Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

12 February–2 May 2005

[image1]

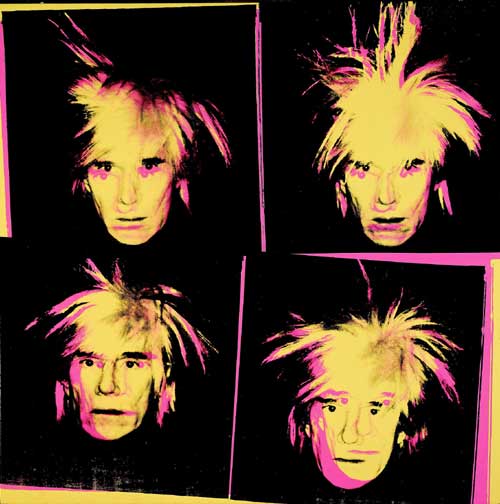

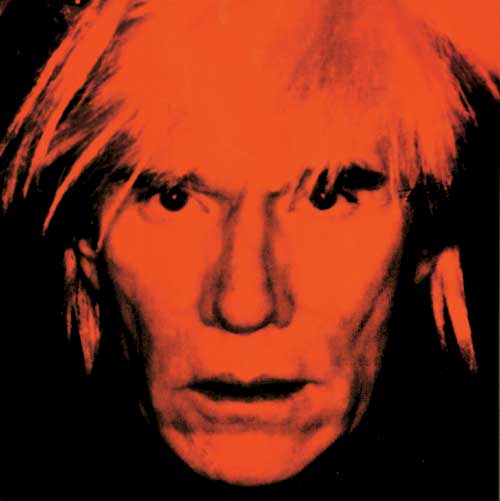

Every portrait in the exhibition projects both a vacancy and an allure, but essentially a superficiality that appears to betray no clear feeling. The artist's face drifts or stares blankly as if bored by the attention. In averting the gaze of the viewer, Warhol seems to deflect analysis and confrontation. He appears to say, 'Look at me, look at me! Stop staring, stop staring', both craving and scared of the attention. When he cast himself next to Hollywood's most famous, his own worth of celebrity was questioned - he had become well known by association with other famous people and by depending on the kindness of photogenic strangers. An actor out of place in the show, Andy's sketch was more in the tradition of Samuel Beckett than Hollywood. Part of the frustration induced by the self-portraits is their tendency to tease the audience in its attempt to understand Warhol:

We end up knowing everything and nothing. So it is that artists' self-portraits, whether intended as disclosure or as concealment, remain as fictional as their other work … Andy Warhol's self-portraits constantly shift back and forth between telling us all and telling us nothing about the artist, who can seem, even in the same work, both vulnerable and invulnerable, both superficial and profound.1

The viewer is waiting for the real Warhola, waiting for some insight, some depth, something more than the superficial. But the paintings do not, in fact, go anywhere; they do not show anything except a grey void behind dead eyes. Although the portraits were completed over a period of several decades, the expression hardly changes through the collection. There is no movement or vivacity beyond tension, no narrative and little communication, like a single frame in a film of a mime act, repeated many times.

Even when Warhol is at his most serious and confrontational, for example, in his series of portraits with skulls, there is an underlying black humour that dismisses any real sincerity. Connotations of Hamlet talking to Old Yoric's skull imply a theatrical prop and Warhol's earnest dialogue with his own mortality becomes another artificial play. Another painting of Warhol, wearing an exaggerated expression of horror as he is strangled, implies a B-grade horror film rather than anything more serious. And yet, to dismiss these explorations of mortality is perhaps to be too cynical. Warhol also painted guns, 'wanted' criminals and car crashes: his use of death as subject matter was not a passing whim, but a motif in all his work. It reflects his own near-death experience after he was shot three times by the deranged Valerie Solanas and pronounced clinically dead on the operating table. Although this subject is treated sardonically by Warhol in his film 'Andy Warhol TV', where he reflects upon the importance of good make-up in the coffin, the gravity of his expression, which is present in nearly all the portraits, suggests genuine fear and loneliness; but as a clown, he chose to paint it as a joke. He also turned Hollywood - through repetition of its symbols - into a theatre of the absurd and his own presence in the great parade turned it to parody:

'One of the standard devices of the art of clowning is endless and unbearable repetition. It serves as an excruciating illustration of the fate that condemns humanity to repeat itself - the same mistakes, the same recurring illusions borne of the same impossible dreams. Like Camus' Sisyphus, clowns express a condition of absurdity from which only awareness and feigned submission can offer any hope of emancipation.'2

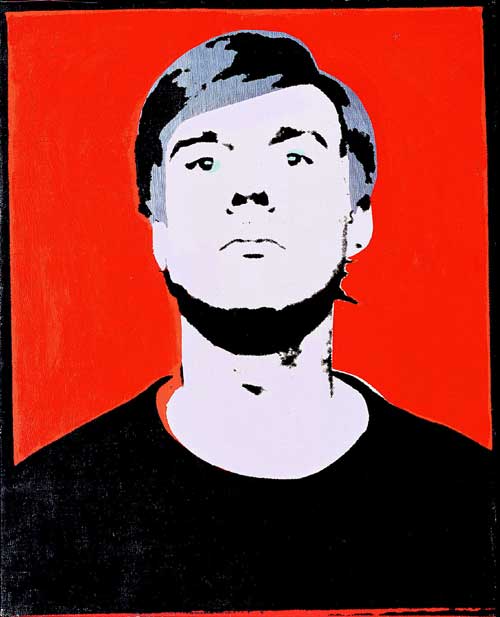

Warhol was aware of the absurdity of celebrity, of Hollywood and Western society, proven by his own place in it. He was both the prima donna and Pierrot of Pop Art, tragi-comic in essence. Only through his ability to ridicule the art world – by selling repetitions of soup cans and portraits of his masks, by avoiding the gaze of the viewer, by sending an actor incognito to lectures in place of himself and by giving monotonous 'yes', 'no' and 'I hadn't really thought about it' answers in interviews – could he gain liberation from the masquerade in which he was trapped. Only by acting like a clown could he be an artist.

A mask can have a number of uses: to scare, to entertain, to conceal, to deceive and to exaggerate. Warhol's self-portraits do all of these things; his works are an expansion of his masquerade and an insight into an artist who was a clown. Ultimately, in their vacancy, the self-portraits are not informative or insightful, but disarming. There is no person, no celebrated artiste, behind the masks any longer; only these portraits – the masks themselves – that will never fulfil the audience's curiosity towards an invisible man whose legacy was a collection of his own and others' masks. Warhol gives the viewer nothing more than the superficial, and the implications of absence. Here, there is no record of the actor, only the act. If Warhol was speaking the truth when he said, 'Just look at the surface of my films and my paintings and me, and there I am. There is nothing behind it', then he admits that behind his mysterious persona there was no substance, no meaning. Either the self-portraits are an accurate portrayal of a man who was nothing but a superficial construction, or a portrayal of a man who did not want to be seen as anything more than that; they are the invisible man's silver-grey hairpiece and dark glasses. He appears to have been dehumanised by his art, which often represented the nihilistic vacancy of society and celebrity. He came to epitomise his subject matter, or rather, the artist used the actor to represent the insubstantial masquerade that he became a part of.

In this collection of paintings, Andrew Warhola has not portrayed himself, but painted Andy Warhol, the star, the act, the mask. His self-portraits are a trick, teasing the audience with the implication of a man behind the mask. As Dostoevsky wrote in The Double, 'I put on a mask only for a masquerade.'3

Christiana SC Spens

References

1. Rosenblum R. Andy Warhol’s Disguises. 2005

2. The Circus of Cruelty: A Portrait of the Contemporary Clown as Sisyphus. In: Clair J (ed). The Great Parade. Yale University Press, 2004: 35.

3. Dostoevsky FM. The Double. Dover Publications, 1997.