composed of painted strips, Shih Chieh Huang’s black-box booth installation of fluorescent bioforms, Robert Rauschenberg’s rarely seen bicycle/airplane composite, Claude Lalanne’s Pomme d’Hiver, barely known table-top sculptures by Lucio Fontana, Nick Brandt’s outsize archival print superimposing the memory of an elephant on to a denuded landscape, and prime examples of Linda Lopez’s elaborate ceramics recently profiled at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Selling fast; Sebastiaan Bremer’s Flower Series, Spencer Finch’s lightbox abstractions and Matthew Monahan’s grim limited-edition sculptures of a man shot at close range by a Colt 45 pistol.

People-watching turned up Hollywood’s Matt Damon and Steve Martin, collectors Eli Broad, Bernard Lumpkin and Hubert Neumann; museum directors Glenn Lowry and Anne Pasternak, and art shakers Jeffrey Deitch and living legend Irving Blum. Free stuff topped out with artist Ed Young’s bobbing black balloon lettered “Your Mom” that I attached to a button, and candy-coloured bags by Douglas Coupland with your choice of irreverent sayings; I wanted turquoise, so headed out with “I Can Feel The Money Leaving My Body”.

Those with feet still attached to their body carried on to the satellite fairs, headed staunchly by Pulse and, more compellingly, by Independent (less scrappy in its new Tribeca warehouse venue, and less well attended because, no longer free, entry now costs $20) and most appealingly by the dazzling Spring/Break fair that featured thoughtful, energetic booths designed by actual curators around affordable and original, if dauntingly onsite, work by very young or lesser-known artists.