Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

10 March 2017 – 2 July 2017

by JULIE BECKERS

The spacious rooms in the elegant Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium explore Rik Wouters’ work in the well-lit lower ground area, like most of the temporary displays in this museum. The set-up of the exhibition is thematic and, sparse of much extra information. This sparseness is an intentional curatorial decision to allow the visitors to really focus on the work in front of them. The exhibition wants to draw the attention to the works themselves and motivate visitors to observe rather than read labels. This stimulus makes sense, as Wouters’ oeuvre doesn’t demand an elaborate textbook approach.

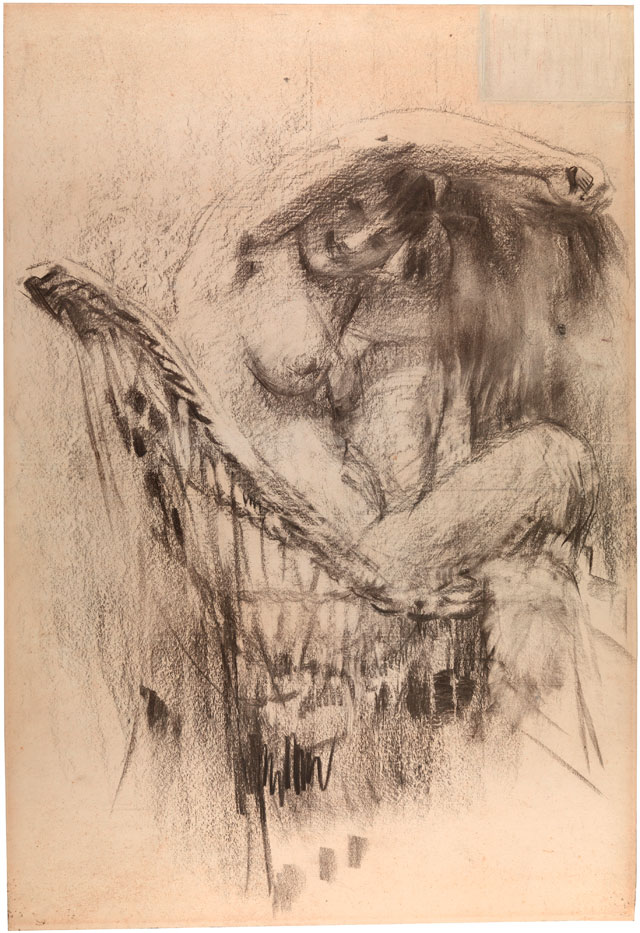

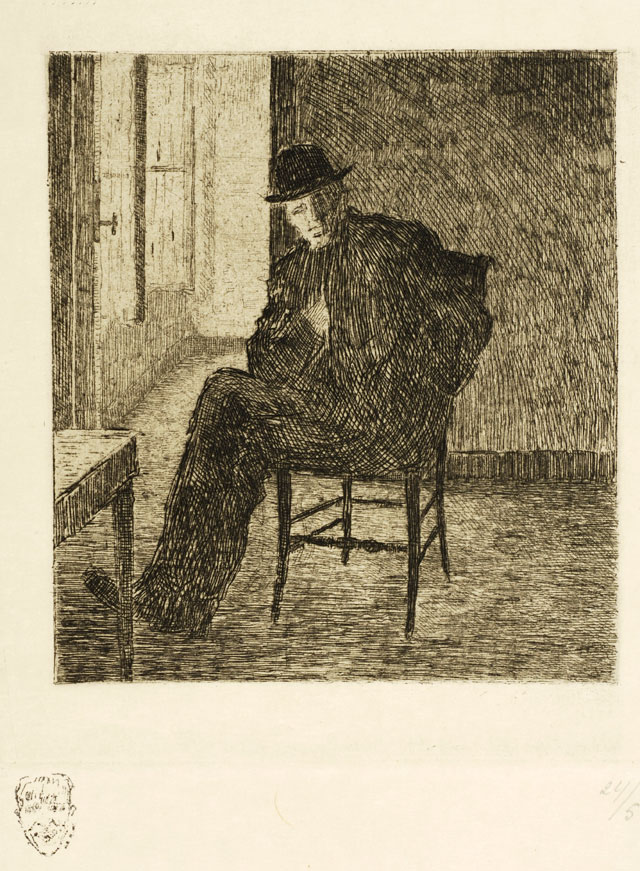

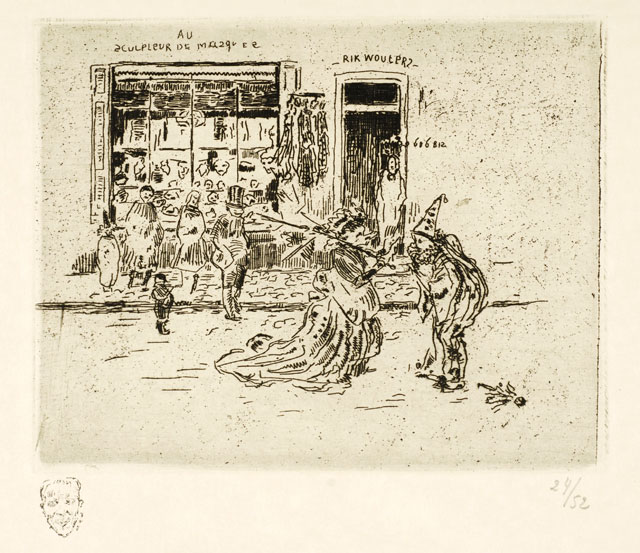

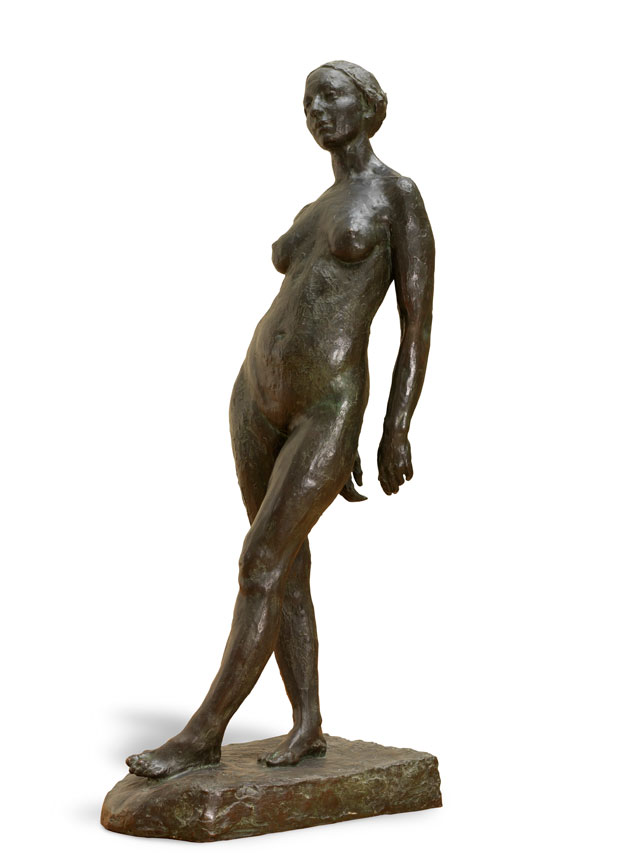

His colourful work is characterised by authentic and touchingly simple depictions without hidden iconographical messages. He paints, draws, and sculpts pieces that explore ideas of homeliness, warmth, and intimacy in which his wife, Nel (Hélène Duerinckx) features as his muse. Wouters (1882-1916) shies away from the canonical topics that explore mythology, religion, politics or social change; his work looks intimate and does not include symbols or allegories, and therefore Wouters is perhaps considered as more conservative in comparison with some of his French and Russian fin-de-siècle colleagues who provoke audiences through their membership of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter.

Many paintings by Wouters give the impression of not having been finished; Woman in Black reading a Newspaper (1912) is a good example. Large swaths of canvas are sometimes left blank and untouched.1 There is no immediate explanation for this artistic process, although it is not unreasonable to claim that a seemingly unfinished piece for the audience is a finished product for the artist, whereby he invites the observer to finish the strokes on his behalf. Wouters, according to his early critics, was a terribly active worker, often starting new projects while pigment was still drying on a recently touched canvas. Paul Cézanne, to whom Wouters has often been compared and who obviously uses the “moment” as his most prevalent motivator, committed to a similar practice. This can clearly be seen in his The Garden at Les Lauves of 1906. The seemingly fleeting artistic practice that Wouters adapted does give us the chance to admire an enormous oeuvre finished roughly between 1902 and 1916 when the artist died at the age of 33.

Wouters’ early work, produced around 1904-05 and after he had taken lessons from Jan Willem Rosier at the Mechelen academy, was characterised by classical portraits, influenced by the Belgian symbolist Fernand Khnopff to whom he looked for the depiction of the Portrait of a woman in grey (First portrait of Nel) (1904-1905) and Portrait of a young boy (Victor Dandois) (1905), here on display. Wouters’ brushstrokes are less smooth than Khnopff’s and one can, at this early stage, already note hints of his later style, which would be typified by colours applied in striking contrasts, with a frequent use of white and bright tones. This evolution seems to come to full bloom in the years 1911-12, when he paints a self-portrait, Portrait of Rik (without a hat) (1911), Woman in an interior (interior A) (1912),and the astonishing Woman ironing (1912), all on display in the exhibition. His canvases equally become more complex in terms of composition. Wouters starts to apply thin layers of paint, which he then works up with pastose brushstrokes, giving rise to complicated textures through which some details in his paintings look like solid volumes creating vital contrasts.

Wouters’ strive to develop a strong interest for light in his depictions succeeds in bringing his figurative work to life simply by indicating line and colour. This is most obvious in his Woman reading and Autumn ( both 1913) and the portraits he painted of his friend Simon Lévy after the two had met in Paris in 1909 when Wouters had competed for the Prix de Rome.

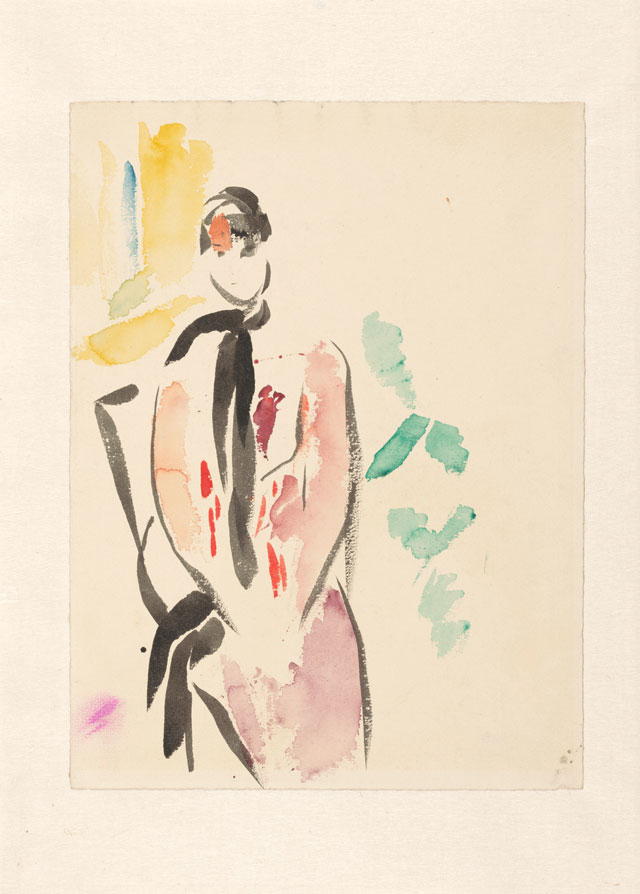

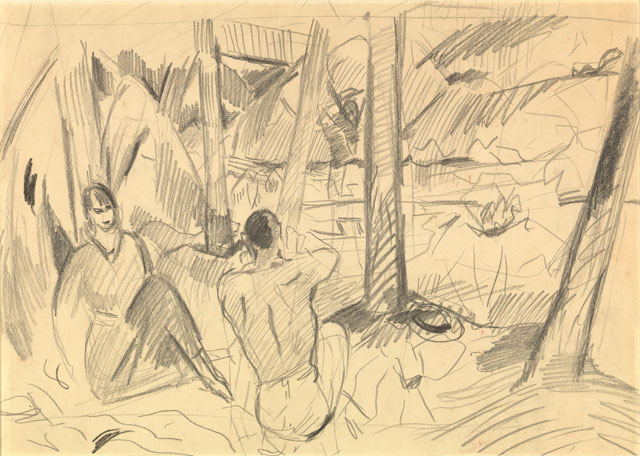

During the first world war, Wouters was mobilised to the front in July 1914 and spent several months in a prisoner of war camp in the Netherlands, where he had been captured in November 1914. From the camp, Wouters managed to produce drawings and aquarelles, on display in this exhibition, exploring life and death at the camp. These images, such as Belgian soldier selling trinkets, barrack 18, camp Zeist (1914), capture the artist’s despair: Wouters was appalled by the ugliness of war and missed his wife terribly. He started suffering from terrible headaches and, possibly as a consequence of both his declining health and his wartime experience, Wouters’ palette turns sombre, using browns, greys and dark blues. Testimony to this change in mood are the poignant paintings Self-portrait in green hat (1915)and Woman seated near window (portrait of Nel Duerinckx, wife of the artist) (1915), which are found in the final room of the Brussels show. In particular, the dramatic Self-portrait with Black eye patch (1915-16) paints the personal struggle Wouters, who had lost an eye to cancer during the last months of his life, went through. Wouters, with eye patch, died on 11 July 1916, leaving behind Nel and an enormous oeuvre.

The retrospective exhibition in Brussels succeeds in its aims; it allows visitors to fully engage with an artist who might not yet be known across international borders and continues to build its impressive national programme showing off Belgian masters. Through about 72 paintings, 33 sculptures and 95 drawings, Wouters emerges as a conqueror of colour and composition, and through the interlinking of swift and broad brushstrokes his wife Nel emerges, while his landscapes and drawings explore personal struggle and strife. Observing is, indeed, at the forefront of this exhibition with, and perhaps this is a shame, little extra reading beyond the biographical section at the start of the exhibition. The catalogue, as always, does provide an informative and chunky cure.

Reference

1. Rik Wouters, A Retrospective, 2017, published by the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, page 20.