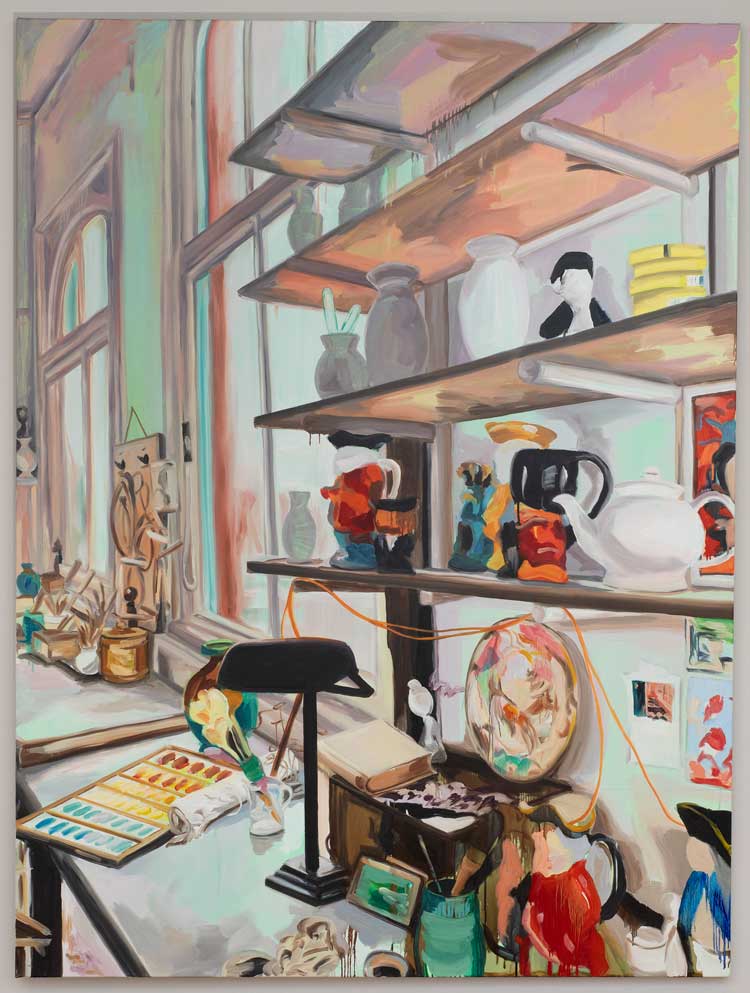

Anna Freeman Bentley, Make Believe, 2022. Installation view. Copyright Anna Freeman Bentley. Courtesy Frestonian Gallery.

Frestonian Gallery, London

21 September – 5 November 2022

by DAVID TRIGG

That cinema is built on an illusion is well understood, yet it is still jarring when films remind us of their fabricated nature. Take for instance when characters break the fourth wall by addressing the audience directly; an unconvincing piece of CGI; or when crew members and equipment are accidentally visible in a shot. Sometimes it is played for laughs, as in The Naked Gun (1988), in which Leslie Nielsen’s character walks around the edge of the set instead of using the door to move between rooms. But whenever conventions of representation are broken in this way, an audience’s awareness of the cinematic medium is momentarily heightened. Something similar happens in Anna Freeman Bentley’s compelling exhibition Make Believe, at Frestonian Gallery, where her sensuous paintings depicting empty film sets probe the boundaries between reality and illusion.

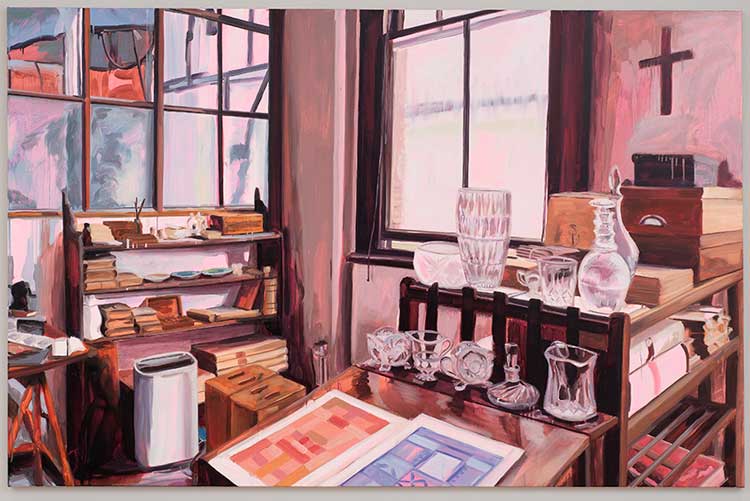

Anna Freeman Bentley, Painted wares, 2022. Oil on canvas, 144 x 222 cm. Copyright Anna Freeman Bentley, courtesy Frestonian Gallery.

During the latter stages of lockdown in 2021, Freeman Bentley undertook an informal residency on the set of The Colour Room (2021), a dramatisation of the early career of the prolific English ceramicist Clarice Cliff (1899-1972), the first female art director in the Staffordshire Potteries. As a painter of enigmatic interiors, Freeman Bentley was enticed by the film’s elaborate sets and the sense of place they conveyed. Recreating the production shops of the AJ Wilkinson factory in Stoke-on-Trent and rooms in Cliff’s family home, these temporary constructions, crammed with period objects, were designed to transport audiences to a bygone era. The resultant canvases and works on paper invite viewers into painterly interpretations of these mysterious scenes, which are at once real and unreal, solid yet ephemeral.

Anna Freeman Bentley, Knowing when to stop, 2021. Oil on canvas, 180 x 135 cm. Copyright Anna Freeman Bentley, courtesy Frestonian Gallery.

In the main gallery space are four large-scale canvases depicting different views of Cliff’s workspace, in which ceramic wares, books, brushes and jars of pigment fill shelves and workbenches. These confident, colour-saturated paintings echo the film’s vibrant chromatic palette with warm pinks, pastel peaches and minty greens. But they are not intended to illustrate any aspect of the film’s narrative, or, indeed, speak to Cliff’s biography. The absence of figures creates a sense of stillness, of anticipation, or even abandonment. As Thomas Marks suggests in his insightful essay in the accompanying publication: “The dressed and undressed sets become scenes of anticipation or aftermath.” At the heart of Freeman Bentley’s project, however, is a fascination with notions of artifice and illusion.

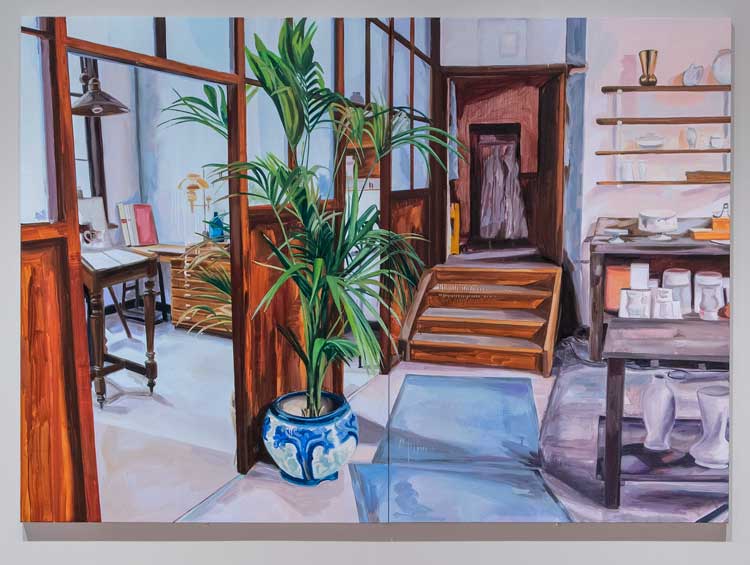

Anna Freeman Bentley, The Door to the Office Is Open, 2022. Oil on canvas, 135 x 205 cm. Copyright Anna Freeman Bentley, courtesy Frestonian Gallery.

This is underlined by the smaller works, Levels 1 and Levels 2, as well as a larger painting, Colour Mixing (all 2022), displayed in the gallery’s viewing room, all of which show backstage scenes and film-making equipment that were never intended to be seen on camera. By revealing the artificiality of the other images here, they cause us to question every detail: are the vintage objects we see in these paintings genuine or merely props? Is the light pouring through the windows real or artificial? And what lies beyond these sets: the real world, or more make-believe? In The Door to the Office Is Open (2022), a wooden cross hangs on the wall as a signifier of religious belief. Its presence, not unusual for the period, speaks to an era where faith in the unseen played a much bigger role in people’s lives than today. As Freeman Bentley says, her paintings are “powered by a fascination with what we do not see as well as what we see, in what things and places mean and signify and in an idea of longing for an elsewhere”.

Anna Freeman Bentley, Make Believe, 2022. Installation view. Copyright Anna Freeman Bentley. Courtesy Frestonian Gallery.

In all her paintings, Freeman Bentley embraces a photographic way of seeing. “I deliberately want my paintings to be inspired by a view through a lens with all the ways that a lens crops and contains a view by warping the angles and perspective,” she says. But though they create the illusion of space, there is nothing photorealistic about them; their status as paintings is ever before you. Drips, watery brushmarks and areas of gestural abstraction continually catch your eye: painterly passages that disrupt and question the solidity of what is represented. Like a cinematographer embracing lens flare as a creative effect, Freeman Bentley seems to relish this push and pull, which pervades all her painted spaces.

Anna Freeman Bentley, The Ticking Clock, 2022. Oil on canvas (diptych), 175 x 250 cm. Copyright Anna Freeman Bentley, courtesy Frestonian Gallery.

In The Ticking Clock (2022), a staircase painted with prominent brush strokes and trickles of thinned paint leads to an undefined, almost abstract space. To the left, through an open doorway, drips run down the wall, seemingly into a plan chest below. Elsewhere, in works such as The Door to the Office Is Open (2022), reflections in a grid of windowpanes become small abstractions – tempestuous clouds of pink, grey and blue marks. Where, these paintings ask, is the boundary between the real and the illusory? And are we able to distinguish artifice from authenticity in our own lives? Looking more closely at these works, we see the presence of incongruous objects: an air purifier, a coiled electrical cable, or a piece of modern lighting equipment, anachronisms that jolt us back to reality, where we remember that cinema’s ability to transport us to worlds beyond our own is only ever temporary.