The Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion

Metropolitan Museum of Art

6 May–9 August 2009.

by CINDI Di MARZO

Since the advent of the supermodel during the 1980s, such stars of the industry as Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, Kate Moss, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington and Gisele Bündchen have commanded the attention of an international audience crossing genders and age groups, while securing impressive fortunes in the process and expanding their careers as actresses, brand spokeswomen, philanthropists and designers of clothing, home fashions, shoes, handbags and jewelry. Modelling's rags-to-riches rise has a fairy tale quality about it; early models were called mannequins, their names and identities held to be inconsequential by Parisian couture luminary Paul Poiret, among others. The sea change can, perhaps, best be gauged by top-earning model Gisele Bündchen's personal story: Discovered at age 13 while eating at a McDonald's in São Paulo, Brazil, Bündchen, a Brazilian of German descent, has appeared on Forbes magazine's list of most powerful celebrities and, reportedly, has a near 35 million-dollar annual income.

The Costume Institute's annual gala benefit took place this year on 4 May and kicked off the exhibition. Followed by a deluge of media coverage and photos, the gala was as press-worthy as the supermodels, actors, musicians, fashion designers and socialites (totalling approximately 650 guests) who attended. These included Madonna, Donald Trump (who owns a modeling agency) and his model/wife Melania, Kate Hudson, Victoria Beckham and Renée Zellweger; designers Carolina Herrera, John Galliano and Donatella Versace; as well as models well represented in the show (Twiggy, Beverly Johnson, Brooke Shields, Lauren Hutton, Carmen Dell’Orefice, Crawford, Iman, Moss and Bündchen). Designer Marc Jacobs, who funded the exhibit with additional support from Condé Nast, served as honorary chair of the gala; Moss, singer Justin Timberlake and American Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour served as co-chairs. John Myhre with Raul Avila designed the event based on the decor of the now-closed Manhattan nightclub El Morocco. A Zebra-print theme took shape as a runway that led past a six-foot mannequin in the museum’s Great Hall, representing the Muse in all her glory.

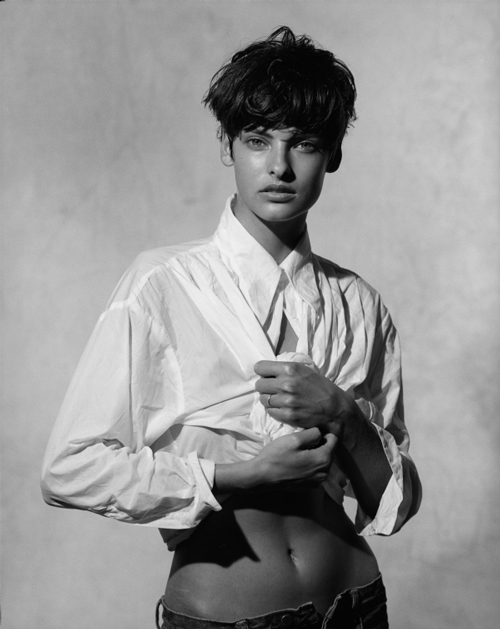

For those of us not on the guest list (and who did not try to crash the event as did hip-hop record-label pioneer Russell Simmons), the exhibition provides entry into the high-stakes realm of fashion modelling. Moving through the rooms, organised by decade, is like being submerged in images from the past, whether our own or that of our mother or grandmother. Although there are nearly 80 examples of haute couture and ready-to-wear garments, the focus of The Model as Muse is on the fashion muses who have had nearly earthquake-like effects on conceptions of female beauty. As they have done in editorial layouts and print ads, on runways and as the representatives of brands ranging from clothing and perfume to watches and soft drinks, these faces stare back from the walls and pages of magazines propped in display cases, begging for identification. 'You know me', they seem to say – and it is true; unless one has lived under a rock, each face seems somehow familiar.

Available in hardcover and paperback editions, the catalogue1 written by exhibit curators Harold Koda, Curator in Charge of the Costume Institute, and Kohle Yohannan, guest curator, is sublime, providing a deep visual and verbal exploration of modelling and fashion culture from 1947 to 1997. The author of several books on fashion design and designers, Yohannan curated the Valentina show at the Museum of the City of New York that recently closed.2 As he and Koda remark in the catalogue prologue, 'Cultural awareness of modeling as a respectable, stand-alone profession was slow in coming. And despite the fact that a socialite or showgirl may have been motivated by the prospects of the increased fame and heightened prestige that came with appearing in a fashion magazine, it was not until the mid-1920s that the fashion model began to emerge as a fully formed social and professional entity'. In the post-World War II period, modeling came into its own.

In the post-war era, the American fashion industry, advertising agencies and emerging model agencies worked in tandem, enticing women of all classes to base their dreams on what they saw within the pages of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar and in ads that these and other women's magazines featured. Christian Dior's so-called 'New Look', a term drawn from a comment made by Harper's Bazaar editor-in-chief Carmel Snow, grew out of his 1947 spring/summer collection. For it, the designer offered an appealing change from the frugal, pared-down aesthetic dictated by post-war realities. His mid-calf-length full skirts, generous bust lines and cinched-in waists were, to many women, a welcome relief. Dior’s feminine silhouette heightened the attenuated elegance of models Lisa Fonssagrives, Dorian Leigh, Dovima, Sunny Harnett and Suzy Parker, as captured by photographers Irving Penn (Fonssagrives' husband), Lillian Bassman, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Cecil Beaton, Richard Avedon and John Rawlings. The drama of many of these photographs, particularly Richard Avedon's shot of Dovima with a group of elephants (Harper's Bazaar, September 1955) at the Cirque d'Hiver in Paris, suggested to women who would never wear haute couture that fashion was, indeed, a grand show. Clothing could set the stage, but the woman who wore it held the key.3

Koda and Yohannan state in the catalogue, for example, that Sunny Harnett 'projected a highly evolved notion of sophistication', while Dovima often projected 'an otherworldly exoticism–half Japanese geisha, half Flemish Madonna'. They add that 'as with every great model, Dovima was also able to convey a range of effects without diluting her own distinctive identity'.

A distinctive identity links Dovima and her peers in the fifties with models in the succeeding decades of seemingly disparate characters and fashions: the sixties' British Youthquake rebellion; seventies' All-American pie, athletic look; eighties' personality-driven supermodel-era; and nineties' grunge-influenced street styles. Visitors to the show should keep in mind this link as they move through the galleries; one of the most delightful aspects of the show is its appeal to teenagers, college students, budding designers, mothers, career women and their grandmothers. In the huge crowds attending are women who owned copies of the large-format, fifties-era magazines displayed in the cases; women who remember Twiggy's journey in 1967 from her native England to America, sporting her androgynous, twenties-era flapper-ish body and puckish haircut; women who watched as fresh-faced Christie Brinkley and Cheryl Tiegs were joined by black models like Iman and Beverly Johnson and other representatives of more inclusive definitions of beauty; and women on the brink of womanhood who see themselves in models wearing leather, flannel and chunky shoes.

After the sixties, many designers began seeking ethnically diverse models for print ads and on runways. Koda and Yohannan do an excellent job of teasing out milestones, particularly those that are democratising benchmarks for women, for instance, Donyale Luna's status as the first notable African American model and first black cover girl (British Vogue, 1964). A major theme of the exhibit and catalogue is the ever-expanding earning potential of women who actively contributed to the design process while functioning as muses for designers (Peggy Moffitt for Rudi Gernreich); produced iconic shootings with photographers (Lisa Fonssagrives for Irving Penn; Jean Shrimpton for David Bailey; Linda Evangelista for Steven Meisel); and inspired artists and filmmakers (Luna for Andy Warhol) and musicians (Jerry Hall for Mick Jagger; Patti Hansen for Keith Richards). Fashion muses have been self-determining, negotiating high-power careers and even garnering a place on a Forbes listing. Koda and Yohannan also point out instances in which models, whose faces are ubiquitous but whose lives are often a closed book, have gone against the grain, revealing their personal struggles to the public (Luna and Gia Carangi, whose early passings affected their generation, and Moss, who continues to be a symbol of the times).

Aside from highlighting culture-altering aspects of modelling careers, the exhibit is also great fun. Each exhibition room has a soundtrack, with a song chosen as a symbol of each period. On one wall of the Youthquake space, visitors can watch New York City-born filmmaker William Klein's 1966 French film spoofing the high-fashion industry, Qui êtes vous, Polly Maggoo? (Who are You, Polly Maggoo?), starring Brooklyn, New York-native and model Dorothy McGowan. Mannequins on platforms in the center of the space display metallic dresses worn by the actors in the film, while others model fashions by some of the era’s most influential designers.

The final gallery includes photos and garments showing the incredible range of looks and styles popularised during the nineties. The typical push-and pull between extravagance and a mannerist backlash is, it seems, no longer the operative mechanism of change. Most persuasive of this point, perhaps, are two photos from American Vogue: one featuring Naomi Campbell and Kristen McMenamy attired in McMenamy's signature grunge style from the December 1992 issue (catalogue commentary notes 'the extravagant perversity of casting one of the "It" girls of high fashion, Naomi Campbell, as a grunge-rock groupie'), the other posing anti-supermodel Moss with Campbell, both dressed in French Empire-style designs by John Galliano from the October 1996 issue. Stronger than any verbal commentary could be, these photos express that in every era, whatever the fashions, the greatest models have a quality that transcends time, place and circumstance. Upon leaving the exhibit, visitors might conclude with Koda and Yohannan that, while capable of embodying a time and a society, these women most convincingly embody themselves.

References

1. The Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion by Harold Koda and Kohle Yohannan, co-published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, is available in hardcover and paperback editions. The 224-page catalogue is fully illustrated with colour and black-and-white photographs and includes an exhibition checklist and selected bibliography.

2. Yohannan's monographs include Valentina: American Couture and the Cult of Celebrity (Rizzoli, 2009), Claire McCardell: Redefining Modernism (Abrams, 1998)and John Rawlings: 30 Years in Vogue (Arena Editions, 2001). An interview with Yohannan in which he discusses his role as curator of the Valentina show can be found on the Studio International website: Once Again, Fashion’s First ‘Beatnik’ Takes Centre Stage.

3. A physical recreation of the photo of Dovima at the Cirque d'Hiver opens The Model as Muse. The image, available as a postcard in the museum gift shop, is a memorable keepsake.